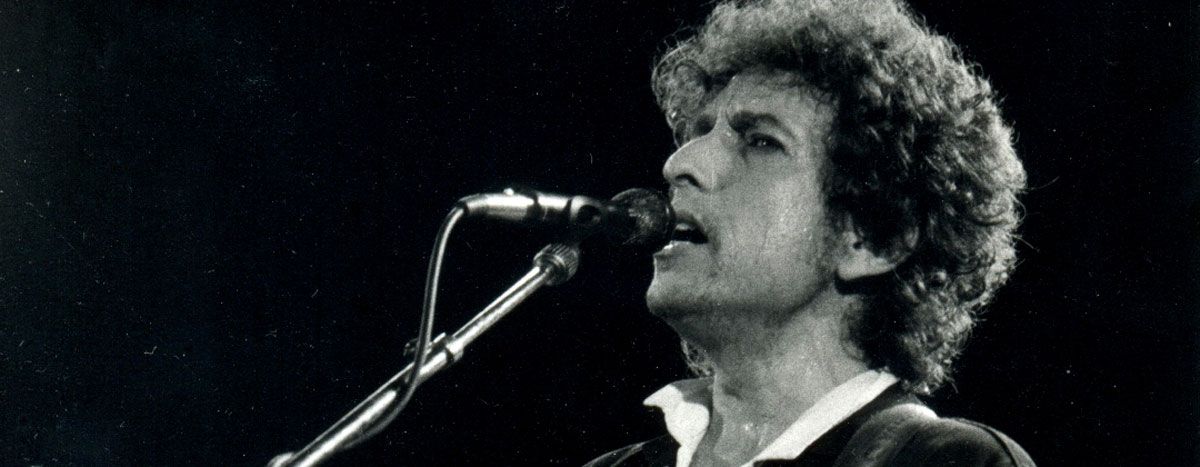

Where is our generation's Bob Dylan?

Published on

We look back at this year with a global face-palm and a universal sigh of exasperation. Instead of singing about reform and revolution, our generation has chosen memes and parodies as a coping mechanism. Why are we moving farther away from traditional protest music? [OPINION]

2016 has seen the deaths of Prince, David Bowie and Leonard Cohen, each of whom made their eminent mark in the world of music. We also saw the Nobel Prize of Literature awarded to Bob Dylan for his lyrical genius and influence. Even though their music dominated the charts in the late 60s and 70s, our generation still latches on to these musical icons for inspiration.

Protest songs and political music were the Yang of the 60’s Yin. Countercultural uprisings decorated the world through what seemed to be one common voice. Civil rights, anti-war sentiments and feminism became the world’s rhetoric.

In 2016 the world became characterized by strong political instability, ubiquitous terrorist attacks, and a struggle from the bottom-up to hold on to rights that were supposed to be set in stone. So if history tells us that the world can find a common voice in music to overcome struggles, where is our generation’s Bob Dylan?

As a teen, my dissatisfaction with the world, my elders, and the patriarchy in general was best expressed through music that wasn’t even of my generation. It belonged to that of my parents. I could relate to Buffalo Springfield’s For What It’s Worth, The Clash’s cover of Police and Thieves and Bob Dylan’s Subterranean Homesick Blues, but had nothing in common with Shakira, Pitbull or Jason Derulo. And although I admit that I felt intrigued by Eminem and his portrayal of white America, and felt empowered by the way Lil’ Kim openly rapped about female sexuality and demystified the clitoris, I found their music lacking in universality – the ability to transcend borders. Although 2016 (and our generation in general) has witnessed forms of political music, it seems to be less effective than it used to be.

Even though M.I.A.’s Borders was released in late 2015, its theme was an extremely pertinent topic in 2016: the European migrant crisis. Perhaps I am naïve in trying to draw comparisons between this song and those I mentioned earlier, but it’s a good way of demonstrating how blurry our definition of political music has become. The song has a catchy beat and M.I.A. repeats the phrase “what’s up with that?” to point out the malaises of our society today in regard to “politics,” “identities,” and even “the realness.” I respect M.I.A. and her active involvement in raising awareness of migratory issues, but when I separate the artist from the art, all I am left with is some overly simplistic lyrics and a catchy beat.

Our relationship to political music has undoubtedly changed. Whether that is for better or worse is difficult to say, given that new forms of media seem to dominate our means of expressing discontent. Naturally, the introduction of streaming and channels like Spotify and Youtube overpowered our relationship to radio. This could be one of the reasons we lost touch with the universality of protest songs. But we also saw the rise of social media, and with it came the outpour of parody songs and memes. Rather than addressing more global, social movements, we tend to hand-pick ‘fast news’ and race to find the best way to mock questionable politics. We don’t sing about reform, we laugh about how shitty the world is.

What’s sad to see is that in a year of global clusterfucks, I still have to listen to Bob Dylan to feel a sense of unity and find motivation for revolution and reform. I still hold on to Jimi Hendrix’s famous quote: “When the power of love overcomes the love of power, the world will know peace.”

2016: worst year ever. And all we did was complain.

---