Yuri Khashchevatsky: 'Being Belarusian is fashionable these days'

Published on

Translation by:

kate searle

kate searle

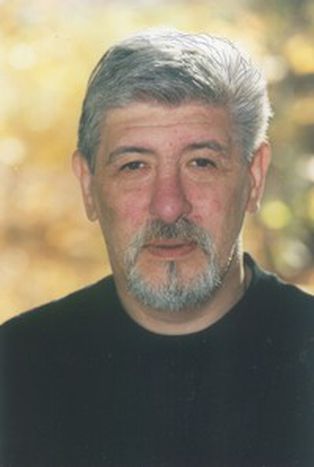

Visionary film director Yuri Khashchevatsky, 60, is a principal figure of Belarusian dissent. He criticises ineffective opposition, and talks up the new role the Internet plays in the resistance

’For the interview, come to my place, tube stop Lenin.’ Yuri Khashchevatsky, persona non grata as far as the Belarusian authorities are concerned, doesn’t particularly want to be hanging around in Minsk’s cafés. The director has just completed Ploscha ('Square', 2007), a documentary about March 2006, which saw a large part of Belarus’ youth demonstrate against the country’s president since 1994, Alexander Lukashenko, 52. He’s clearly in need of a bit of calm.

A year after the fraudulent re-election of the man even diplomats don’t hesitate to call ‘Europe’s last dictator’, the regime has got even harsher. ‘To the point where very few Belarussians are aware of the peaceful occupation of the October Square in Match 2006,’ remarks Khashchevatsky. ‘My film is only a drop in the ocean as regards to the waking up of Belarusians,’ says Khashchevatsky today. It's a drop of water which contributes to the rising tide of debate. Filmed using hidden cameras and edited using Windows '98, pirated DVD copies of Ploscha are circulating among Belarusians living all over Europe. Thousands of angry faces captured on film being lashed by snow and scattered by police batons. Is it a cinematic manifestation of a new revolution in the east?

Avid documentarian

Back to Minsk, the starting point. Off a dilapidated communal stairwell, the corridors of a long apartment, packed with books and the wooden floors untreated: in Khashchevatsky’s office a thin ray of light illuminates a muddle of books, dusty papers and an ancient computer. The master of the house has the false air of a Bukowski, his face barely visible behind a white beard, his eyes full of malice.

Born in Odessa in 1947 ‘to a Russian mother and a Jewish father,’ Khashchevatsky describes himself as a ‘free spirit’ and says that he’s been ‘pushing limits’ for years. He studied at the Technical College in his hometown of while dreaming of ‘becoming a theatre director.’ He worked for several years as a mechanic in Ukraine before moving to Minsk where, he says, ‘is his life’ - i.e., his wife and children. At 25, his determination paid off, and Khashchevatsky got a job writing screenplays for the state television. ‘I argued constantly with the director who was interpreting my texts,’ he remembers. Up until the point when the director, exasperated by his critics, proposed that Khashchevatsky film them himself.

His early work brought him visibility, and Khashchevatsky was sent to Leningrad to study at the prestigious national cinema and television institute. Twice a year he spent several months in Russia, fine-tuning directing techniques. He soon realised his preference for the documentary format. ‘You need less imagination than for a feature film because that requires you to create an interesting story around ordinary characters,’ he says. The country’s new leader Lukashenko didn’t appreciate his leading role in Khashchevatsky’s political satireAn Ordinary President (1996).

The film was featured at the Berlin film festival a year later, and earned Khashchevatsky six months in hospital following a visit by muscled employees of Minsk’s new master. Khashchevatsky is a member of Charter 97 (a Belarusian dissident organisation based on Charter 77 in the Czech Republic), and has continually publicly denounced the regime as ‘total contemporary totalitarianism.’

Placed under strict surveillance by his local KGB, he became more and more known for his work, frequenting international cinema festivals. Beatings and injuries then periods in prison alternated with shooting schedules. A member of the Eurasian television academy, he won the jury prize at the New York film festival for human rights for Prisoner of the Caucuses in 1998, his investigation into Chechnya. Today he has more than fifteen films and documentaries under his belt.

Idiots in opposition

’Dissidents were sent to psychiatric hospitals during the seventies in the USSR. Today we stuff the entire population with tranquilisers through the television or the state radio,’ he exclaims. So when will there be a new administration? An orange revolution in the mould of what happened in Ukraine is out of the question. ‘In Georgia and in Ukraine there were existing democratic institutions as well as the media and opposition parties. The people had a way in which they could take action.’ ‘Belarus,’ he continues, ‘is more like North Korea than Ukraine in this way. Here, people are imprisoned, killed, or at least they ‘disappear',' he explains, with an ironic wink.

Far from pushing for change, the various Belarusian opposition forces behave, in Khashchevatsky’s eyes, like ‘idiots’ mired in their divergences, who don’t move towards getting on. ‘Every one of them, including opposition candidate Alexander Milinkievitch, is a mini-Lukashenko who thinks he knows everything about everything.’ The sentence, said with affection, points the finger at the Belarusian dissidents who, brought up in the Soviet era, haven’t quite caught on to ‘delegation. They don’t understand that they have to work with professionals: lawyers, politicos, communication strategists,’ is Khashchevatsky’s analysis.

Nevertheless, ‘it is time to think up new ways of resisting,’ enthuses the director. Gone are the days of clandestine political tracts in letter boxes or newspapers distributed on the sly. The Belarusian opposition has a lot of ground to make up to stay virtual. ‘The ‘Samizdat’ (a system of self-publishing that allowed the distribution of dissident writings during the ex-USSR era), has been replaced by viral marketing,’ laughs Khashchevatsky. He believes in the potential of the Internet, and says the possibilities opened up by the web are ‘innumerable.’ He thinks the Belarussian youth are ‘perfect’ to exploit it.

‘Our young generation is strong, determined and mature. I’m amazed when I think about the strength that they need for this peaceful fight,’ he says. As for the emergence of Belarus’ elite, Khashchevatsky says they are promisingly ‘totally European.’ 'Being Belarussian has become fashionable these days. At least they are more effective than the ‘Brussels bureaucrats, who have no idea of the mess they make for the opposition when they correspond with Lukashenko.’ It is time that the European Union ‘found stronger arguments with regards to this presidential regime. Without which it will reveal its true lack of powerlessness.’

Translated from Yury Khashchavatski : « Etre Biélorusse est à la mode »