Rwanda and the E.U : commemorating a genocide's divisive memory

Published on

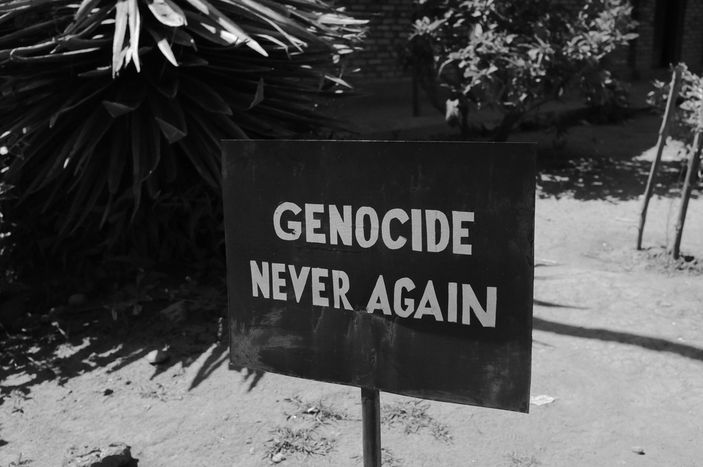

Events commemorating the 1994 rwandan genocide have been underway all over the planet for nearly a month now, and are scheduled to continue for the hundred days that the genocide lasted. Rwanda may seem a far-off land, but the legacy of the genocide has implications for Europe and europeans, as its shockwave continues to be felt.

“I understood that I hadn't understood anything”

On the 1st of April the Brussels Centre for Fine Arts (BOZAR) held the literary conference Rwanda, twenty years later. Three African writers who have written books about the terrifying 1994 Rwandan genocide were invited by BOZAR and the NGO “CEC” to speak about the limitations of language when applied to such an event. The answers were simple.

“I understood that I hadn't understood anything,” said Boubacar Boris Diop from Senegal, speaking of his experience in Rwanda four years after the large scale massacres that began in April 1994 and which killed over 800,000 Tutsis and moderate Hutus in just a hundred days. “I listened to people and couldn't understand”.

Véronique Tadjo from the Ivory Coast echoed something similar. “Some things cannot even be told, you have to express them in a different way”. That is why she, Diop and Rwandan writer and playwright Dorcy Rugamba have tried to write, in very different ways, about the genocide.

Rugamba, who lost many of his family in the killings says, “Memory is not faithful, it crumbles into pieces, we had to set it into place for it was an ideological, a political crime and that is the main thing to remember, it was not about ‘tribal’ or ‘ancestral’ hatred”. B.B. Diop agrees, “Genocidal logic is the logic of hatred, of mutilation”. All three say that fiction is a way of giving identity back to the dead . However, memory can prove to be something quite divisive.

« The dead are not dead »

This meeting was part of a wider trend of events that are designed not only to commemorate the genocide, but to heal the wounds of an African country mired in controversy. Projects such as “Upright men”, the product of the London-born South African artist Bruce Clarke, have been receiving attention at an international level of late, just recently the “Upright men” symbol was projected onto the facade of the United Nations in New York on the 7th of April.

Despite this the memory of what happened then is still a matter of controversy, even for some countries of the European Union. In France for example, a country repeatedly criticized both inside and outside of Africa for its role before and after the genocide, a court condemned Pascal Simbikangwa (a former captain of the Presidential Guard) to twenty-five years in jail on the 14th of March. Simbikwanga's trial was the first trial relating to crimes in the Rwandan-genocide to be held in France. It has made headlines because it is seen as a way for Paris to ease the tense relationship it has with Rwanda, whose ruling FPR party has often accused France of having protected officials from the genocidal Hutu regime.

This took place as both a French TV show and radio programme were forced to remove segments making fun of the Rwandan genocide under public and official pressure.

Aid, development and war

The memory of the genocide is at the heart of the European Union's relationship with the small African country. Public aid to development in Rwanda in 2006 amounted to 585 million USD, which made up for 24% of the gross national income and half of the government's budget. The European Commission was the second biggest aid giver in 2007, giving over 85 million dollars.

Rwanda makes a strong case for foreign aid: it has come back from the brink of destruction in 1994 to become one of Africa's numerous economic success stories; with its capital, Kigali, undergoing a real estate boom and the growth rate of the country being on average 8.1% per year between 2001 and 2012. Reconciliation has been one of the central official goals of new President Paul Kagame’s FPR regime. Ethnic censuses or mention of ethnicity on ID cards have been banned, however, some Rwandans still complain of discrimination. Even former Belgian Foreign Affairs Minister and former European Commissioner for Development and Humanitarian Aid Louis Michel declared his support for Kagame's regime in February: “I can only be impressed by the headway that has been made by Rwanda's economic and social successes”.

But some have accused president Kagame of authoritarianism and claim that Rwanda's FPR party is effectively in control of the country, leaving no room for others, and of using the memory of the genocide to shut down the opposition. The brutal murder of Patrick Karegeya, Kagame's estranged former Chief of External Intelligence, in South Africa on New Year's Eve has soured not only Rwanda's relationship with South Africa, but also with one of its main aid givers, the USA. It has been demonstrated in a 2012 UN report that Kagame financed rebellions in neighbouring Kivu, the mineral-wealthy eastern region of the Democratic Republic of Congo, whose natural wealth has continued to fuel one of the bloodiest wars since the end of World War II.

And in Brussels?

Even in Brussels the shockwave of what happens in central Africa can sometimes be acutely felt. The Matongé riots in 2011 are one such example, when Congolese expatriates, furious at what they saw as foreign-backed poll manipulations in the DRC presidential ballot, started demonstrating in the Ixelles neighbourhood. Possible cases of police brutality riled the demonstrators and sparked off two weeks of riots, in which some Rwandan people were targeted and much of the area around Chaussée d'Ixelles suffered considerable damage.

Despite taking place 6000km away from Brussels, the genocide of 1994 has had far reaching consequences; European Union involvement in a distant country, indirect stakes in a war that has shattered the whole eastern half of the DRC, French embarrassment and controversy, exacerbating the 2011 riots in Brussels, but most of all, it has broken more than lives, it has broken memories.

One of the writers invited to BOZAR, Dorcy Rugamba, recounts how he returned to Butare, his native town. “I went back to Butare, a place I know like my own shadow, but I didn't recognize it. It was full of unknown faces. Half the people had been killed, the other half had fled to Congo ».