Vesna Goldsworthy: 'Radovan Karadzic is related to me'

Published on

Translation by:

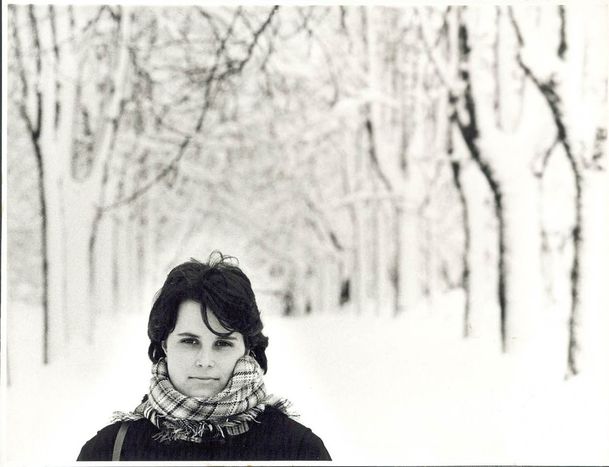

Nabeelah ShabbirThe Belgrade-born journalist and author of ‘Chernobyl’s Strawberries’, 47, on fighting cancer, the traumas of war, her eccentric grandmother and her war criminal cousin

Vesna Goldsworthy is visiting Poland for a literary evening as a guest of the British Council. She is an elegant and distinguished lady, comfortable in her forty something skin. She has that distancing which is typical of Balkan women mixed with an English reserve and an ironic sense of humour, no doubt built up after having spent many years of her life in the British Isles.

Vesna Goldsworthy is visiting Poland for a literary evening as a guest of the British Council. She is an elegant and distinguished lady, comfortable in her forty something skin. She has that distancing which is typical of Balkan women mixed with an English reserve and an ironic sense of humour, no doubt built up after having spent many years of her life in the British Isles.

Born in 1961 in Belgrade, in then Yugoslavia, Vesna Bjelogrlic studied in France, but spent the majority of her adult life in London, where she moved after meeting her English husband. She is a professor at Kingston University in Surrey, although she also spent time at the BBC world service for Serbia. Above all, she is a writer.

Her book Chernobyl’s Strawberries was written in 2003, after Goldsworthy discovered that she had cancer and doctors gave her six months left to live. She understood then that if she died, her two year old child, being raised in the UK, would not only lose his mother but his only window to his Balkan roots. She decided to write her memoirs. What began as a book from a mother to a son became a bestseller.

Love in the time of uranium

The title Chernobyl’s Strawberries was inspired by the strawberries that Goldsworthy once offered an Englishman in 1986. ‘I started to record my memories, beginning in spring 1986. For the whole world it was the year of the atomic bomb explosion in Chernobyl. For me, it was the year that my future spouse first came to Belgrade, where I managed to convince him that Serbian strawberries tasted a hundred times betters than English strawberries.’ The strawberries, symbol of a growing love between the two, could paradoxically have contributed to Goldsworthy's contracted breast cancer; perhaps they had been radioactively contaminated after the Chernobyl fallout.

Listen to Vesna reading an excerpt of 'Chernobyl's Strawberries'

There could be many other reasons for Goldsworthy’s illness – the trauma of war, for example. ‘I was with my other half in England during the eighties and I got a visa without many problems. Later, when I worked at the BBC presenting reports about the Yugoslav war, I realised that Yugoslavia’s break-up had been very easy for me. The ease of my journey caused me many problems for many years after, when I saw my compatriots escaping the war. I realised then that my luck also brought with it a responsibility that I had to assume an interest in politics and tell the world what happened.’

The war awoke in the journalist worries which had up until then been unknown to her, related to identity and the pertinency of a nation. ‘When NATO bombed Serbia, I prayed at the same time for the pilots and also the people on the ground. It was the worst moment of my life, the most schizophrenic, where I was observing the war but not being capable of saying whose side I was on. War converted the subject of identity into something painful. I often think that the stress related precisely with that provoked my illness.’

Broken identity

When Yugoslavia broke into pieces, for a long time Vesna found it hard to accept the truth. ‘I lied to myself. I thought that this war would finish itself in some secret fashion. That it would disappear. It turned out that Radovan Karadzic, a symbol of war crimes in Yugoslavia, was related to me on one side of my family in Montenegro. It’s the banality of war, in which the members of each and any family are potential assassins. When one million Serbs were abandoning Carniola in August 1995, I was sitting at a BBC news desk. A river of refugees were fleeing, and I locked myself in the bathroom, not able to stop myself from crying. It was difficult to accept that the Serbs suffered and that those same Serbs had generated that suffering,’ she says, in a voice which still trembles.

When Yugoslavia broke into pieces, for a long time Vesna found it hard to accept the truth. ‘I lied to myself. I thought that this war would finish itself in some secret fashion. That it would disappear. It turned out that Radovan Karadzic, a symbol of war crimes in Yugoslavia, was related to me on one side of my family in Montenegro. It’s the banality of war, in which the members of each and any family are potential assassins. When one million Serbs were abandoning Carniola in August 1995, I was sitting at a BBC news desk. A river of refugees were fleeing, and I locked myself in the bathroom, not able to stop myself from crying. It was difficult to accept that the Serbs suffered and that those same Serbs had generated that suffering,’ she says, in a voice which still trembles.

The theme of identity manifested itself in Goldsworthy’s work. She realises that even in language she experiments with her schizophrenia. ‘My thoughts depend on what I think about in that moment. English has become my language, but there are many things, names, feelings, which exist in my head as Serb words. To be bilingual is weird, for example I only learnt to cook in England and the main part of my related vocabulary is therefore only in English. In the same way, I am not able to describe many themes related to Serbia in English, because in English very often those words simply don’t exist which can best fit with the Serb meaning. If I think of my childhood and youth, I think in Serbian, and on the contrary if I think of what I am going to get for lunch, it’ll be in English.’

New ‘me’ in a new language

‘Writing in another language completely frees up other forms of creativity. This is part of the history of Europe. You can’t say that Vladimir Nabokov was not a good writer because he was Russian and wrote in English. In the best of cases, the writer is a new ‘me’ in a new language, For this reason I wouldn’t let Chernobyl’s Strawberries be translated into Serb. I knew that if I got involved with this I would end up writing another book.’

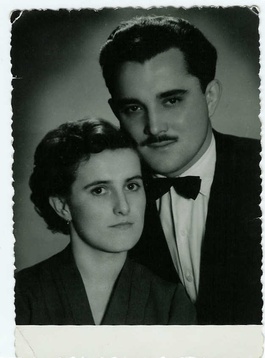

Goldsworthy comes from a family of high standing in the Balkans. When she discusses the more bizarre characters in her book – such as her eccentric grandma – a mysterious smile breaks out upon her face and her eyes begin to water. ‘My Montenegran grandma always said what she thought. She wasn’t contaminated by political correction. Her point of view was always very simple and funny too: for a grandmother, the world divides itself into ‘us’ and ‘them’. Us – the Serbs and other Christians – and them; the Turks who took over the rest of the world, in Africa and Asia. She was also very jolly. When I visited her with my husband in Montenegro, she described to him in detail the technique of cutting and marinating human heads. Of course she had never seen decapitated heads in her life, but she thought that it was necessary to tease an Englishman.’

The rounds of history in the Balkans oblige women who live there to be especially strong. ‘Men died in later wars, disappeared, and the women were left alone and had to defend themselves in some way. When I lost my hair after chemotherapy, I had to hide my bald head, and one day I looked in the mirror and saw in my face the faces of all these women. I thought that in this moment, I was in my place in the queue. That gave me strength.’

Article first published on 16 February 2008

Translated from Vesna Goldsworthy: Miłość w czasach Czarnobylu