Who Wants the Euro?

Published on

Written by Andrei Tuch

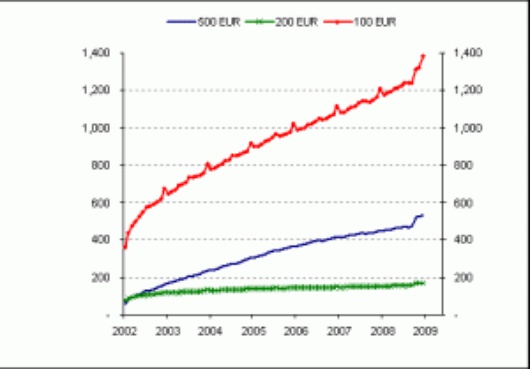

So, the world is in crisis, and the European economy is feeling rather poorly. The Eurozone states have run up huge public debt, and they’re barely managing to pay interest on it. Conventional economic theory suggests that there are only two ways to pay back the principal of such an overwhelming burden: savings during boom years, or devaluation.

Since they spent the good years borrowing, it’s unlikely they will do anything else once this crisis is over. On the other hand, the ECB has been printing Euros all through the crisis, and there’s no suggestion of them stopping. Meanwhile the Maastricht criteria for accession to the Eurozone are strict enough that any prospective applicant will have to have been quite prudent with their national finances.

The question is: shouldn’t the more developed member states keep their currency, so as not to be dragged down by the Euro’s troubles?

The answer is: No. But not because the national currencies are strong; rather, exactly because the Euro is weak.

The prospect of the Euro devaluing against a national currency is only a concern for countries with the sort of financial discipline and overall stability that lets them keep up the value of their own money; if both currencies get devalued, it doesn’t really matter. (For the purpose of the argument, let’s ignore the fact that devaluation will almost certainly mean the kind of inflation that puts the applicant outside the Maastricht criteria.)

Devaluing a national currency makes exports cheaper, but imports more expensive, so most people can only afford local products. The idea is that this builds up a base of manufacturing facilities and capable workers, as well as attracting foreign investment. But for devaluation to be a useful solution to an economic crisis, you need to be able to feed yourself. If your own agriculture and industry can support your population, then it will suddenly get a reliable set of buyers (they won’t turn to imported products), so you can make long-term plans, invest in equipment and training, etc. The fact that public debt is then easily paid off is an excellent bonus - but if you devalue without being able to sustain yourself until your economy is once again strong enough for imports to be affordable, the country as a whole is not going to get any use out of crashing the currency.

Devaluing a national currency makes exports cheaper, but imports more expensive, so most people can only afford local products. The idea is that this builds up a base of manufacturing facilities and capable workers, as well as attracting foreign investment. But for devaluation to be a useful solution to an economic crisis, you need to be able to feed yourself. If your own agriculture and industry can support your population, then it will suddenly get a reliable set of buyers (they won’t turn to imported products), so you can make long-term plans, invest in equipment and training, etc. The fact that public debt is then easily paid off is an excellent bonus - but if you devalue without being able to sustain yourself until your economy is once again strong enough for imports to be affordable, the country as a whole is not going to get any use out of crashing the currency.

And for the new member states, standing alone is unlikely to have any benefit either. Because we’re all in this together, the entire European Union, for better or worse. Every country that has made a decision to join, did it because it wanted to pull itself up to the European living standard. The successful ones did it not just through infrastructure subsidies, but through attracting investment from Western Europe: we made ourselves part of the European market. We may use our own currencies to pay for groceries, but the companies we work for sell their product for Euros. These days, in IT and other industries where keeping qualified employees happy is important, you will often see salaries established in Euros, or a contract clause saying that if the national currency gets unpegged from the Euro, your wages are automatically adjusted at the new rate. The difference between the Common Market and the Eurozone is increasingly academic.

Ultimately we come back to “strength in numbers”. If the economic crisis really is going to devour us all, and if the spine of the EU is cracking under the burden of massive public debt, then staying out of the Eurozone will not help member states avoid disaster. Forget about direct investment; revenue - even payroll - is going to dry up. Even in the worst case scenario, we will be far better off as part of an isolated, devalued, hyperinflated market of nearly half a billion consumers, than a clever and prudent loner.

Ultimately we come back to “strength in numbers”. If the economic crisis really is going to devour us all, and if the spine of the EU is cracking under the burden of massive public debt, then staying out of the Eurozone will not help member states avoid disaster. Forget about direct investment; revenue - even payroll - is going to dry up. Even in the worst case scenario, we will be far better off as part of an isolated, devalued, hyperinflated market of nearly half a billion consumers, than a clever and prudent loner.

The global economic crisis is showing us that there really is no such thing as “too big to fail”. But ironically,we would rather fail together than fall alone.