Ukrainian bohemia

Published on

Translation by:

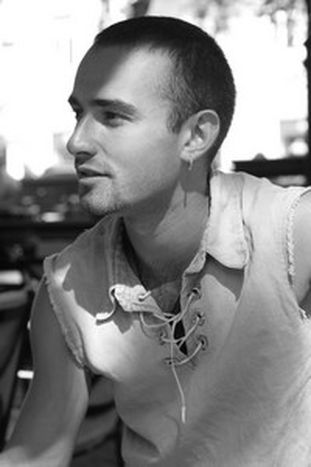

G. RingLeonid Kantier is a pragmatic troubadour. Both entrepreneur and actor, the Ukrainian has travelled all over the world with his wooden tabouret under his arm

It all began in 2003. Kantier, 25, and some friends went on a musical tour in the Lviv region west of the Ukraine. Within two weeks, they had travelled 200 kilometres and in each village they performed their sketches and traditional Ukrainian songs. Their tour ended on August 24, the day of the commemoration of the country’s independence. Three months later, Kiev was invaded by a sea of orange: the revolution had just begun and all the Ukrainians were singing on Independence Square.

The following year, Kantier started his first real tour, 'A tabouret as far as the ocean'. The idea, far-fetched as it may sound, was rather poetic: bringing a tabouret to see the sea. There were also shows based on old Ukrainian fairytales or classical plays. Together with some friends, Kantier, quickly packed his bags and headed to Poland, Germany and France. Penniless, and equipped with video cameras, cameras and microphones, the friends decided that hitchhiking was the best means of transport. India and Sri Lanka are next on the list. Soon, the tabouret will be able to see the China Sea and perhaps even Latin America.

A double life

‘When we arrive in a new town, I take my loudspeaker and scream: everyone living in this town, come and see...’ says Kantier. In France or Germany, street acrobats ask for money; in the poorest villages of Poland or the Ukraine, they prefer board and lodging. Having just started these travels, Kantier lives only for the possibility of journeying to the end of the Earth.

A cinema lecturer at a university but also director of the Lizard Studio production

company that he set up in 2000, this young single man leads a rather carefree lifestyle. His company is going well, and he could make a lot of money with a commercial or a musical clip in one go. ‘But I am learning more on by travelling during these few months, than I would have during a whole year in Kiev. OK, I am living like a homeless person, but it is a lot more interesting than making films or clips. Giving, receiving, sharing.’

This is a rather unconventional lifestyle in the Ukraine. Although there are several young Australians, Israelis or British people who go backpacking around the world for a few months or a year, in the Ukraine this is quite rare. ‘We are surprised that here, young people are afraid to leave. They have to work to eat, work to pay for an apartment. For them, we are a little like the new hippies,’ says Kantier with a reminiscent smile.

The drunkenness of freedom

Street theatre is very important to him. ‘In the theatre, people come to see you. You know what to expect, applause: strong or weak. The time where the audience dared to throw tomatoes at you or leave the theatre to criticise the performance or the directing has evolved. On the street, the rules are different. We don’t know who is coming or what the reactions will be.’ The street gives the actor a creative power that theatres no longer have; ‘Everything starts right at the beginning; you have to attract the attention of passers-by.’

Between acrobatics and mimes, the actor must catch the eye of the passer-by, “whether that is by cooking a traditional Ukrainian dish in the middle of a street wearing the native costume or by giving a reading of a national fairytale.’ What is important is not the gesture or the subject, ‘but the artistic performance that we put into the gestures that draws people’s attention.’

For each country visited, the nomad chooses themes that are in the news or ones about the mentality of the countries visited, be it ‘love between two workers in China’ or ‘war and exclusion in France’. Kantier has got his project translated on a large sheet. As soon as he can, he will ask an official organisation for its stamp ‘as a sign of support for our tabouret, that we will then use as a favour if needs be.’ On their visit to France, the troop was not allowed to play under the Eiffel Tower.

It would have taken more than that to stop them. Two guitars and a couple of bottles of wine later, sitting at the foot of the Iron Lady, the Ukrainian street artists are joined by a French guitarist, two Israelis, two Lebanese, two Russians, and so on.

These are ‘intense moments’, according to Léonid. The main thing is not that the public remember something about the Ukraine. ‘We couldn’t care less about that.’ But people should be left with an impression. ‘It took us some time to realise that ourselves. After we made our friends realise it, we wanted to make the whole world aware of it. So that it lives on… so that it is free.’

Translated from Bohême à l’ukrainienne