Young Europeans only know the Holocaust through war movies

Published on

Or do they? One of the most horrific events of the 20th century remains a painful recollection of a war spurred by false ideology that claimed six million lives. Nobody wants to take the trip down the road of oblivion, because it forces us to revisit the reality of humanity at its worst. Conversations in Spain and Italy

When I embark on interviewing people for this article, response is almost nil. 'It's just too depressing. Why talk about it?' is my Spanish husband's opinion. ‘It should be forgotten because a lot of innocent lives were claimed,’ adds Franco Monti, 35, from the northern village of Bertinoro, Italy. Silence is a common response from others. Do young Europeans refuse to engage and look at their own haunting past? A century later, will the Holocaust remain guarded in the corner of our psyche?

Media patrol

Media remains to be a powerful educational tool to ensure that the Holocaust is not buried with the times. 27-year-old communications and graphics professional Mattia Bergamini from Modigliana, northern Italy, describes how the media influenced his view of the Holocaust. ‘The meaning of the Holocaust comes from all the movies, books, speeches I've seen, read and heard.’ But you don’t need to experience the actual event in order to know the horrors of war. Mattia cites Italian writer Roberto Saviano who said that nobody can say that one has not been in Auschwitz, as was quoted in La Repubblica newspaper.

Media has played a central role in propagating false ideology during the Holocaust. It is important to listen to your conscience, Mattia says, than to people who say they want to make a better place. After all, his native country Italy for example, produced terrorists with an agenda of ‘making change’. How we will be able to prevent another Holocaust? ‘If we really want to understand what's going on around the world we have to ask ourselves why? and then points out to the necessity of solidifying Europe´s role in global politics. It is important that European countries become members of the international criminal court, but the absence of China, Russia and the United States will make the ICC less effective.’

World War II tour

Young Spanish-Filipina Kristine Salud had always been passionate about world war II. In her job as an business analyst for a major oil company, she has had the privilege of travelling to exotic places, but her interest in history urged her to take a trip that most people would just choose to skip. She embarked on a world war two 'tourism' tour with her cousin in 2006. Why Warsaw and Auschwitz of all holiday spots? 'It is an important part of history which I have always been fascinated with,’ she adds.

travelling to exotic places, but her interest in history urged her to take a trip that most people would just choose to skip. She embarked on a world war two 'tourism' tour with her cousin in 2006. Why Warsaw and Auschwitz of all holiday spots? 'It is an important part of history which I have always been fascinated with,’ she adds.

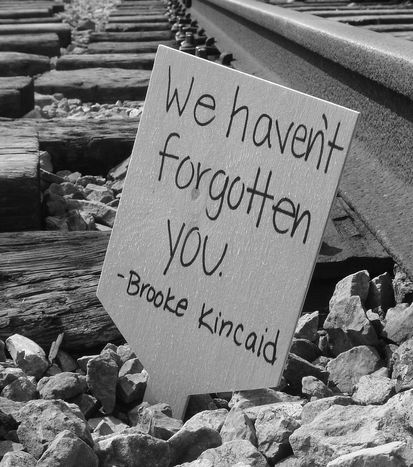

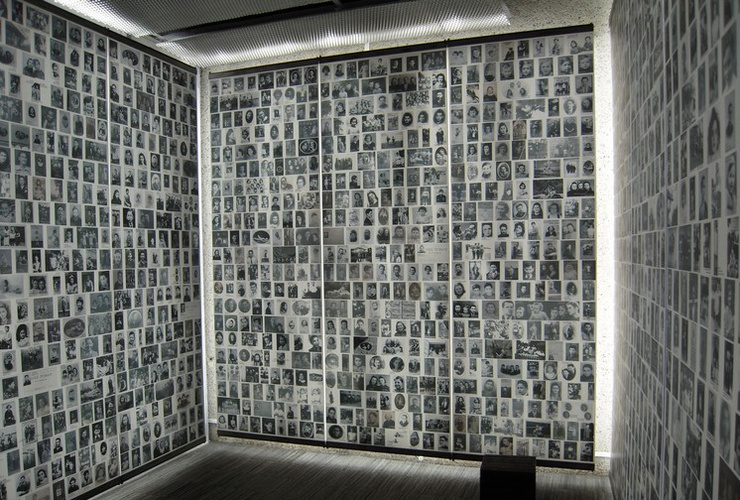

For Kristine, movies cannot match the actual experience of being there. Apart from the leather-worn suitcases, piled hair (from victims) and other 'memorabilia' which she saw in the now-converted museum of Auschwitz, Kristine could not forget the feeling she had of being inside what was once a concentration camp, where the ‘ghost of suffering’ is omnipresent. ‘It was like being inside a cave. It was cold. There was sadness all over the place,’ she recalls. She noted a lingering smell that triggered a memory of something damp and old, a smell that can probably best describe death. Recalling Anne Frank and how she and her family lived in a small cramped up attic for two years, Kristine explains that for her, the Holocaust ‘symbolises the death of innocent victims.’

Artist´s way

From movies to music; for 22-year old aspiring musician  Micael Rincon, the Holocaust is ‘one of the darkest, saddest and least-comprehensible chapters of mankind’s history.’ He has already penned some songs that touch upon themes of life and the metaphysics of death. He admits that the Holocaust has had some bearing on his perception of mortality, but emphasises that it has had even more impact on his ‘perception of life and responsibility.’

Micael Rincon, the Holocaust is ‘one of the darkest, saddest and least-comprehensible chapters of mankind’s history.’ He has already penned some songs that touch upon themes of life and the metaphysics of death. He admits that the Holocaust has had some bearing on his perception of mortality, but emphasises that it has had even more impact on his ‘perception of life and responsibility.’

Born to an Italian mother and a Spanish father, Micael spent most of his life in Switzerland, and his origins surely make him aware about respecting diversity. ‘(Because of the holocaust), I have to avoid or prevent any type of racism, classism, segregation and separation around me and in my own mind, whenever I can. It might sound utopian and preachy, but that’s how I feel about it.’ As an artist himself, Micael still believes in the healing power of music and art in times of tragedy. ‘It can play an uplifting message of hope in these cases. Often, in terms of clear information, art can be more trustful and honest than any kind of media.’ He points out how lucky we are compared to the six million victims who died in the death camps. ‘We are in paradise, just way too stupid to realise it.’