An East German childhood: ‘People took off their clothes to express their freedom’

Published on

Translation by:

Sarah Pybus

Sarah Pybus

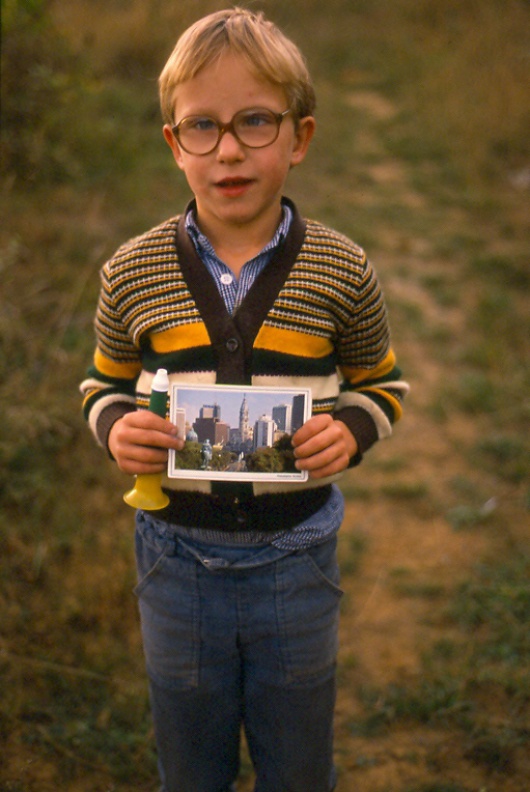

West Germans often subscribe to a pretty grim idea of life growing up behind the wall in the German Democratic Republic (GDR). Yet although East German children had few toys and less holidays, were they really less happy than their western counterparts? Eik, 29, recalls his Soviet upbringing

‘I was born in 1978 and spent my childhood in Penig, a small town in the southern part of East Germany. My father worked in a factory and my mother in a shop. We lived in a typical East German tower block like most ‘normal’ people at the time. I wasn’t particularly aware of the political system in which I lived. I only began to think about it in later years when I noticed just how different the socialist east was from the west.

‘I was born in 1978 and spent my childhood in Penig, a small town in the southern part of East Germany. My father worked in a factory and my mother in a shop. We lived in a typical East German tower block like most ‘normal’ people at the time. I wasn’t particularly aware of the political system in which I lived. I only began to think about it in later years when I noticed just how different the socialist east was from the west.

The pioneer movement

In the GDR, schools were not just educational institutions in the strictest sense of the word. In addition to normal lessons, ‘pioneer afternoons’ were organised based around different topics. These activities were designed to prepare us for our later role as ‘good socialist citizens’. I could hardly wait to become a member of the Free German Youth (Freie Deutsche Jugend, FDJ), but it never happened: the regime collapsed before I got my turn.

'I could hardly wait to become a member of the Free German Youth'

At school we also learnt how to interact with each other in a socialist manner, including the correct greeting. Each morning when the teacher entered the classroom, we had to stand. He shouted ‘Be ready!’ (‘Seid bereit’), to which we replied ‘Always ready!’ (‘Immer bereit!’). Only one of our teachers didn’t follow this rule: he greeted us with a simple ‘Good day’ (‘Guten Tag’). So we thought he was pretty cool.

Work and travel

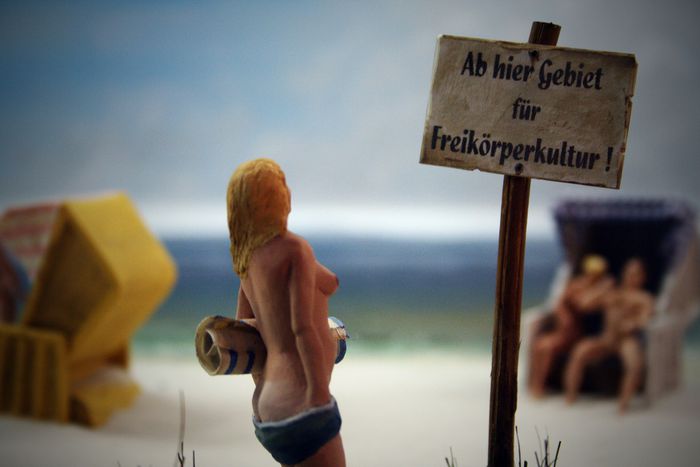

!['Be ready, always ready'; the motto of the socialist school system (Image: © [martin] / Flickr)](https://media.cafebabel.com/archives/6e/8e/6e8ee98b66ca41a73cc5cb4f6ff64029.jpg) People owned enterprises (Volkseigene Betriebe, VEB), ran sports associations and trips as well as organising holiday camps for the children of their employees. My family and I often travelled to the Czech Republic. One time we even managed to get to Hungary. More far-flung destinations seemed to be reserved for party members, who could then travel to the former Yugoslavia, Romania and Bulgaria. In a way, naturism was the East German response to the fact that they couldn’t travel freely: basically, people took off their clothes to express their freedom. A large part of the naturism tradition disappeared after the reunification, although nudist beaches can still be found in East Germany on the Baltic Sea.

People owned enterprises (Volkseigene Betriebe, VEB), ran sports associations and trips as well as organising holiday camps for the children of their employees. My family and I often travelled to the Czech Republic. One time we even managed to get to Hungary. More far-flung destinations seemed to be reserved for party members, who could then travel to the former Yugoslavia, Romania and Bulgaria. In a way, naturism was the East German response to the fact that they couldn’t travel freely: basically, people took off their clothes to express their freedom. A large part of the naturism tradition disappeared after the reunification, although nudist beaches can still be found in East Germany on the Baltic Sea.

The idea that East Germans knew nothing about West Germany is a myth. Even before 1989, most households could receive West German television channels. A great number of people did this – including my parents, although they were very careful not to talk about it to most people to avoid difficulties. East Germans knew, of course, that West Germans had bigger cars and nicer houses. But for all this, the west also suffered from unemployment and poverty. We didn’t experience any of these extremes.

The 'Wende', which led to reunification

In 1989 I was 11. The reunification of Germany coincided with other changes in my life. At first, the change in national politics caused no great disruption for me personally since the move from primary to secondary school was already changing my life in many ways. For me, political change merged with a natural progression from childhood to youth. The years that followed this magical moment are harder to describe. From 1989, East Germany aligned itself more and more with the West German standard of living. East Germans pursued material wealth with all their might. My family and I moved out of our grey tower block as soon as was feasible. Life was beginning anew.

In 1989 I was 11. The reunification of Germany coincided with other changes in my life. At first, the change in national politics caused no great disruption for me personally since the move from primary to secondary school was already changing my life in many ways. For me, political change merged with a natural progression from childhood to youth. The years that followed this magical moment are harder to describe. From 1989, East Germany aligned itself more and more with the West German standard of living. East Germans pursued material wealth with all their might. My family and I moved out of our grey tower block as soon as was feasible. Life was beginning anew.

Present and future

In socialist times, a job was for life. The turnaround practically shattered this certainty: job cuts had to be viewed as a consequence of progress. In recent times, however, East Germans who could not profit from the change have begun to call for a return to socialist values. Their nostalgia for the former East Germany goes so far that they ignore the negative aspects of the regime and emphasise solely the ideals that it partly managed to realise.

In socialist times, a job was for life. The turnaround practically shattered this certainty: job cuts had to be viewed as a consequence of progress. In recent times, however, East Germans who could not profit from the change have begun to call for a return to socialist values. Their nostalgia for the former East Germany goes so far that they ignore the negative aspects of the regime and emphasise solely the ideals that it partly managed to realise.

I concentrate more on the positive ways in which things have developed. I studied political science and have travelled through Europe – I’ve even lived abroad. I can choose between options that were never available to my parents. The system no longer decides how my life progresses, I do! I’m ready to seize the opportunities that my freedom affords me.’

Translated from Eine Kindheit in der DDR: Segen oder Fluch?