What does the High Court's ruling mean for Brexit?

Published on

England's High Court has ruled that the British Government must consult Parliament before it can trigger Article 50 and start the process of leaving the EU. Is this an opportunity for a more inclusive debate on one of the most contentious issues in modern British political history? Or just another sign that, despite Theresa May's confidence, Brexit is going to be anything but simple?

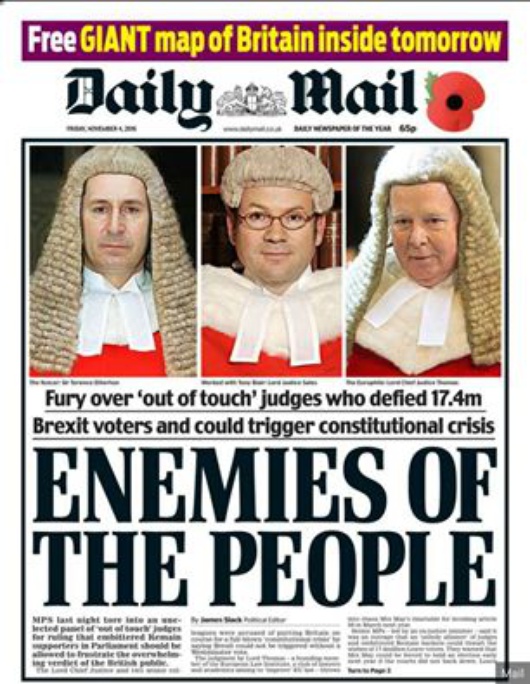

After three weeks of deliberation, the High Court of Justice has handed down what is widely being described as one of its most significant rulings in decades. The government, it says, does not have the right to trigger Article 50 of the Lisbon Treaty, which would formally start the process of leaving the European Union, without consulting members of Parliament.

The government has promised to appeal the ruling at the Supreme Court, but this hasn't stopped leading 'Leave' campaigners from weighing in - acting UKIP leader Nigel Farage warned of a "betrayal" of the British people, who voted by 52% to 48% to leave the EU in June's referendum.

Political commentators have been at pains to point out that, despite the ruling, the chances of MPs voting to block Brexit altogether are almost zero. Even Gina Miller, the investment manager who brought the case against the government, stressed in her statement outside the courthouse that the ruling is "not about how anyone voted," saying instead that "this case was about process, not politics."

So, unless the government's appeal is successful, how might this 'process' now be altered?

The most immediate question will be how it affects the Brexit time frame. Theresa May had said she wanted to begin talks with the EU by the end of March 2017. Given the general consensus that negotiations will take two years, that plan would see the country officially leave the bloc some time in early 2019. But if the terms of a future deal with the EU are going to have to be agreed by parliamentarians - many of whom voted to remain in the first place - that timetable may well go out of the window.

This brings us to the second question: how will it ever be possible to come up with a deal that Parliament would accept? The two opposing campaigns in the Brexit referendum, and the narrow margin by which the 'Leave' camp won, highlighted the division of opinion on the UK's place on the European stage. Obtaining Parliament's approval on a path forwards now is likely to be much easier said than done, especially as this means approval from both the House of Commons and the House of Lords.

This brings us to the second question: how will it ever be possible to come up with a deal that Parliament would accept? The two opposing campaigns in the Brexit referendum, and the narrow margin by which the 'Leave' camp won, highlighted the division of opinion on the UK's place on the European stage. Obtaining Parliament's approval on a path forwards now is likely to be much easier said than done, especially as this means approval from both the House of Commons and the House of Lords.

None of this is going to reduce the frustration felt in Brussels at what is perceived as the 'mixed messages' the UK has already been sending out about its intentions.

Until now, Theresa May has been largely keeping her cards to her chest when it comes to the details of her Brexit plans – the British public know they are leaving the EU, but not where they're going. Now, with a chamber full of MPs likely to be legally entitled to vote on the issue, it’s hard to imagine that her "Brexit means Brexit" mantra will cut it for very much longer.