Us and Them: the cold shoulder of Danish hygge

Published on

By Faith Oloruntoba and Michal Skypala

The Western world has been invaded by Vikings once again. This time their conquest has a much simpler goal: to teach us how to be cozy. The Danish word hygge became the worldwide phenomenon of 2016. But there is a less snuggly side to it. Back in its native Scandinavia, not everyone is made to feel hygge.

Hygge. The flicker of candle lights upon an old wooden table with mulled wine; meatballs eaten with family and close friends, gathered around open fire in gentle conversation or contented quietness, sharing a feeling of coziness. Countless publishers have rushed to publish manuals for well-being from the happiest country on Earth. Sadly, not everyone in Denmark is enjoying the benefits of one of its biggest marketing campaigns.

Susan Ahmed is an up-and-coming singer based in Copenhagen. She is having a hard time breaking through the music scene there, mainly due to her non-Danish background. "There are two kinds of hygge here," explains Susan, who was born in Denmark to Iraqi immigrants. "One for immigrants like myself, and the other for Danes."

This negative sentiment towards a word associated with warmth, relaxation, pleasantness and jolliness comes as a surprise. Although hygge resisted clear definition for years, different citizens in Denmark experience it differently. Historically, hygge became part of the Danish national culture in the nineteenth century, when Denmark lost most of its land to Germany, Sweden and Norway. The oneness and sameness expected in hygge is reflective of the Danish society.

Not a nation, but a tribe

Denmark's welfare state, combined with a convenient 37-hour working week, encourages hyggelig activities after a busy work day. Linguistics professor Carsten Levisen ties this to how important the sense of community is to the foundation of the Danish nation. "The Danes are not a nation… they are a tribe. This is the strength of their fellowship, and the reason that they have unshakeable trust in each other," he says. Susan explains that although she was born in Denmark, she has never been accepted as a Dane and has not really enjoyed hygge with them. She only experiences it with her family, and other Arabs.

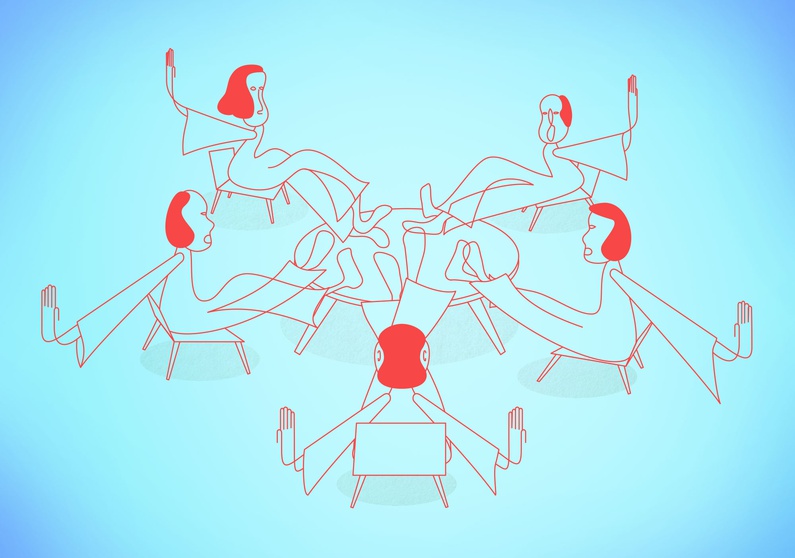

For a first-time immigrant, it is tempting to assume that the culture of hygge and its accompanying friendliness implies Danes are naturally accepting of strangers. This is not so. Hygge is both a repellant to minorities and immigrants and a suppressant to dissents. If hygge is essentially Danish and reserved only for insiders, it means that migrants and foreigners, especially those from non-western backgrounds, are shut out.

Hugette, a Burundian immigrant who has been living in Denmark for 24 years, also expressed her inability to integrate. "Hygge is very Danish. It's not just about eating together. It is a feeling that only Danes experience. I can’t [enjoy hygge with the Danes] because I always feel different but I do not let it bother me, every place has its culture and their style."

Cosiness to the extreme

Scholars have been examining hygge's use as weapon of social exclusion for years. Danish anthropologist Jeppe Trolle Linnet wrote that it "establishes its own hierarchy of attitudes, and implies a negative stereotyping of social groups who are perceived as unable to hygge." For Professor Daniel Grimley from Oxford University, the problem does not lie with the concept of hygge, but rather the way it has been appropriated now, particularly by western culture as a lifestyle choice. "It can potentially symbolise an insularity that swiftly becomes very bad," adds Grimley.

He thinks that Denmark has traditionally been very receptive to non-Danes, and it is only recently that the country has become more cautious and, in some ways, exclusive. This is of course a common problem, not just in Scandinavia but across Europe, and it connects to the current climate towards the refugee crisis, which makes countries across the continent accept harsher immigration policy and closed borders. Lotte Folke Kaarsholm, an editor of the Danish newspaper Information, told the Guardian in November last year, "Of course hygge excludes. The whole problem with Scandinavia is that these countries can only really work if you shut the borders."

This excluding characteristic of hygge is not surprising. It reflects the fiery xenophobic sentiments currently spreading across Scandinavia and beyond. What enforces the cultural homogeneity is the rules of hygge themselves; for instance, the rule of not having too many strangers in the room. "The impression of protected domestic space, and of turning inwards, can lead to hardened physical boundaries and political borders, especially if that space appears compromised or threatened," explains Grimley.

A peep into the extreme right-wing program of the Danish People’s Party (DPP) reveals their determination and obligation to protect Danish culture and heritage against the "onslaught of immigrants and foreigners." The prevailing sentiment of the DPP and their supporters is a disdain for foreign ideologies and values, who see them as a threat to their cultural values and communities. According to Thomas Dencker and Kevin Ramser of the NGO Humanity in Action, "the DPP has also become extremely controversial for its rhetoric and propaganda, which has helped to create the image of immigrants and Muslims as a uniquely dangerous threat facing Danish society and culture."

An anti-immigration stance is no longer the sole domain of far-right politicians - they're just screaming the loudest. Last year, Denmark passed a bill that empowered authorities to seize properties above $1,450 from asylum seekers in exchange for their upkeep in the country by the government. In August, the government cut social benefits to refugees and immigrants by 45%, in a move marketed as an "integration benefit." To get the message out, the government advertised this in a Lebanese newspaper so the word would spread even into the biggest refugee camps.

Censorship and taboo

This aversion to strangers stems from the fear that refugees and immigrants could destroy Denmark’s cultural heritage. However Nielsen, a co-organiser of the documentary house Doc Lounge, which provides documentary viewing in a hyggelig style, disagrees. "The hygge culture is all about coziness and a comfortable atmosphere for leisure which is why the candles, cakes, wines and flowers are important, it is not about race," she says. She does not think it encourages exclusion, but instead makes many international visitors feel relaxed and at home.

Yet, relaxation has its taboo. During hygge moments intellectual debates, controversial subjects and discussion of personal struggles are all censored. The perception is that discussion of these issues disturbs the relaxed mood inside the "feel-good cocoon." In her book Mirror, Shoulder, Signal, Dorthe Nors admits that while hygge is beautiful, it is also dangerous; with its goal of establishing consensus and avoiding any conflict or clash, as cultures inevitably will. For a foreigner, it might be difficult to feel cozy in an atmosphere where topics that relate to them the most are unwelcomed.

Siana Ivanova is a Bulgarian native who has been living in Aarhus, Denmark’s second largest city, for seven years. She admits that Danes do not feel the need to include more people in their lives, and hygge is a way of staying in their comfort zones. Siana came here for her university degree and decided to stay. To this day, besides her co-workers in a bar downtown, she has made only two Danish friends. "They are from my capoeira group, so there are not stereotypical Danes," she smiles, "They are already out of their comfort zones, engaging with Brazillian culture, so it was easier for me to enter their lives." Siana does not see it as a problem if Denmark is not very good at letting people in. "It is fine, but do not pretend that you are open welcoming society; it is contradictory," she concludes.

Back to the roots

Anti-immigration rhetoric is now brazenly touted by far right politicians, sparking debates on what "being Danish" now means. It used to be enough to contribute productively to the society to get a sense of identity and belonging. But now, apparently, it’s the bloodline that matters. "The attempt to assert 'real Danishness' can swiftly become exclusive. Somehow we need to move beyond the nation state and race paradigm, especially in the post-Brexit and post-Trump age," says Grimley.

Grimley calls for a new hygge, one with a more humane flavour. To him; that is where the word's proper ethnological meaning and value lies; not in soft candlelight and material comfort, but human kindness and compassion. "Hygge should involve the care and embrace of others, not only those closest to us. I think this is closer to its original meaning. And I’d rather that the spirit of tolerance and openness which characterised the Danish social model after the Second World War could be regained. It is what has made Denmark such a remarkable country in many respects," Grimley concludes. Only then can there be real hygge.