Yugo-nostalgia in Sarajevo: necrophiliac love for Che 'Tito' Guevara

Published on

Translation by:

ialeon‘Yugonostalgia’? Only the older generation can glorify the Yugoslav past, assures a Bosnian colleague. Yet in Sarajevo there is no doubt that the 1990s generation misses the communist leader Josip Broz Tito. Behind this idolisation of a figure that has long disappeared from the political arena is hidden a collective uncertainty for the future

‘Tito is our Che Guevara,' jokes Goran Behmen with a hint of embarrassment. The 36-year-old dons a chic style with a white button-down and sky blue tie. He is seated before a golden, unnaturally large bust of Josep Broz Tito, a dictator who led Yugoslavia from 1945 until his death in 1980. Goran is the face of the Tito association of Sarajevo, whose mission is to remind their country of the 'dictator’s positive qualities'. He reminds us that for example there was a higher level of security - you could sleep out the street all night without a worry - along with free access to culture and freedom of travel. This was all a reality in the former Yugoslavia.

Goran does not believe that Sarajevo's youth are nostalgic about Yugoslavia. For those born in the nineties Tito is more like a symbol. Goran, who is also the son of the mayor of Sarajevo, prefers to refer to Tito as a ‘socialist with a human face’. ‘He is seen as a hero. Tito is the biggest brand in Yugoslavia. As a dictator, he was different from those of Hungary, the GDR (German Democratic Republic), Czechoslovakia or Romania; he was not a dictator in the classical sense. He was more democratic. The typical strong kind of Balkan guy.' 30% of Bosnian youth agree with this vision.

We belong to Tito and Tito belongs to us

Aida, on the other hand, believes that Bosnian youth is not at all nostalgic for the times of Tito. She was only nine when the war (1991-1999) broke out. 'To be perfectly honest, we don’t give a damn,' explains the young woman, who is a part of the couchsurfing movement. ‘The only thing we care about is to make it in this system. We don’t remember the old system.’ But young people don’t need to remember the past in order to experience yugo-nostalgia. The parents’ generation often convey that life was more chilling when Tito was in power. An Ipsos study conducted in 2011 by the European Balkan fund, with two generations (born in 1971 and 1991) from former Yugoslav countries, show surprising results. The majority of people born after 1990 consider life during Tito’s Yugoslavia to be better that that of today. The only exceptions are Croatia and Kosovo. In Bosnia and Herzegovina, 47% of the generation born in 1991 is convinced that life today would be ‘better’ if Tito were still in power. 38.7% even think that life would be ‘much better’.

‘Young people in Sarajevo here can’t help but look to the past. The future is too painful, we don’t plan ahead for it'

It would be unheard of to visit Sarajevo and not see Tito somewhere. His portrait is displayed in branded hostels, in coffee shops, bars and even in most Bosnian living rooms. In bookstores, Tito’s biography, a real bestseller, shares space with that of Swedish football star Zlatan Ibrahimovic (born to Bosnian-Croat parents - ed) and a photo album of the Srebrenica massacre. Within a short distance of the university, young people eagerly sip Sarajewsko beers at 'Caffe Tito'. At the entrance, a banner hangs with the motto: ‘We belong to Tito and Tito belongs to us’. We can order red or white ‘Marshall’ wine. But the young people, lounging comfortably in the military-patterned cushions on a Friday afternoon, drink beer and smoke cigarettes under Carlsberg-brand umbrellas right next to the storage tanks in the garden. Inside the café, the walls are covered in photos: Tito’s meeting with Kennedy or Arafat, Tito at the sea, Tito windsurfing - Tito in all places and situations. ‘Young people in Sarajevo here can’t help but look to the past. The future is too painful, we don’t plan ahead for it,' explains Eveline Beens, a Dutch student who led a three-month long study on yugo-nostalgia in Saravejo in 2011. In her book The Future of Nostalgia, Svetlana Boym, a Harvard professor born in the USSR, makes the distinction between reflective nostalgia and restorative nostalgia. According to Eveline, the yugo-nostalgia felt by the younger generations in Bosnia is of a reflective nature. ‘They are indeed critical of the current situation in their country but without moving beyond criticism. There is no sign of them wanting to break off.'

Behind the counter at 'Caffé Tito', Edo mans the coffee machine. The 24-year-old studies politics in Sarajevo. During the week he works at Caffé Tito to finance his studies. He is not only a Tito fan, he considers him a legend. ‘Everyone loves him,' he says in perfect English. Edo sees a bleak future ahead of him. In order to go into politics in Bosnia he would have to pull some strings. Corruption is everywhere. ‘Our policies are not in the interest of people. Tito, however, was committed to brotherhood.' Tito’s fanclub is not exclusive to men, confirm Jasmina and Alica while at Balkan Express, a Yugoslav-style bar where you can browse publications from 1982 in their original format. ‘Yes,' answer the two women, both 21-year-old linguistics students. ‘Maybe Tito had a bit of a dictator side to him, but it worked.' The ‘naked island’ - the island where the torture of Tito’s opponents took place in Goli Otok - certainly represents a dark time in the history of their country. Yet they would rather have the ‘respect’ of Tito’s era back, than cope with their own 60% unemployment rate.

Necrophilia and yugo-nostalgia

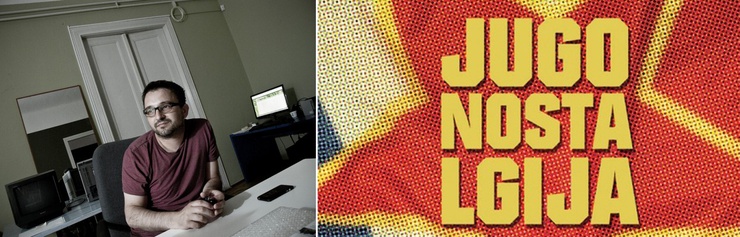

‘But if life was so grand at that time, why did everything collapse?’ asks a young Bosnian in Timur Makarevic’s documentary, JUGONOSTALGIJA, projected at the 2012 Sarajevo film festival. He finds trying to take advantage of the past as being almost akin to necrophilia. The JUGONOSTALGIJA director himself keeps his distance from the nostalgia. Timur says that television at the time was better than what it was today. However, the ‘yugo-pop-rock’ just doesn’t cut it for the 36-year-old. ‘I prefer Lady Gaga to Bijelo Dugme,' he laughs about the former Yugoslav rock band. He’s had many lively debates with his colleague, Mirza Ajnadzic, a young yugo-nostalgic who conducted research for the film.

In response, Mirza shakes his head. The 25-year-old journalist, who works for the local student radio station eFM, is convinced that 99% of young yugo-nostalgics would be in prison today. ‘They are just too liberal,' he says. While Mirza is a fan of block parties and the alternative music of the former Yugoslavia, he has dealt with yugo-nostalgia throughout his work on the film and has broken away from it for good. ‘Yugo-nostalgia doesn't actually exist. Young people are just longing for another political system. Titoism only exists because of this political situation. If you were to offer young people a new Yugoslavia, they would not want it. They would still want and need more. And that ‘more’ never existed in Yugoslavia.'

This article is part of cafebabel.com’s 2011-2012 feature focus on the Balkans, Orient Express Reporter 2, a project co-funded by the European Commission and with the support of Allianz Kulturstiftung. Many thanks to cafebabel Sarajevo; you can join the facebook group here

Images: main © Katharina Kloss; in-text © Alfredo Chiarappa, all for Orient Express Reporter II by cafebabel.com, Sarajevo 2012

Translated from Jugonostalgie in Sarajevo: Che 'Tito' Guevara und Nekrophilie