Yann Tiersen: ‘France denies its own cultures and smothers others’

Published on

Translation by:

Andrew Hetherington

Andrew Hetherington

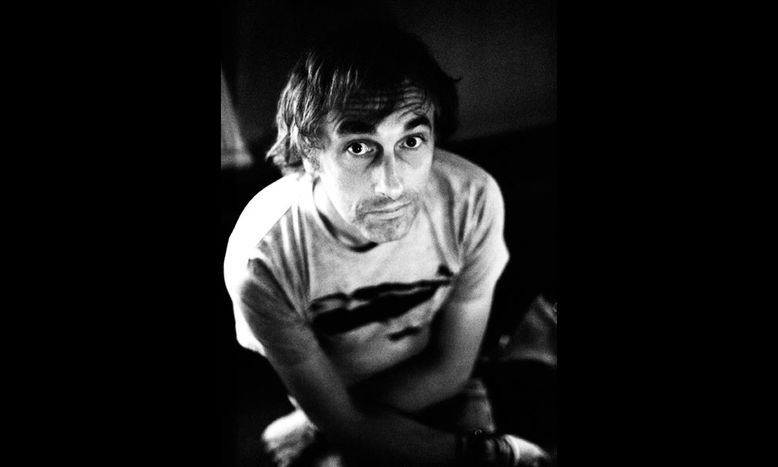

The Breton musician splits his time between touring and his ‘home’ of Ushant, a small island off the Finistère coast where he works alone on his albums. His slightly matted hair and earring give Yann the air of a sailor, one of those people who are quick to recognise the immense diversity of the world and leave their homes to understand it better

A light wooden staircase leads up to an airy room where hundreds of vinyl records cover the wall reaching the ceiling. Voltaire, a giant, spotlessly clean dog, greets me enthusiastically. ‘I’ve lived here since 2003,’ Yann Tiersen tells me as he is serving me a coffee. Barefoot in his den, cigarette drooping from his mouth, he crosses the room to put on an LP. A pair of rollerskates lie on the balcony where we sit down. ‘I have two kids, which is why I spend half of the year in Paris,’ he says, as the spellbinding music of the Icelandic band Múm fills the room.

Modern day bard

The Breton musician splits his time between touring and his ‘home’ of Ushant, a small island off the Finistère coast where he works alone on his albums. His slightly matted hair and earring give Yann the air of a sailor, one of those people who are quick to recognise the immense diversity of the world and leave their homes to understand it better. He has just returned from a tour of Iceland and the US, where most of his tours are at the moment; this last one was his fourth American tour in two-and-a-half years.

The Breton musician splits his time between touring and his ‘home’ of Ushant, a small island off the Finistère coast where he works alone on his albums. His slightly matted hair and earring give Yann the air of a sailor, one of those people who are quick to recognise the immense diversity of the world and leave their homes to understand it better. He has just returned from a tour of Iceland and the US, where most of his tours are at the moment; this last one was his fourth American tour in two-and-a-half years.

Read 'Yann Tiersen: not only about Amelie' on cafebabel.com

Tiersen is promoting his last two albums, Dust Lane and Skyline, which are more post-rock and hypnotic than the earlier ones. US audiences are apparently very enthusiastic, more so than in France, where Tiersen says he feels pigeon-holed by the music he wrote for the Amélie soundtrack in 2001. ‘That’s a problem here,’ he admits of his native country. ‘It isn’t like that elsewhere so I can live with it. It annoys me, although I don’t really know why. France isn’t a country with a strong musical culture. It’s not the case in Brittany (a region in north-western France - ed), which is a ‘normal country’, like the rest of Europe, where there is a much stronger musical tradition.’

Yann doesn’t feel that he has made a change in direction towards rock or electro. ‘I’ve evolved slowly through my albums,’ he says. ‘It isn’t really electro; we have an electro project but there isn’t yet an album.’ This project is called Elektronische Staubband, a German translation of ‘Dust Lane’. ‘After we returned from touring in 2011 an Italian promoter invited us to produce electronic versions of our last two albums. He knew we’d already dabbled in it, and that’s how the group started.

Far from France

Born in Brest, Tiersen grew up in nearby Rennes where he lived until the age of 22. Self-taught, he didn’t go to university and got his first taste of the world with rock bands. ‘I started making music on my own and worked a lot with samplers,’ he says. ‘But I got tired of working for hours in front of a screen. So I went back to playing unplugged. I held on to the idea of sampling but started doing it live with a microphone, for balance. Above all, instruments are tools to be used as things which make sounds. They can be objects, whatever.’

Born in Brest, Tiersen grew up in nearby Rennes where he lived until the age of 22. Self-taught, he didn’t go to university and got his first taste of the world with rock bands. ‘I started making music on my own and worked a lot with samplers,’ he says. ‘But I got tired of working for hours in front of a screen. So I went back to playing unplugged. I held on to the idea of sampling but started doing it live with a microphone, for balance. Above all, instruments are tools to be used as things which make sounds. They can be objects, whatever.’

In his most recent albums Tiersen has favoured the language of Shakespeare, which he finds more open and simple. ‘You can do a lot with English. It’s more precise because there are many more words. I find French too analytical, which doesn’t really lend itself to making music. There are wonderful things about the chanson française but that isn’t really what I listen to.’ The musician finds France too inward-looking, focused on an artificial idea of a francophone world. ‘While it’s a country with enormous wealth and diversity, there’s a kind of defence of the French language which is counterproductive. We smother other cultures on the grounds that we don’t want multiculturalism.’

This isn’t the case in Brittany, however, which has a language older than French and where Tiersen says the culture is more open to the world. He doesn’t claim to be a traditionalist or seek independence, as he emphasises: ‘France really denies its own cultures, like that in the Basque Country or Corsica. However they are our economic future. Whatever perspective you take, whether anti-globalisation or pro-single European market, the future is all about Europe’s economic and cultural regions rather that its larger nation states.’ His most recent albums reflect this new world view and are full of images of travel and exploration, far-removed from French nationalism. Describing his music in analytical terms is useless. Listening is enough.

Images : © Natalie Curtis; in-text : (cc) mairaeiou/ flickr ; album cover © courtesy of Mute Records/ videos : themutechannel/ youtube

Translated from Yann Tiersen : « La France nie vachement ses cultures »