Using drones to punish speeding

Published on

Translation by:

Monica BibersonFrom 6 November drivers can be watched by drones. After the third-generation radars and video surveillance for obstructive parking, the French state resorts to drastic measures to ensure the safety and comfort of road users. Should we be shocked or pleased?

Jean-Michel smiles away as he drives his 2.3 litre diesel Fiat 550. "It's a good deal," he tells himself. "The mileage is only 34,000 km. And the guy looked like he took good care of it. He was a nice guy. You can tell the engine is still working well." Jean-Michel decides to put it to the test: he lightly steps on the accelerator and goes up to 136 km/h. "Ah, it accelerates well," he notices with satisfaction. But he doesn't have time to enjoy the moment. A flying device quickly overtakes him and starts hovering in front of him: "Gendarmerie Nationale. Please stop at the next toll gate."

Utopian? From 6 November 2015 until 15 January 2016, special drones are being used by the Oise gendarmerie. Their mission is to record drivers who take risks (dangerous overtaking, not keeping a safe distance, etc.) so an operator can then send police officers on motorbikes to intervene. One of their major advantages is discretion: a drone can fly tens of metres away from cars and therefore watch unnoticed. This affords new possibilities in areas "such as in open country where gendarmes can easily be spotted," explains Colonel Marc Boget to the Courrier Picard.

While drones cannot yet detect speeding, drivers like Jean-Michel should be concerned. In France, 260 unmarked police vehicles are already equipped with undetectable third-generation radars. Now every driver can be afraid that the blue Peugeot 308 behind or the yellow Dacia on the left may be equipped with a mobile radar. Video surveillance too is in full expansion: in Marseille, 27,000 penalties were given for obstructive parking in one year. The opinions shared on the web show the unease with which these measures have been greeted: are we protected or threatened by this omnipresent surveillance?

While drones cannot yet detect speeding, drivers like Jean-Michel should be concerned. In France, 260 unmarked police vehicles are already equipped with undetectable third-generation radars. Now every driver can be afraid that the blue Peugeot 308 behind or the yellow Dacia on the left may be equipped with a mobile radar. Video surveillance too is in full expansion: in Marseille, 27,000 penalties were given for obstructive parking in one year. The opinions shared on the web show the unease with which these measures have been greeted: are we protected or threatened by this omnipresent surveillance?

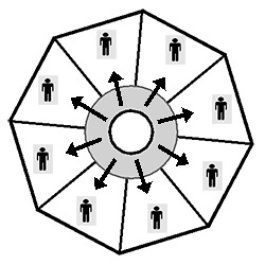

After all, the idea behind these new measures is clear: if you know you are being watched at all times (video surveillance), or if you think you can be checked without your knowledge (third-generation radars, drones), you will refrain from committing any offence. Traditional policing methods are being consigned to the Stone Age: visibility versus invisibility; localisation versus ubiquity; time-specific versus timeless; human error versus implacable punishment. But none of this is new: as early as 1780, the philosopher Jeremy Bentham imagined a new kind of prison: the panopticon. In it, an invisible guard would be placed at the centre of a circle made up of cells. Not knowing when they were being watched, prisoners would be forced to behave themselves.

A prison, really? "We give up a bit of our freedom in exchange for much greater safety," explains Stan in an Arte documentary on surveillance. Stan lives in New Orleans and, significantly, is a member of the NOLA project, which is a new type of community project: everyone contributes to surveillance by installing cameras outside their front doors or in their gardens. The pictures obtained are examined in real time by an operator who can alert the police if there is a problem. Does it work? "In a country which is under surveillance, anything that is watched is by definition suspicious. Even if you do nothing, it doesn't matter," estimates David Lyon of Queen's University. There is an obvious disproportion: we have to film everyone in order to catch a few offenders.

A prison, really? "We give up a bit of our freedom in exchange for much greater safety," explains Stan in an Arte documentary on surveillance. Stan lives in New Orleans and, significantly, is a member of the NOLA project, which is a new type of community project: everyone contributes to surveillance by installing cameras outside their front doors or in their gardens. The pictures obtained are examined in real time by an operator who can alert the police if there is a problem. Does it work? "In a country which is under surveillance, anything that is watched is by definition suspicious. Even if you do nothing, it doesn't matter," estimates David Lyon of Queen's University. There is an obvious disproportion: we have to film everyone in order to catch a few offenders.

Stan and the other supporters of video surveillance give their most potent argument: safety has improved. The decrease in the number of penalties given proves their point. Encouraged by civil society, the state seems to systematically seek to supress the slightest instance of law-breaking. You too may have stolen a few sweets when you were kids, or climbed over a fence to play football. Or, like Jean-Michel, you went over the speed limit for a brief moment. Will transgression, which is part of everyone's identity, disappear altogether? Society no longer seems to trust its members. As Marc Rotenberg, international law expert, concludes: "Our modern societies are faced with a choice. It is a political choice [...]. We can choose not to worry about whether our children will grow up in a world under constant surveillance. We can tell ourselves 'that's modern life, we get used to it'. But I believe that such a future would be a digital prison. We will feel what people feel when they are locked up."

Translated from Des drones pour punir les excès de vitesse