Typically Italian elections in April

Published on

Translation by:

Sarah GrayOn 13 and 14 April the Italians go to the polls under an electoral law that no-one is happy with. Majority rule or proportional representation? A two percent or four percent cut-off clause? What is the best solution for Italy?

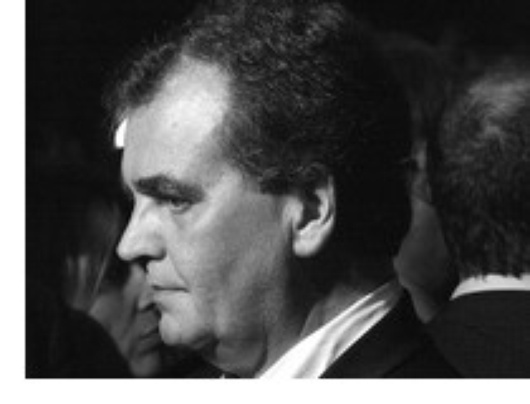

Electoral reform has been one of the most difficult issues of the second Italian Republic, in place since the corruption scandals of the early nineties. Often cited as the only way to overcome the ‘evils’ of the political system, electoral law has been changed twice in the past fifteen years, both times following a referendum. A third popular vote is planned for 2009 in order to change the law currently in force, which was approved by Berlusconi’s government in 2005. At the time Berlusconi’s colleague Roberto Calderoli, then minister for reform, called the law ‘an obscenity created to cause both the left and the right difficulties’ in their relationship with the electorate.

Italians in search of a two-party system

Any self-respecting Italian politician today has been eclectic in their views on the electoral system, moving from an admiration for the French system of two rounds of voting, to a fascination with the German model of proportional representation, with an interest in the regional voting system of Spain. The truth is that Italy, as always, not knowing what to do and not wanting to make a choice, has ended up with a typically Italian, complicated electoral system.

Any self-respecting Italian politician today has been eclectic in their views on the electoral system, moving from an admiration for the French system of two rounds of voting, to a fascination with the German model of proportional representation, with an interest in the regional voting system of Spain. The truth is that Italy, as always, not knowing what to do and not wanting to make a choice, has ended up with a typically Italian, complicated electoral system.

After half a century of proportional representation, a 1993 referendum moved Italy to the majority rule system. The Italian parliament somewhat timidly chose to make the change gradually, leading to an electoral law all’italiana – following a general structure of majority rule, yet with an element of nostalgia for the former system. Under the law twenty five percent of parliamentary seats in both houses were won using proportional representation.

The objective of this first reform was to reduce the number of political parties in the Italian parliament and move towards a two-party system. This, however, was not the case. After years of praise for the majority rule system which did, for better or worse, guarantee the country something like a two-party system, in 2005 Italy dramatically returned to classic proportional representation. This includes a clause that any party has to obtain four percent of the vote in order to win seats, although the cut-off is only an easily obtainable two percent for any party, however small, in alliance with another party having passed the four percent mark.

One of the most criticised aspects of the system is the way in which the upper house, the Italian senate, is elected. Seats in the senate are allocated based on regional votes. This can therefore lead to the paradoxical situation where two different parties have the majority in each chamber. Another important change made by Berlusconi’s electoral law is that voters can no longer choose their MP; instead they choose the party, and the party choose which candidate is to take each seat won.

The first test of the new law, the 2006 general elections under Prodi’s government, ended in disaster, with a political system divided to such an extent that no-one could govern. Despite this, parliament did not vote for a new electoral law and Italians will now return to the polling booths with a system that many judge to be even worse ever. With a certain boomerang effect, the law approved in haste three years ago by Berlusconi’s centre-right government to make life more difficult for Prodi could now backfire and damage their own efforts in the April elections, although Berlusconi is currently favourite to win.

Mamma mia! So many parties

The current election campaign has seen certain potentially suicidal choices by Italian parties, considering the current electoral system. After winning in 2006 with a majority of only 24 000, the centre-left has now split into two main groups. Former mayor of Rome Walter Veltroni’s Partito Democratico is allied with the Radicals and the Italia dei Valori group, but no longer with the Sinistra Arcobaleno union (which includes the Rifondazione Comunista, Comunisti Italiani and the Greens). The latter obtained a respectable ten percent of votes in the last elections. The Catholic centrist party UDC was an ally of Berlusconi in 1993 but has now left his centre-right alliance to stand alone, with their own candidate for prime minister, Pier Ferdinando Casini. What chance do these smaller parties have under a system that favours the larger alliances? None at all. So what then?

It almost seems that many political players, rather than preparing for government, are preparing for the lack of government, that is to say they are aiming to hold as much sway as possible in the (inevitable) talks to attempt to form a new government. It may seem like political fiction - but anything is possible in Italy.

Europe's political systems

Click on the icons to find out more about the electoral systems in other European countries. To find out how it works in the EU, click on the watermelon

Google map by Marco Riciputi

In-text photo: ex-minister Calderoli (ZioDave/ Flickr), homepage: Italian rage (Jaume D'Urgell/ Flickr)

Translated from Elezioni italiane: un “porcellum” in Europa