When does design (not) become art?

Published on

Translation by:

Hanna SankowskaThere was no clear answer at the 14th pavilion of arts and design in Paris between 24 - 28 March. We talked limited edition pieces, the concept of twenty-first century art and the nature of spending at the internationally renowned trade show, which was held in the Tuilerie gardens

Everything that has a look also has a design, according to the common definition. The word ‘design’ was created to fit the needs of nascent industrial production in the early nineteenth century. The industrial revolution and mass consumerism forced a compromise between artists ateliers and factories. Bauhaus was one of the first and remains the most influential schools of design. It's main idea was to create functional, cheap and aesthetically pleasing objects so that people of lower social echelons could access 'beauty', which was then considered a luxury. However, there is one reservation that aesthetic qualities are determined based on an object’s function, and not the other way around; an armchair is to be sat upon, and any attempt to move it equal a daily dose of sport. This principle distinguishes design from art. In late March, the Parisian 14th Pavillon des Arts et du Design trade show demonstrated how fine of a line this is.

Everything that has a look also has a design, according to the common definition. The word ‘design’ was created to fit the needs of nascent industrial production in the early nineteenth century. The industrial revolution and mass consumerism forced a compromise between artists ateliers and factories. Bauhaus was one of the first and remains the most influential schools of design. It's main idea was to create functional, cheap and aesthetically pleasing objects so that people of lower social echelons could access 'beauty', which was then considered a luxury. However, there is one reservation that aesthetic qualities are determined based on an object’s function, and not the other way around; an armchair is to be sat upon, and any attempt to move it equal a daily dose of sport. This principle distinguishes design from art. In late March, the Parisian 14th Pavillon des Arts et du Design trade show demonstrated how fine of a line this is.

14, 500 euros a pop

The eighty stands showcase the crème de la crème of art and design merchants. You can find anything from antiquated jewellery and paintings to large-scale photoshop masterpieces or a lamp in the shape of cerebral hemispheres. The organisers were expecting to see 45, 000 visitors over the five days of the fair. Next to the African art you can see modern painting and decorative twentieth century art and design stands.

One of the first ones belonged to the London Carpenters Workshop Gallery. An eyecatching dark-grey steel cupboard (Buffe Nouvelle Zélande) stands out from an otherwise light decor. Simple, crude construction. The structure is almost raw – the cupboard appears unfinished. Long, steel sheets hammered together on one side bend to all sides on the other. It's as if the French designer, Vincent Dubourg, wanted to show the different phases of creating a piece of furniture. Above the cupboard there's an equally deconstructivist shelf – is it also a victim of a similar explosion? The small tag contains a big price – 14, 500 euros (£12, 767, plus VAT). Is this still design or has it become art already? 'It is still design, because all of these objects are perfectly functional,' responds Loïc Le Gaillard, who runs the Parisian stand. What if the piece of furniture were only half-functional, like the Nouvelle Zélande? 'Our gallery is looking for a union between furniture and sculpture. I wouldn’t try to demarcate the border between one and the other,' he explains.

A few steps further your attention is drawn by a different explosion – one of colours. Parisian gallery Perimenter offers an armchair made out of colourful rubber. Rubber stripes connected with felt press against one another to form the seat and the backrest. It's hard to tell if it is stable; a Please Do Not Touch accompanies every piece. 'The armchairs are authored by Brazilian designers, who wanted to capture the joy of life which is so characteristic of their motherland,' explains Nicolas Chwat, the gallery's director. Does a particular European design style exist? 'There is no European design, it differs from one country to the next,' he explains, occasionally interrupting his speech with a pleading 'Please, don’t touch' towards the stand’s guests. Again - is this a stand or a museum? Art or design?

A few steps further your attention is drawn by a different explosion – one of colours. Parisian gallery Perimenter offers an armchair made out of colourful rubber. Rubber stripes connected with felt press against one another to form the seat and the backrest. It's hard to tell if it is stable; a Please Do Not Touch accompanies every piece. 'The armchairs are authored by Brazilian designers, who wanted to capture the joy of life which is so characteristic of their motherland,' explains Nicolas Chwat, the gallery's director. Does a particular European design style exist? 'There is no European design, it differs from one country to the next,' he explains, occasionally interrupting his speech with a pleading 'Please, don’t touch' towards the stand’s guests. Again - is this a stand or a museum? Art or design?

'21st century design'

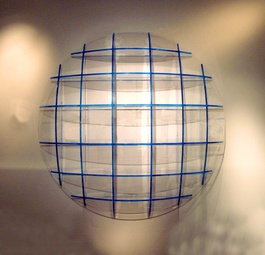

'Do not bother yourself with such questions, it’s a rather simple matter. Design is a way of life,' says Matthieu de Prémont, director of the Spectra gallery which is showcasing an acrylic glass furniture collection. One product which enjoys particular popularity among the stand’s visitors is a hanging shelf in the shape of a hemisphere. There does not seem to be much space when you look at Blue Planet, but it’s an optical illusion; the transparent structure has numerous spacious compartments. Functional and beautiful. There is one ‘but’ – it is produced in quantity and only eight have been made, which drives the price up to exorbitant 14, 000 euros (£12, 327) a piece. From consumer goods to luxury – is this the trajectory of the development of design in the twenty-first century?

'Do not bother yourself with such questions, it’s a rather simple matter. Design is a way of life,' says Matthieu de Prémont, director of the Spectra gallery which is showcasing an acrylic glass furniture collection. One product which enjoys particular popularity among the stand’s visitors is a hanging shelf in the shape of a hemisphere. There does not seem to be much space when you look at Blue Planet, but it’s an optical illusion; the transparent structure has numerous spacious compartments. Functional and beautiful. There is one ‘but’ – it is produced in quantity and only eight have been made, which drives the price up to exorbitant 14, 000 euros (£12, 327) a piece. From consumer goods to luxury – is this the trajectory of the development of design in the twenty-first century?

'Twenty-first century design is a non-existent concept. Maybe with the exception of Ikea – voila modern design - which is functional, cheap and aesthetically pleasing,' says Marc-Antoine Patissier, the director of HP Le Studio which represents Italian designers inspired by Japanese art. 'In real design you want to get rid of the unnecessary, get to the nature of an object. Furniture shown here is 'over-designed', it is almost as if every one of the pieces is screaming Look at me! Yet we couldn't all live in a flat where every object attracted attention. It would be hard to live with.'

Artistic and static design

Even so, there is a fair bit of purchasing going on during the trade fair. The buyers do not seem to be bothered by the tawdry designs or the eye-popping prices. 'I have nothing against objects that do not serve a specific purpose,' says Patricia, who I meet at one of the stands. 'I think that we are surrounded by artistic design at the trade show, and I like that mix.' Where does the interest for 'artistic design' come from?

'We used to decorate our homes with sculptures. Today nobody buys them; they are products designated for institutions, museums or companies. Today, people want to have original furniture instead of sculptures,' explains Andrew Duncansoz of Modernity, a gallery representing Scandinavian designers. In the small stand you will find all of the big names: Gio Ponti, Gerrit Rietveld, Verner Panton… clear forms, simple connections of materials, armchairs that serve to be seated upon… all of this from the 1930s, 1950s and 1960s. Rubber armchairs and post-detonation cupboards are proof that whilst today’s designers have had their shot, they have failed to surpass their masters.

'We used to decorate our homes with sculptures. Today nobody buys them; they are products designated for institutions, museums or companies. Today, people want to have original furniture instead of sculptures,' explains Andrew Duncansoz of Modernity, a gallery representing Scandinavian designers. In the small stand you will find all of the big names: Gio Ponti, Gerrit Rietveld, Verner Panton… clear forms, simple connections of materials, armchairs that serve to be seated upon… all of this from the 1930s, 1950s and 1960s. Rubber armchairs and post-detonation cupboards are proof that whilst today’s designers have had their shot, they have failed to surpass their masters.

Images: © PAD

Translated from Nie ma przyszłości dla designu?