25 years of Solidarity

Published on

Translation by:

fiona wollensack

fiona wollensack

Strikes by Polish shipyard workers in Gdansk 25 years ago helped to usher in the end of the Cold War. But the Solidarnosc (Solidarity) trade union born out of the situation is today finding itself in a difficult position.

21 x TAK! – SOLIDARNOSC (21 x YES! – SOLIDARITY) stands emblazoned on a stone pillar at the entrance to the Gdansk shipyard. It was on 31 August 1980, following weeks of strikes, that all 21 demands made by the first independent trade union in communist Poland were met by the government. But what meaning does Solidarnosc, then led by Lech Walesa, have today for the men behind the gates?

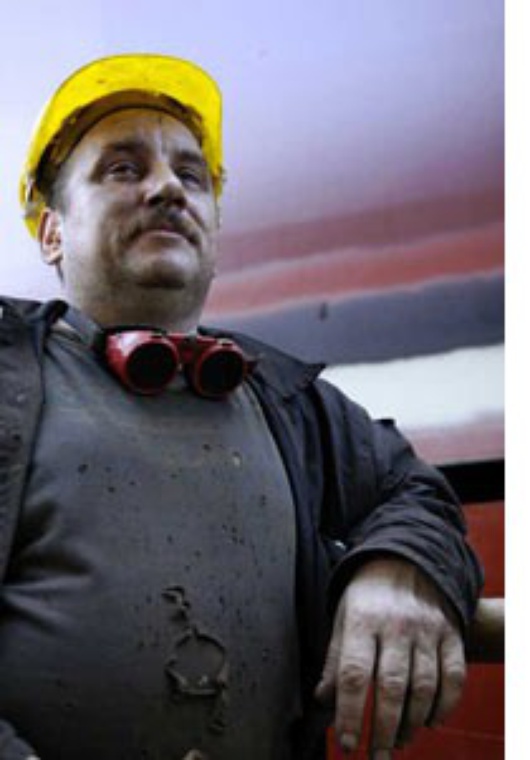

Mariusz Dolecki was three-years-old when the foundations of a democratic Poland were being laid. Now he and two colleagues stand in front of a ten metre high grey ship part, building a rig so that welding work can be done. He seems dejected, “The end is just around the corner for the shipyard and even Solidarnosc can’t change that.” It is true that following the innumerable restructurings, only 2,000 of the once 9,000 shipyard workers remain and nowadays only 5 or 7 ships are built per year.

Losing out after the Iron Curtain

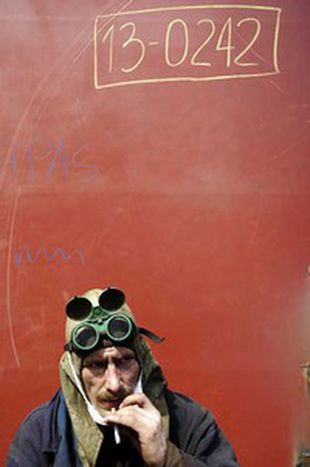

Solidarnosc is an integral part of the 57-year-old electrician Kazimierz Trawicki’s life. In 1970 he was part of the strike in the Lenin shipyard, during which peaceful demonstrators were shot down by tanks. Despite this experience, he became involved once again in 1980. “In 1980 we did not just fight for ourselves but for the whole of Poland”, Trawicki says with pride.

Solidarnosc is an integral part of the 57-year-old electrician Kazimierz Trawicki’s life. In 1970 he was part of the strike in the Lenin shipyard, during which peaceful demonstrators were shot down by tanks. Despite this experience, he became involved once again in 1980. “In 1980 we did not just fight for ourselves but for the whole of Poland”, Trawicki says with pride.

But the shipbuilders have become the first to loose out as part of Poland’s fledgling market economy. In 1996 the shipyard had to file for bankruptcy and was taken over by the Gdingener Shipyard Group as a subsidiary company. For many workers, Polish democracy is more closely associated with jobs-for-the-boys and exploitation than with an improved standard of living, the rule of law and freedom of expression. “Today everything is all about money”, says the union member Trawicki. “Unfortunately, our motto from the old days, ‘To be more, not just to have more’ has taken a back seat”.

Jumping over walls

The Gdansk strikes in August 1980 were triggered by the sacking of the crane driver Anna Walentynowicz. She had dared to demand better working conditions, such as a warm meal for the staff or heated production halls. Resistance to the sacking soon formed and, with his famous jump over the yard wall, Lech Walesa was able to place himself at the helm of the movement which swept Poland.

During a hard, 14-day struggle the strike leaders managed to push through 21 demands with the Polish government. The domino like fall of communist governments right through the countries of the Warsaw Pact began – never before had it been possible to achieve blessing for an independent union from those in power. Solidarnosc became the focal point of all domestic opposition and soon had 10 million of Poland’s 16 million workers as members. First the Polish President, General Wojciech Jaruzelski, negotiated, but by the end of 1981 he had forced Solidarnosc underground by invoking emergency powers.

During a hard, 14-day struggle the strike leaders managed to push through 21 demands with the Polish government. The domino like fall of communist governments right through the countries of the Warsaw Pact began – never before had it been possible to achieve blessing for an independent union from those in power. Solidarnosc became the focal point of all domestic opposition and soon had 10 million of Poland’s 16 million workers as members. First the Polish President, General Wojciech Jaruzelski, negotiated, but by the end of 1981 he had forced Solidarnosc underground by invoking emergency powers.

For nine years the activists had to wait until their efforts were rewarded with a place at the round table in Warsaw in 1989, at which their demand that socialism be changed into pluralist democracy was met. Lech Walesa was elected president of Poland and Solidarnosc joined the government. However, victory was short-lived as the group soon split itself into four groups and eventually lost all influence it had once had, the final straw being the electoral defeat of Lech Walesa in 1995.

Mythologising the movement

Today, the movement which is accredited with bringing about the fall of the Eastern Block is to be honoured with a museum – an ambitious project in which a new town covering some 73 hectares is to be built on the former shipyard of Gdansk. The museum will be at the entrance to the port city, and a portrait of Lech Walesa will smile down upon “Freedom Road” from the facade of the new museum.

This smile is meant to attract the money of investors, says Roman Sebastianski, marketing director of the investment fund Synergia 99. “The mythology of the Solidarnosc movement still sweeps down the streets here.” Up to 10,000 new jobs and flats for 6,000 people are to be created in the next 15 to 20 years in the new town, but the building project on the shipyard land is still controversial. For many people it is the final death knell for the shipyard, a fact they do not wish to have to face.

Will, after 25 years, the shipyard be buried along with Solidarnosc under its own larger than life mythology? This will be a hot topic of discussion at the celebratory events taking place during the coming weeks in Gdansk. The role of the man who became the symbol of Solidarnosc during its stellar rise will also be discussed, especially now that he, Lech Walesa, has now announced that he wishes to leave the union.

Translated from Solidarität als Museumsstück