Verdict: guilty

Published on

Translation by:

megan rogers

megan rogers

“Rogue States” for Americans, “STIPS” for Europeans: two names for countries failing to abide by International Law. And two methods to try and make them take the right path again.

"One of the great challenges of our age is to deal with rogue states, because their sole objective is to destroy the international system", declared American president Bill Clinton during the first year of his mandate. However, the punitive strategy adopted by the United States with regard to these "rogue states" seems far from successful.

"One of the great challenges of our age is to deal with rogue states, because their sole objective is to destroy the international system", declared American president Bill Clinton during the first year of his mandate. However, the punitive strategy adopted by the United States with regard to these "rogue states" seems far from successful.

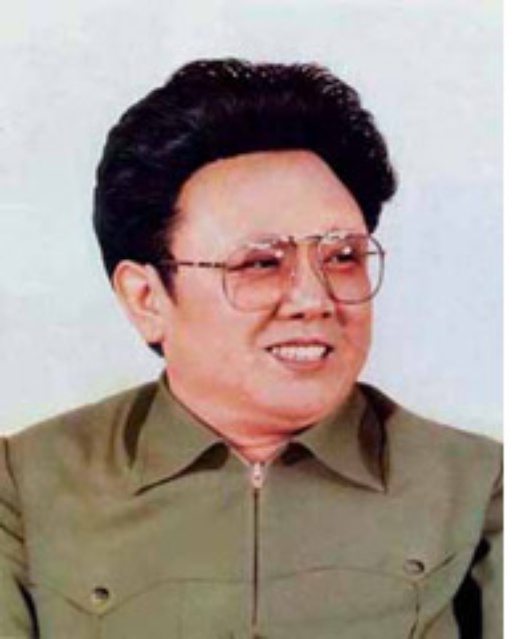

Initially restricted to seven countries - Iraq, North Korea, Cuba, Iran, Syria, Libya and Sudan - the expression rogue state designates “recalcitrant and outlaw states that not only choose to remain outside the family of democracies but also assault its basic values”. In short, nations which, according to Washington, support international terrorism, develop non-conventional armament programs (such as manufacturing biological, chemical or nuclear weapons), encourage the drug trade or oppress their own populations. These rebellious entities also present the characteristic of being anti-Western, and thus likely to threaten American "vital interests". The theory of the rogue state, enshrouded in a blurred legality and brought to the forefront by the attacks of September 11, turned into that of the "axis of the evil", then into that of "outposts of tyranny", giving rise to the disputed doctrine of "preventive war".

American containment policy

Generally, the United States chooses to pressure the rogue state concerned; either to destabilise its regime and support its fall, or to encourage it to change its behaviour. The variety of means relied on is wide: military threats; support of internal insurrections; embargos; severe economic sanctions and financial asphyxiation; or termination of diplomatic relations. For example, under the Iran-Libya Sanctions Acts of 1996, "secondary" sanctions were employed, which penalised foreign companies investing in the oil industries of both countries, whilst the Helms-Burton law envisages an identical punishment for companies investing in the American assets expropriated by Cuba at the time of the Castrist revolution in 1959.

Nevertheless, military action remains the central element of American foreign policy with respect to delinquent countries. Whilst there are legal and legitimate procedures (based on chapter VII of the United Nations Charter and involving the Security Council) to confront the many threats weighing on global peace, the United States frequently acts outside the UN framework. Or, as Madeleine Albright, Secretary of State under Clinton, put it: "The United States will act multilaterally when possible, but unilaterally when necessary”. It is under the pretence of an intervention aimed at countering a dictatorial government suspected of holding weapons of massive destruction that the United States arrived in 2003 in Iraq. For Washington, the recalcitrant countries must be isolated and excluded from the international community because to ostracise a country is to attack its legitimacy and credibility on the global scene, which also creates after-effects of a psychological, diplomatic and economic nature.

The European "critical dialogue"

It is interesting to note that the European Union calls these countries not rogue states but STIPS (States Threatening Peace and International Safety), a more technical term which favours non-coercive action. Indeed, the EU hopes to bring changes in the attitude of the STIPS by reactivating diplomatic or economic relations. Syria, for example, is engaged in the Barcelona process, initiated in 1995 by the EU with the objective of creating a Mediterranean free trade area before 2010. This "critical dialogue" considers that the rogue states issue is only the direct result of Washington’s foreign policy. Moreover, Europeans have their reservations about accepting the purely subjective American definition of rogue state, insofar as it could hinder their own economic and political interests. To align themselves with the American perception of particular Middle Eastern countries (like Libya, which is regaining the European leaders’ favours) would thus amount to depriving themselves of many economic opportunities.

Harmful intransigence

Whilst a repressive or even punitive policy undeniably contributes to containing the dangerous country, it also has perverse effects such as the consolidation of the regimes concerned; renewal of popularity of the leaders in place; the growth of nationalism, religious fanaticism and the rejection of the international community; hindering economic development of the regions concerned and risks of ethnic or religious disintegration. Unilateral sanctions, or sanctions imposed with the guilty complicity of the UN, therefore seem to be adopted to the detriment of humanitarian goals and international stability. As a result, today many experts plead for a policy of positive incentives with regard to theses "rogues".

Translated from Verdict : coupables