What future for welfare?

Published on

Translation by:

veronica newington

veronica newington

The differing welfare systems in Europe suggest that there is no one social model but rather a common social conscience. However, certain models are functioning better than others.

Although certain essay writers in the early 80s spread the idea of a welfare state “in crisis”, positing its possible demise, studies carried out since the end of World War Two have demonstrated the existence, in Europe, of a genuine common heritage with respect to social protection. A model built on nearly one hundred year-old pillars of social conscience, labour relations, public services; all concerning solidarity and social security systems.

”Three worlds of welfare capitalism”

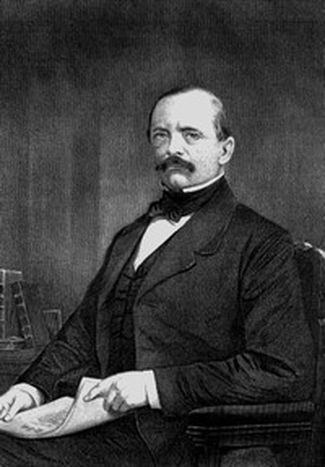

Two events - German Chancellor Bismarck’s social laws at the end of the 20th century and the publication in 1942 of a report by an English economist, Beveridge - were key to the creation of this common European capital. It went on to form the basis of the “balance between economic prosperity and social justice” demanded by the 15 EU member states at the European Council at Barcelona in 2002. This was the result of a clever blend of binding legal clauses and collective negotiation.

In 1990, the economist Gøsta Esping-Anderson systematised the diverse range of welfare provision, laying out “three worlds of welfare capitalism” which correspond with various national versions of the European social model. The first, conservative, model exists mostly in continental Europe. Drawing its inspiration directly from Bismarck’s system, it relies on the principle of employee contributions and tends to guarantee workers’ salaries. The second, Anglo Saxon and liberal model, is the brainchild of Beveridge. Its aim is to combat poverty and unemployment with a principle of selectivity. The Social Democratic model, applied mostly in Northern Europe, takes up the principle of universality (which Beveridge also advocated), in its concern to redistribute state revenue fairly. Consequently, only citizens and residents have access to basic benefits. As well as differing in their objectives and social security access criteria, these three paradigms work in different ways.

Now facing the need for deep-seated changes, particularly in relation to globalisation and new public aspirations, these three models have become the object of fierce controversy. This debate fuelled the electoral race in Germany and France.

An unavoidable crisis?

It is often the systems inspired by Bismarckian ideals that now seem in the worst shape. Conceived according to realities which have changed through the decades, they increasingly struggle to respond to contemporary expectations. Europeans’ needs have changed as new social risks have emerged. In the move towards a post-industrial society, certain skills have quickly become obsolete, job security has disappeared with little compensatory social protection, professionals have more than one career, value-added services are outsourced and industry relocated to cheaper places, often abroad. Our behaviour has also changed with ageing populations, single-parent families, working women, the difficulty of reconciling working and family life and the demand for security for all. Lifestyles too have evolved due to urbanisation, greater mobility, less reliance on local support networks and greater dependence of vulnerable people on public services.

At the same time, European governments whose social security systems follow the Social Democratic or Liberal models are embarking on reforms which seek to increase the individual’s responsibility, largely inspired by the idea of “making work pay”. The influence of this idea has transcended borders and these theories have helped to put pressure on the model sketched out by Brussels in a Europe of 15 member states. A true picture of the critical state of the European social model is, however, not complete without consideration of the ideological tensions, the challenges posed by the last enlargement (economic liberalism, the EU budget, consolidation of EU institutions and social dumping) and European integration’s loss of momentum given growing doubts over subsidiarity and the decision-making ability of a Europe of 25 or even 27.

Sluggish growth and selfish member states

The solidarity inherent in the concept of the welfare state is also in a bad way. When sluggish growth encourages the desire to eliminate anything likely to impede the economy, the idea according to which social security can only (and should only) follow on from a healthy economy gains credence. Still more worrying is the question of the institutional capacity, indeed the will, of the new Central and Western European nations to adopt the European social model. Moreover, although many nations are still attached to the EU’s social dimension, the 25 member states are increasingly sensitive to the national advantages they can gain from their European commitments. The drive for an inter-governmental approach for these matters exacerbates this tendency and the European Commission is not trying to counterbalance this attitude change. In the absence of a stimulating agenda it does not seem to be in a position to take the helm when it comes to European social dialogue.

In these unfavourable circumstances, Tony Blair’s proposal to think of ways to modernise the European social model and better adapt it to new realities and social challenges is pressing and should be taken on board.

Translated from Grandeur et décadence du modèle social européen