Ukraine and the language of geopolitics

Published on

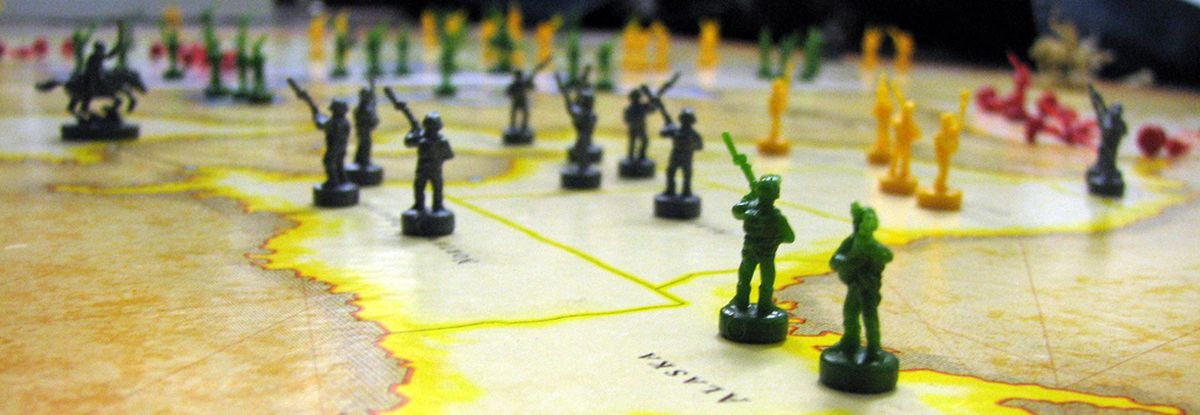

Kids often play the board game Risk. It is an easy way to get an idea of the way the world is divided, but with some interesting simplifications.

One of them ironically is that Ukraine on the Risk-map entirely covers European Russia. And in referring to this area when playing Risk, one would typically state ‘the Ukraine’.

But why is this significant?

In playing a game, this is innocent. But when discussing geopolitical affairs, if the article ‘the’ precedes Ukraine, one challenges the sovereignty of that country.

With the peace talks in Minsk on February 12th, the leaders of Russia, Ukraine, Germany and France seem to have succeeded in a first serious attempt to end the civil war in the Donbas. We can only wonder if the truce is going to last. The fighting around Delbatseve last week and the explosion that killed two people including a police officer in Kharkiv last Sunday revealed the fragility of the Minsk agreement.

Since the start of the Maidan Revolution in November 2013, the situation in Ukraine has been impressively unpredictable. What began as a protest against the corrupt Yanukovych government and in favour of a rapprochement with Europe, ended with an annexation of Crimea by Russia and a civil war in the East. Whatever the outcome of the latest round of peace talks, Putin’s abuse of the troubled situation of its neighbour makes clear that he does not respect Ukraine as a sovereign nation.

Since the start of the Maidan Revolution in November 2013, the situation in Ukraine has been impressively unpredictable. What began as a protest against the corrupt Yanukovych government and in favour of a rapprochement with Europe, ended with an annexation of Crimea by Russia and a civil war in the East. Whatever the outcome of the latest round of peace talks, Putin’s abuse of the troubled situation of its neighbour makes clear that he does not respect Ukraine as a sovereign nation.

Within these current circumstances, prefixing Ukraine with ‘the’ seems to be an insignificant issue. However, when digging a little deeper it has a huge symbolic value. It represents the biggest challenge Ukraine has faced since its independence in 1991: its recognition as an independent nation-state.

What's in a name?

Most linguists agree that the name ‘Ukraine’ comes from the Russian preposition ‘u’, which means ‘at’, and the Russian word ‘krai’, which denotes edge or border. A translation would therefore be ‘borderlands’ or ‘on the border’. This was previously used to describe the area at the southern border of Poland and Russia. Before 1991, when it still was part of the Soviet Union as the Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic, it was mostly referred to as ‘the Ukraine’. The same was once the case with former colonies, such as ‘the Lebanon’.

Officially, only two countries should be referred to with an article: the Bahamas and the Gambia. Still, there are some that can have an article without creating any semantic struggles for sovereignty: other group of islands for example, as the Philippines, or plural names, such as the United States or the Netherlands (although the Dutch refer to their country in the singular form ‘Nederland’). When we talk about areas within a country, as the northeast, we also need to use an article. The same logic was used for Ukraine when it was still part of the Soviet Union. Other Soviet States as Lithuania never had an article, as they once had been independent countries.

After the Ukrainian declaration of independence, the English language changed the official styling to ‘Ukraine’ thus recognising it as a sovereign country. However, since then the international community has often referred to it as ‘the Ukraine’ (even president Obama has been guilty of using this form until a year ago).

After the Ukrainian declaration of independence, the English language changed the official styling to ‘Ukraine’ thus recognising it as a sovereign country. However, since then the international community has often referred to it as ‘the Ukraine’ (even president Obama has been guilty of using this form until a year ago).

The use of the definite article is not entirely wrong, but it should only be used in the context of the historical non-bordered area. When we consider the Ukrainian nation, the use of the definite article undermines its sovereignty. It appears that we understand the importance of this nuance, and today most newspapers and world leaders stick to the form ‘Ukraine’.

Although Russian does not have articles, it has two important prepositions to indicate a location or a direction: ‘na’ and ‘v’. In general, the preposition ‘na’ is used to explain the location in a stretched area without a clear border. ‘V’ is applied when we talk about geographical or political areas that are officially bordered, such as countries or cities. So you would say ‘na Kavkaze’ to say ‘in the Caucasus’, and ‘v Rossii’ to say ‘in Russia’. With this distinction we can identify the problematic linguistic side of the conflict. Should we say ‘v Ukraine’, as a officially bordered state, or ‘na Ukraine’, as the stretched area at the south-western border of Russia it once was?

Post-independence

After Ukraine gained independence in 1991, it asked Russia to stop the use of ‘na Ukraine’ and start recognising it as an independent sovereign state by using the form ‘v’. However, all Russian media, both state-owned channels as Rossia 1 and independent newspapers as Slon, still use the form ‘na Ukraine’. This is in line with the official Russian literary norm, which argues that it is conforming to the linguistic and historical connotation as borderland.

For most Russians, this is not a conscious decision but a natural way. ‘I usually say ‘na Ukraine’, but not for political reasons,’ a young Muscovite Lyosha explains. ‘I use ‘na’ because it’s the literary norm; years and years of language-evolution has brought us to that norm.’

The choice of style becomes even more interesting when we consider the disputed areas.

The choice of style becomes even more interesting when we consider the disputed areas.

Should we speak of ‘Crimea’ or ‘the Crimea’? Both forms are used. In Russian one would say ‘v Krimu’. A peninsula or island normally has the preposition ‘na’. The Crimea is separated from the mainland and is therefore considered as an area with a clear border.

For the Donbas region, which consists of the revolting oblasts (ed. regions) of Donetsk and Lugansk, both forms are used. In English newspapers we find both ‘Donbas’ and ‘the Donbas’. In Russian, the official norm demands the use of the preposition ‘v’ because the name is an acronym of ‘Donetskiy bassein’ (the Donets Basin) and you would say ‘v basseine’. Still, there are both Russian and Ukrainian newspapers that use the preposition ‘na’.

‘When we talk about a country, for example Ukraine, we use the preposition ‘v’,’ an editor of one of the more important Ukrainian newspapers, the Korrespondent, explains. ‘However, when we talk about a region within a country, as Kuban or Donbas, which are not countries of their own, we use the preposition ‘na’.’

For a lot of Ukrainians, ‘na Ukraine’ means that their country is not considered an independent nation-state. It would be to talk about Sudan as ‘the Sudan’ because it originally referrers to a desert, or to speak of ‘the Congo’ as if it still would be just the land that surrounds the Congo river.

Obviously, president Putin uses the official Russian styling, which inevitably has a political connotation. ‘Russia deliberately uses the preposition ‘na’ because it still considers Ukraine a region, and not a country,’ the same Korrespondent editor stated. Putin did indeed repeatedly indicate at different press conferences that he does not recognise Ukraine as a sovereign nation-state.

For him, it still is the wrongdoing of the bolshevists that created the Soviet Republic during the civil war from 1917 to 1922. And he is willing to go as far as needed to make up for this ‘wrongdoing’. With the annexation of the Crimea and the revolt in the east, Russia has been pretty successful in reducing Ukraine to the simple borderlands it once was.

For him, it still is the wrongdoing of the bolshevists that created the Soviet Republic during the civil war from 1917 to 1922. And he is willing to go as far as needed to make up for this ‘wrongdoing’. With the annexation of the Crimea and the revolt in the east, Russia has been pretty successful in reducing Ukraine to the simple borderlands it once was.

Putin’s policies since the Maidan Revolution have inspired a lot of new jokes about the Russian head of state. One of them goes: ‘Vladimir Vladimirovitch, will there be an “Iron Curtain” again? ‘No! A regular barbed wire will do.’

With Europe’s impuissance in stopping Russia’s annexation of the Crimea and today’s military support of the Donbas region, the very sovereignty of Ukraine is at stake. The English language has finally gotten rid of the definite article.

For Putin, however, it still is the Ukraine.