Why do we prioritise some tragedies more than others ?

Published on

2015 has hit us with some shocking attacks by Islamic State (IS) and all of its affiliates. Some have had a profound impact on us, and others less so.

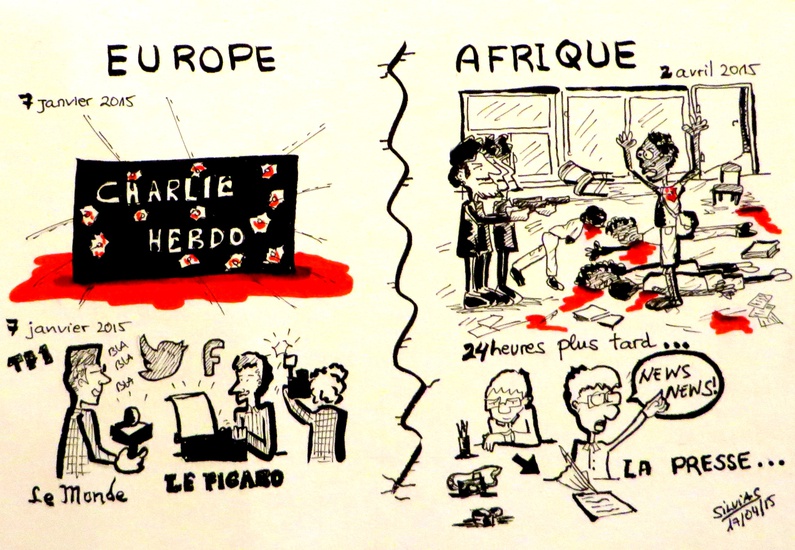

The latest of these horrors took place in Kenya’s Garissa University College at the beginning of this month. Yet this time, the news was revealed by the press almost 24 hours later. Not before.

When the tragedies of Charlie Hebdo and the Bardo National Museum happened, we were informed almost immediately. Under the same pretext of religious fundamentalism, almost 150 students were slaughtered in Kenya, yet we do not seem to identify with this story as much. Why do we react so inconsistently to human tragedies ?

January 7th : two terrorists burst into the Charlie Hebdo Offices in Paris and murder 12 people, of which many were senior members of the magazine. Soon after, social media channels and news coverage go into overdrive. Thousands of people from all possible known sources of communications express their shock and solidarity. ‘Je Suis Charlie’ profile pictures, peace rallies in pretty much every European capital, political leaders uniting for free speech (including six African presidents), etc.

We witnessed something similar again on the 18th of March, although on a smaller scale. Three terrorists tied to IS storm inside the Bardo National Museum in Tunisia, killing 23 tourists, of which most of them were Western.

April 2nd : A group of radicals tied to Al Shabaab kill 147 students from the University of Garissa in Kenya. But before, they carefully separate the Muslims from the Christian students, enclosing these in a confined space where they could easily massacre them and cause a blood bath.

Yet this tragedy only seemed to produce an echo in Western media and society. This time there were no world leaders, no peace rallies, and nowhere near the shock. The only memorial I could see shared on social media were the gruesome images of slaughtered bodies spread across the floor of one of the campus buildings.

Just imagine what would have happened if 150 students were killed in a European university campus, would we be so elusive to the point we dehumanised tragedies?

A few years ago, a very interesting article called ‘A hierarchy of death’ explained the reasons behind why we react more to some tragedies than others: proximity and the quality of information.

A few years ago, a very interesting article called ‘A hierarchy of death’ explained the reasons behind why we react more to some tragedies than others: proximity and the quality of information.

1. Proximity

The first one is pretty straightforward. We tend to show more interest and relate more to information that is near us. Logically, when something happens in our country or neighbouring countries we tend to give it more attention than if it were in places far away, or in countries with different cultures and a societies we can’t relate to.

2. The quality of information

As soon as something happens in a Western country, the media quickly deploys its special envoys and correspondents to cover the story, providing an unlimited flow of information. But in countries such as Kenya, Nigeria and Syria - or even more recently, the earthquake in Nepal - where the danger is much higher and the resources much scarcer, it is much harder to get ‘on the ground’ coverage.

It is not the lack of trying of course, as often journalists are restricted to a confined and secured space, receiving only filtered information. Proximity and quality of information certainly have a weighted influence on us talking more about Charlie Hebdo than Garissa University. But it should by no means be a reason to prioritise tragedies.

Many have a preconceived image of Africa as war-torn continent stricken with hunger, misery and violence. Many believe that all of it is so distant to our reality that it won’t come back to haunt us, but terrorism is a global reality. By dehumanising a tragedy because of race and/or religion we are only doing a favour to Al Shabaab, IS and Boko Haram.

In a globalised world, everything and everyone is intrinsically linked and connected in some way or another. It might be time to stop thinking that someone on the other side of the world is not our neighbour. These are global issues, whether they happen in Paris, Tunis, or Garissa.