Why young Poles are choosing to stay and work in Poland

Published on

Translation by:

Ceris AstonGone is the time when Poles thought of leaving their country to find work abroad. Nearly ten years after Poland entered the European union in 2004, young people from Warsaw wish to actively participate in the development of their capital

April 2013. Between the mismatched buildings of the grey city, piles of snow provide a bitter reminder of the harshness of the previous winter. Nonetheless, life in Warsaw goes on. Not far from the colourful historic centre, which was rebuilt identically after its destruction in the second world war, we find one of the main arteries of the town. New World Street (Ulica Nowy Swiat), which is lined with coffee shops and bars, is also home to the university of Warsaw.

Camping, sunshine and working for peanuts

At the 'Ministry of Coffee', Kamila Baranowska discusses the difficulties faced by earlier generations, but also her own. The tiny 24-year-old is slight but energetic. She spent a semester in Rome as part of the erasmus European student exchange programme. Kamila is passionate about travelling and has worked elsewhere in Europe during her summer holidays. Her favourite place, Greece, may seem an unrealistic destination today, with an unemployment rate that has reached 64.2% amongst under-25s. Whatever the case, it’s easy to understand why young Polish people leave their country for a month or two when one considers the pay practices at home. As a waitress, Kamila found herself earning only 7 zlotys per hour, or 1.68€. This amounted to a meagre pittance at the end of the month - less than 340 euros. By heading to the Greek coast to work she easily made double that. 'The sun and scenery were a bonus,’ she smiles, her eyes sparkling.

It was this same reason that led Pieter Wogcik into exile for two years in a row during the summer season. He left with several of his friends for the Netherlands, where they worked in the fields harvesting tulip bulbs. He worked ten hours a day, five days a week – six if he wanted to. Surrounding him in the fields were only Polish and Turkish people. The work was very physical and exhausting. In that first year, Pieter discovered all the joys of camping, holidays spent with friends, Amsterdam, independence, and, in his words ‘the land of the free’. He describes his Dutch employer as a friendly man who did not seem to wish to exploit his workers. The salary was determined upon the basis of age. For young people over twenty years old it varied between 6€ and 7.75€ per hour. Pieter explains that the hourly rate corresponded with the maximum that an experienced Polish worker who was moonlighting would receive. One year later, Pieter returned to work in northern Europe, but this time became swiftly disillusioned. He speaks of dull days, full of repetitive, cumbersome tasks, boredom and exhaustion. The young man – a student of the psychology of work – discovered the reality of life behind the scenes. Today, he says he’d rather apply his knowledge than his physical prowess at work.

EU doors opened

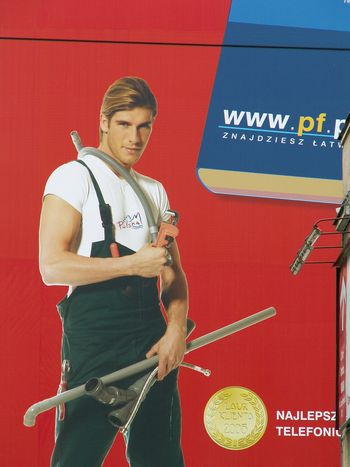

We are far from the myth of the Polish plumber – or nurse – which sprang into being in 2005, particularly in France, during the debate on the Bolkenstein directive. At that time, there was a widespread fear in mainland France that immigrants from Eastern Europe would flood in and take their jobs by working for a salary a third of the size. There had been a wave of immigration when Poland entered the European union in 2004, but in fact Polish people emigrated mostly to the United Kingdom. The reality for young Polish workers is that Europe is unlikely to welcome them with open arms, and certainly not for employment deemed 'intellectual'.

If since 2008 the financial crisis has plunged many EU countries into economic and social misery, conversely, Poland has come out of it. ‘We went from 4.5% to 1.7% growth in recent years,' says Monika Constant, the director of the French chamber of industry and commerce in Poland (CCI). 'While this is slow, compared to other countries in Europe we’re doing well.' Poland has managed to keep its economy afloat and has become increasingly dynamic. Although 650 to 700 French companies are located in Poland, it is Germany that has become the leading investor. The two countries make frequent exchanges. At present, Germany is home to 176, 000 Polish immigrants. Certainly, there are good prospects for further growth. However, Monika Constant also speaks of Warsaw as ‘a springboard to neighbouring countries’ such as Ukraine and Russia.

Moreover, even if 75% of Polish exports go to the economically weak European union, internal demand within Poland remains strong. With its 38 million inhabitants, Poland has been able to get through the crisis in a less painful fashion than many countries. However, the director of the CCI puts things into perspective. The return of a large number of emigrants who had been living in England, Ireland and France has led to an increase in the rate of unemployment in Poland. Recent European statistics put the number of unemployed at 10%.

One point is emphasised by the various interlocutors: Warsaw is quite different from rural areas of Poland. For Monika Constant, if young people decide to stay, it is perhaps because they are aware that there are opportunities to find jobs in the heart of the Polish capital. As for the young people of Warsaw, they stress the quality of the education that they have received. Utopia or not, they wish to pursue careers in the city where they grew up. Though they’ll happily travel abroad for an erasmus year, internships or summer work, the idea of emigration does not possess the same allure for this generation of Poles as it did for their parents. Yet, as Pieter points out: ‘We can never say never.'

One point is emphasised by the various interlocutors: Warsaw is quite different from rural areas of Poland. For Monika Constant, if young people decide to stay, it is perhaps because they are aware that there are opportunities to find jobs in the heart of the Polish capital. As for the young people of Warsaw, they stress the quality of the education that they have received. Utopia or not, they wish to pursue careers in the city where they grew up. Though they’ll happily travel abroad for an erasmus year, internships or summer work, the idea of emigration does not possess the same allure for this generation of Poles as it did for their parents. Yet, as Pieter points out: ‘We can never say never.'

Follow the cafebabel Warsaw blog here

This article is part of a series of special monthly city editions on ‘EUtopia on the ground’; with reports ‘dreaming of a better Europe’ from Budapest, Athens, Warsaw, Naples, Dublin, Zagreb and Helsinki. This project is funded with support from the European commission via the French ministry of foreign affairs, the Hippocrène foundation and the Charles Léopold Mayer foundation for the progress of humankind

Translated from Le plombier polonais n’est plus dans les tuyaux