Why the ‘’Indignados’’ Movement is Not Happening in Belgium

Published on

By Pauline Michel Translated by Danica Jorden

The ‘’Indignados’’ movement, first started 15 May in Madrid’s Puerta del Sol, has not ceased to grow in the countries of Southern Europe. It has become very popular in Portugal, Spain, Greece and Italy. However, it has hardly taken off in France, Germany or our country of Belgium.

On 15 October, movement protests were held here and there around the world, but with differing levels of participation. For example, 600,000 people were counted in Barcelona, but only 35,000 in Paris. It was the same story on 11 November, the second worldwide ‘’Indignados’’ day of protest. Generally, the level of indignation is highest where the effects of the economic crisis are being felt the most, but especially where leftist governments already in power have not been able to respond to the urgent questions the crisis poses.

Movement Not Going Anywhere in Belgium

In Brussels, between 3,000 and 7,000 people came out on the streets for the second day of worldwide ‘’Indignados’’ protest, according to sources. It was a modest mobilisation when one takes into account the number of foreign ‘’indignados’’ who came to the European capital for the protest. Different explanations can be made. Firstly, the Belgian political situation, which after long months of blockage, finally seems to be resolving itself, has proven that democracy works, even thought it takes time, patience and compromise. Another point is that it was the Socialist Party that partially opened the way for negotiations, whereas in other countries – especially in Spain and Greece – the Left hasn’t been able to fulfill its role in the crisis and has been in some ways discredited. It won’t be an accident if the day after the 20 November elections, all of Spain’s press puts the Right largely in power in Madrid. Thirdly, while the social situation is less than idyllic in Belgium, it is still far better than in Spain. In September 2011, the unemployment rate for Belgium’s active population rose to 6.7%, whereas it was 22.6% in Spain. If the unemployment rate rises to 17.4% for the under-25 group in Belgium, it will still be 48% in Zapatero’s Spain, and 43.5% in Greece. The Belgian social system, one of the best performing in the world, has protected its citizens as well, if not better, than most against the ill effects of the crisis. Unemployment, family and CPAS (public social action centres, available in every municipality) benefits, mutuals and even salary adjustments are unique social barriers limiting social unrest.

Belgium as Initiator of Social Dialogue

Like the social protection measures, labour unions and political parties have very deep roots in Belgian history. The country was built upon these pillars, and labour unions have mobilised a large part of the population since their inception. Given the history of the country’s economy, with its long-time industrial foundations, the living conditions of workers – and others – have rapidly become problematic. To ease these problems, and to prevent the movement and its strikes from impeding constructive and financial development, social dialogue has become a recognised mechanism. Even today, means such as joint commissions, union delegations, and interprofessional commissions are weapons in the fight against workers’ precarious situation. That’s why even today, the support of unions for social demands limits the influence that social movements like the ‘’indignados’’ could have.

The Belgian Camp Episode

Another explanation for the lack of attraction to the movement is the Belgian camp episode. The week before the 15 October protest, Philippe Privin (MR) Koegelberg’s mayor, authorised the protestors to occupy the ground floor of the recently emptied University of Brussel’s College (the HUB). At the end of the week, the building was returned in a lamentable state to authorities, with graffiti tags on all eight floors, excrement, a ravaged library and all kinds of disrespect not in keeping with the movement’s professed pacifist and positive ideas. This episode did very little to service the image of the movement in Belgium.

A Strategic Error

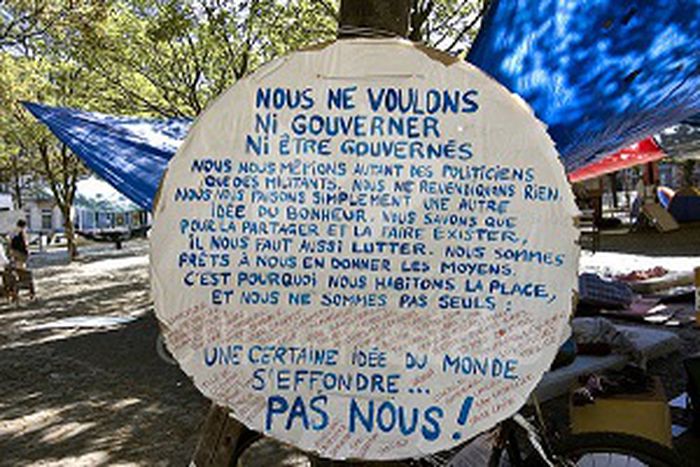

The reasons brought up for the lack of involvement in the movement in Belgium also apply largely to France and Germany. But one of the most plausible explanations resides in the lack of coherence in the movement’s demands. They are so flexible and unofficial that it is hard to see where the movement wants to go with them. In Spain, the ‘’indignados’’ are demanding employment, in Greece hope, housing in Israel, and in the U.S., a lessening of the financial sector’s monopoly on politics and society. The protesters are having a hard time speaking in a single voice, they are not visible and thus are having difficulty being heard. They claim to represent all facets of society, whereas a study shows that they are largely from the Left. By refusing to be a part of the political system, they make themselves less credible. How can a movement with a leader, image or demands be taken seriously? The protesters are criticising present society without presenting an alternative.