‘W’ by Oliver Stone: what about Europe's improbable leaders?

Published on

Translation by:

Helen SwainAn unashamed America goes on the big screen to ruminate on its history. But in Europe, directors are too dependent on public subventions to dare make biopics about public figures during their lifetimes

‘It's going to be very difficult -- (applause) -- but I think it's going to be very difficult to find somebody, another man who is really -- (applause) -- and courageous like George Bush. (Applause).’ Thus ended Silvio Berlusconi’s toast to Bush during his visit to the White House on 12 October. ‘There has never been a moment when I saw in him interests which are not general interest. I never saw biased interest. There has never been a moment when I saw in him something different from a very sincere and pure feelings and sentiment,’ continued the Italian prime minister. ‘Our friendship is a special friendship which has its roots in common values, in sharing a world which is inspired by love for democracy and freedom.’ Perhaps Berlusconi was not so far from Oliver Stone's viewpoint.

Big screen caricature

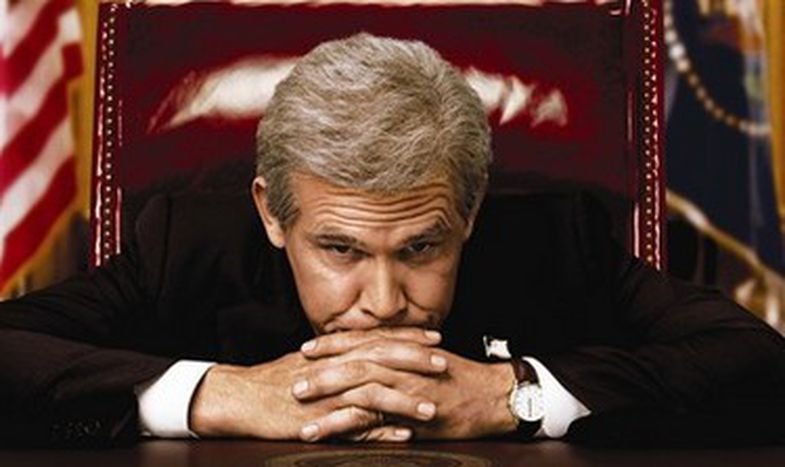

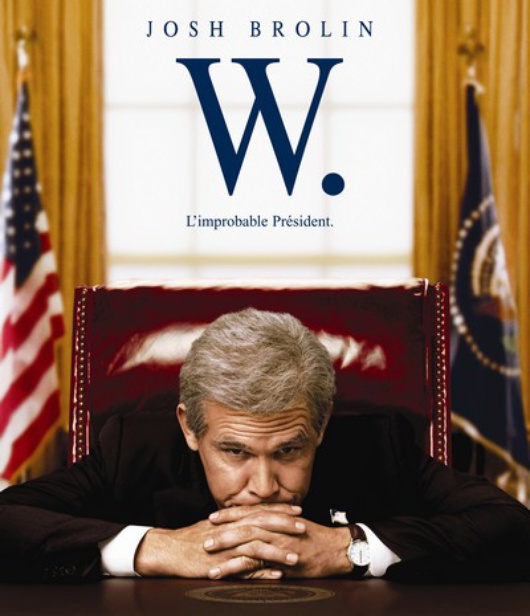

The American director’s W (with Josh Brolin in the main role) was released just before the elections, and is a partial and slightly grotesque portrait of a picturesque figure. Stone has chosen to present certain rather striking aspects of the 62-year-old president, such as his Oedipal relationship with his father, his almost fairytale love story with his wife Laura (played by Ellen Burstyn), his alcoholism, his religious beliefs and, above all, the war in Iraq.

The American director’s W (with Josh Brolin in the main role) was released just before the elections, and is a partial and slightly grotesque portrait of a picturesque figure. Stone has chosen to present certain rather striking aspects of the 62-year-old president, such as his Oedipal relationship with his father, his almost fairytale love story with his wife Laura (played by Ellen Burstyn), his alcoholism, his religious beliefs and, above all, the war in Iraq.

However, there are at least two fundamental matters which the director does not approach: September 11 and Bush's election (although, of course, this has already been dealt with by Michael Moore in Fahrenheit 9/11). Stone's Bush is a sort of numbskull who, partly by chance and partly by luck, finds himself president of a country; who eats nothing but sandwiches and hamburgers; and to whom, finally, we almost find ourselves warming. Is this Stone's message? The only problem with which he seems to be really concerned is the war in Iraq. Former US secretary of state Colin Powell (played by Jeffrey Wright) finds himself obliged to make a rather implausible anti-militarist speech to the public, while the images of soldiers' wounded bodies take care of the rest.

It is clear that Stone's objective is not to write history – neither he nor the screenwriter, Stanley Weiser, used any firsthand sources. None of the ‘real’ figures were contacted and it would seem that much of the screenplay is based on two books: State of Denial: Bush at War, Part III (2006) by Bob Woodward and The Faith of George W. Bush by Stephen Mansfield (2004).

Next up: a film about Sarkozy?

While, for American cinema, making films from the biographies of men who ‘made history’ (as Stone already did in 1995 with Nixon and in 1991 with JFK) is relatively commonplace, on the other side of the Atlantic, we are more used to denunciative or historical cinema. Take the first film on Italian dictator Mussolini, which is mainly about his death (Mussolini: Ultimo atto/ 'Final Act', Carlo Lizzani, 1974) or the recent film about Hitler (Olivier Hirschbiegel’s Der Untergang/ 'Downfall', in 2004).

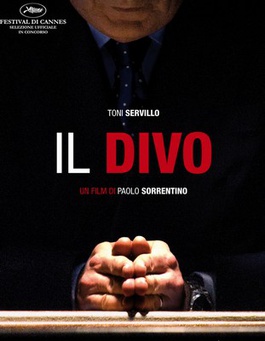

However, cinematic portraits of current politicians are still quite rare. In Italy, Nanni Moretti attempted it in 2006 with Il Caimano. While the director insisted that the film was not about Berlusconi, a number of (right-wing) politicians asked for the release date to be put back so as not to coincide with the April elections, in which the prime minister was re-elected. More recently, Paolo Sorrentino directed a film about  Andreotti (Il Divo, 2008). In France, an attempt was made with Francois Mitterand; Le Bon Plaisir (Francis Girot, 1984) both revealed and hushed up the existence of the socialist president's love child. In 2005, Robert Guédiguian tried to portray Mitterand's private life at the end of his political career (Le Promeneur du Champ de Mars/ The Last Mitterrand, 2005). Germany is getting ready for a film about former chancellor Helmut Kohl, which will be released in 2009 – but apparently only for television.

Andreotti (Il Divo, 2008). In France, an attempt was made with Francois Mitterand; Le Bon Plaisir (Francis Girot, 1984) both revealed and hushed up the existence of the socialist president's love child. In 2005, Robert Guédiguian tried to portray Mitterand's private life at the end of his political career (Le Promeneur du Champ de Mars/ The Last Mitterrand, 2005). Germany is getting ready for a film about former chancellor Helmut Kohl, which will be released in 2009 – but apparently only for television.

Europe undeniably respects history: the EU is just over fifty years old and is today trying to bring together peoples who merely co-habited during the period between the world wars. European film seems to reflect this approach. Erwan Benezet, a journalist for the newspaper Le Parisien who co-wrote the book Washington Hollywood: Comment l'Amérique fait son cinéma/ How America makes films (Armand Colin, 2007) with Barthélémy Courmont, affirms that: ‘Historically, the United States is the only democratic country to have fully utilised cinema as propaganda (supervisory control is insisted upon in Hollywood, for example). The three other nations to have used cinema in this manner – Germany, the URSS and Italy during certain periods – had authoritarian governments or dictators at the time. American cinema is also remarkable for its incredible reactivity with regard to national and international history.’

Witch hunts and US film

During the sixties, America produced films about the Vietnam War (1960-1975) before the war ended. There have been films about Iraq although soldiers are still in situ (two examples are Lions for Lambs by Robert Redford and In the Valley of Elah by Paul Haggins, both released in 2007). In the US nobody found this scandalous, as it would have been in Europe. In his current releaseMiracle at St. Anna, Spike Lee tells the story of the Buffalo Soldiers against the backdrop of the Italian civil war; when the film's release caused national outrage, the director's only response was to shrug politely.

However, according to Erwan Benezet again, ‘It is also a question of money. Things change when budgets can be independent of the state which controls history. In France or Italy, films are too often dependent on funding to be sufficiently independent. This is not the case in the United States, where film-making is an industry in its own right, with greater liberty of movement and opinion. The last time the government tried to control film-making was during the 1950s witch hunts.’

Translated from George W. Bush di Oliver Stone: un Presidente improbabile