What does terrorism mean in Europe anyway

Published on

Translation by:

Cafebabel ENG (NS)On 18 October EU counter-terrorism coordinator Gilles de Kerchove warned about governments crying wolf during recent threats of a new terrorist alert. The last time the EU continent was attacked was during the London bombings of 2005. The term ‘terrorism’ has taken on various meanings

The Eiffel Tower suffers a false bomb alert in mid-September. In early October, Francewarns its citizens in Britain to be vigilant on public transport amidst fears of an imminent terrorist alert. The French government would have it that the threats from Al-Qaeda come from the islamic Maghreb. Why is Europe so threatened by terrorism? Is British writer Percy Kemp right when he tells the French daily Libération that ‘our governments prefer to see us live in a permanent state of terror’? What is terrorism anyway?

‘Terrorism’ Europe

The word is frightening, it’s not really understood. Definitions in general place the term as meaning a collection of violent acts committed by an organisation. French dictionaries attribute various different goals from it. Larousse stipulates that it’s ‘blackmail on a government’, the ‘satisfaction of hatred’. The Petit Robert says it ‘disturbs a country’ – the EU definition is that it ‘may seriously damage a country or an international organisation’. The Universalis adds that its ‘trying to make a psychological impact’ and the creation of a ‘climate of insecurity’. The Royal Spanish Academy calls it ‘spreading fear’.

There’s also a difference between guerillas and minority movements without a guerilla. The word guerilla means ‘little war’ by clandestine groups. The Al Qaida network aside, the most mediatised and listed ‘terrorist organisations’ on EU lists are: Farc (Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia, since 2002) in South America, the PKK (Kurdish Kurdish Workers Party, since 2004) and the LTTE (Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam) in Asia and the PFLP (Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine since 2002) in the Middle East. In Europe it’s the IRA (Irish Republican Army) splinter groups Real IRA and Continuity IRA, ETA (Euskadi Ta Askatasuna or 'Basque Homeland and Freedom', since 2000 in the UK) and various Corsican movements.

Is terrorism islamism?

From independences to the liberations of oppressed peoples, the diversity of various causes only nuance the amalgam between terrorism and islamism as created by the French and European authorities. You can see the amalgam in the methods of repression that have been put in place, especially since 11 September 2001, when a series of attacks on America by the Taliban changed the world forever.

Prior to the events of 2001, only six countries in the European Union had specific anti-terrorism legislation – Germany, Spain, France, Great Britain, Italy and Portugal. 9/11 meant that these national legislations were harmonised, especially with a common basis on punishments and sanctions. This includes an eight years prison sentence for participating in a terrorist attempt and fifteen years for leading a terrorist group. 9/11 also defined a common definition of terrorism: a ‘structured association of more than two people and acting in a concerted manner to commit terrorist infractions,’ without ever precising what a ‘terrorist infraction’ actually amounts to.

Countries have adapted to the international dimension of islamist terrorism by creating new incriminations. This includes more extensive control on the movement of foreigners from ‘sensitive’ countries and specific ‘islamist industry’ surveillance, say on mosques and linked charitable activities. The states have responded to criticism of their security policy, legitimising their decisions by revindicating the defenders of ‘individual freedom’. They’ve favoured a ‘preventative’ policy rather than a repressive or secure one.

Terrorism by Dostoyevsky and Sartre

Instead of getting banged up in this collective psychosis, why not try to discern the motivations which lead violence to an ideal? Dostoyevsky once wrote: ‘I begin by proposing unlimited freedom, but end in absolute despotism’. Doesn’t fulfilling an ideal implicate some form of violence anyway? Act five of Jean-Paul Sartre’s Dirty Hands ('Les Mains Sales', 1948) illustrates the tension between governor and imposer, like between terrorism and resistance: ‘I have dirty hands. Right up to the elbows. I’ve plunged them into filth and blood. But what do you hope? Do you think you can govern innocently?’

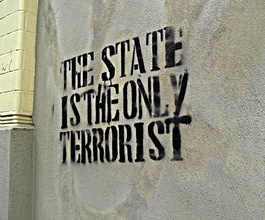

French resistance member Raymond Aubrac pointed out that he was just as much a ‘terrorist’ for going against the system during the Vichy government era. Jean Pierre Valabrega, the psychoanalyst author of Terrorism and Counter-Terrorism (2003), goes on to define the main cause of terrorism as being the resistance to state terrorism. ‘Initial terror comes from the states and those who have to exercise power. All of the ideologies, beliefs and conflicting religions help manifest a state of terror.’ It’s relative, he says: if you consider the state as the principal organ of terrorism, then maybe all of the ‘resistors’ who are born out of it and take shape because of it aren’t the real terrorists, but the anti-terrorists. ‘To try and reestablish some truths,’ continues Sartre, ‘resisting infection is not an infection. Resisting oppression is not an oppression.’ Who are the terrorists? Who are the counter-terrorists? Contemporary islamist movements call some people to jihad and universal islam. They equally exhort a rejection of American consumption and imperialism, like the left-wing terrorist movements of sixties to eighties Europe did. Do the means justify the ends?

French resistance member Raymond Aubrac pointed out that he was just as much a ‘terrorist’ for going against the system during the Vichy government era. Jean Pierre Valabrega, the psychoanalyst author of Terrorism and Counter-Terrorism (2003), goes on to define the main cause of terrorism as being the resistance to state terrorism. ‘Initial terror comes from the states and those who have to exercise power. All of the ideologies, beliefs and conflicting religions help manifest a state of terror.’ It’s relative, he says: if you consider the state as the principal organ of terrorism, then maybe all of the ‘resistors’ who are born out of it and take shape because of it aren’t the real terrorists, but the anti-terrorists. ‘To try and reestablish some truths,’ continues Sartre, ‘resisting infection is not an infection. Resisting oppression is not an oppression.’ Who are the terrorists? Who are the counter-terrorists? Contemporary islamist movements call some people to jihad and universal islam. They equally exhort a rejection of American consumption and imperialism, like the left-wing terrorist movements of sixties to eighties Europe did. Do the means justify the ends?

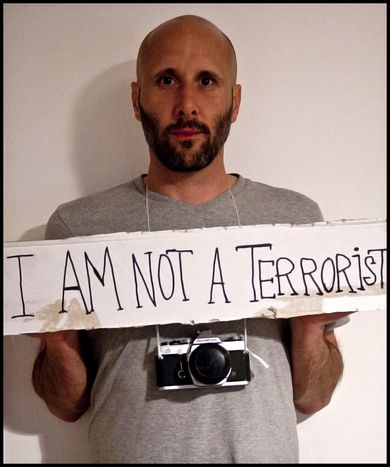

Images: main (cc) monaxle; in-text (cc)ruSSeLL hiGGs/ both courtesy of Flickr

Translated from Terrorisme : menace réelle ou concept fourre-tout ?