Uncertainty reigns after Non

Published on

In theory, France’s rejection of the constitution means that the project is now stillborn as all 25 member states need to ratify for it to become law. What does this mean for the other member states?

How can other governments ratify a treaty that has effectively been killed by the French? Will the governments of the Netherlands, Poland, the Czech Republic, Ireland, Denmark and, of course, the UK be able to secure the backing of their voters?

One bad apple spoiling the whole bunch?

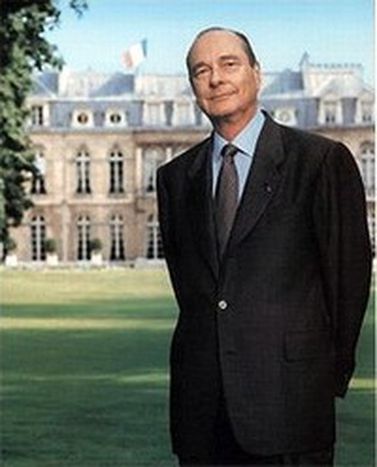

Obviously, the French No creates an institutional crisis for the EU, but it is unlikely that France will be forced to leave the European Union as the French President Jacques Chirac, rather ironically, suggested the UK would have to do in the case of a No last year. However, this does not detract from the fact that the Yes campaigns in other member states will undoubtedly be undermined by the French No. Even though several countries have already announced their intention to continue with the ratification process - presumably in the hope that if everyone else says Yes the French will be forced into thinking again - that France, the founding member and driving force of the European Union, could say No does not bode well for future referenda. Another knock-on effect extends to those countries who are eagerly waiting to join the EU club, as one of the reasons for the rejection of the constitution is that the referendum also acted as a plebiscite on other issues; namely further enlargement to include Turkey.

Did the UK want the Non?

So what about the constitution’s chances in the UK, the most sceptic of all the European nations? The absence of Europe as a campaign issue in the recent UK general election belies its ability to shape British politics. Tony Blair, Britain’s Prime Minister, knows that the French result will have a huge impact on his efforts to ratify the constitution as he embarks on his third term in government. Moreover, it will be Britain who has to pick up the pieces as the French rejection will be first in the in-tray when it assumes the EU presidency in July. But most commentators agree that Tony Blair was praying for exactly this result. After all, when the treaty was first drafted, all eyes were on Britain, who it was assumed would be the most likely party-pooper as regards the constitution. Although he recently told reporters that Britain would have a referendum irrespective of the French result, it seems unlikely that the Prime Minister would press ahead with a risky vote in which he would have nothing to gain. In this respect, the French No has taken the heat off the British referendum, a grim prospect for an already weakened Blair, allowing him more time and scope to focus on domestic issues, like re-engaging in the reform of public services.

On the other hand, it will be much harder for the British EU presidency to drive through the economically liberal agenda it wants, as many of those who voted against the constitution in France did so because of its ‘liberal’ nature. Indeed, the French President may well end up blaming Britain’s Anglo-Saxon ideas for his own humiliating defeat. There is a feeling that Chirac’s response could be the creation of a multi-tiered Europe. In France, the notion of a European "hardcore" consisting, perhaps, of the six founding members (Belgium, France, Germany, Italy, Luxembourg and the Netherlands) and Spain, has been gaining currency in tandem with a perceived decline in French influence in Brussels. Moreover, it seems that it is not just France which is entertaining this idea. According to the International Herald Tribune, German Chancellor Gerhard Schröder had already drawn up a provisional “plan B” in anticipation of a British No in which a smaller, tighter circle of members would operate together within the EU. Should this “inner circle” be realised, Britain could face isolation while other newer member states will be left feeling rejected; hardly the recipe for a strong and united Europe.

There are so many imponderables that make it far from clear what the definite consequences of the French No might be. What is certain, however, is that the European Union has suffered the greatest setback in its short history and it now faces a period of unprecedented uncertainty.