Turkey's Nobler Blood

Published on

As Turkey celebrates its 86th birthday, the walls between Turks and Kurds have begun coming down. A relationship once regarded as “active human rights abuse” is slowly becoming “hesitant disregard” and may one day even grow into “begrudging tolerance. ” On October 29th, 1923 Turks all got together and figured they needed to tear down old walls by establishing a republic.

Some walls were mundane (replacing fezzes with fedoras to blur distinctions between Westerner and Turk), others more explosive (ending arbitrary monarchy, citizens now picked their own leadership as long as it was the one party allowed to run in elections) and a few walls were just downright sexy (you could now see women’s ankles !).

On Thursday Turks celebrated the 86th anniversary of this transformation by lining the streets with flags, lighting the sky with fireworks and listening to military bands play patriotic tunes. People’s love for the republic almost matched the joy of not having work on a weekday.

The only people who didn’t have the national holiday off

The only people who didn’t have the national holiday off

But Republic Day is not just about Turkish modernity or even ankle-appreciation, it is also a celebration of ‘Turkishness, ’a hard-to-define phrase, like mojo, that sounds like fun but keeps getting you in trouble.

The young secular republic promoted a monolithic sense of Turkish national identity ; all citizens were expected to ‘go Turkish’and nationalistic phrases such as “happy is one who calls himself a Turk” flourished. Recently denounced by the Council of Europe as “ethnic discrimination, ” the happy Turk line still comes off clean compared to the nationalistic slogans of today which string together zealous jargon in an effort to out-macho the sign next to you.

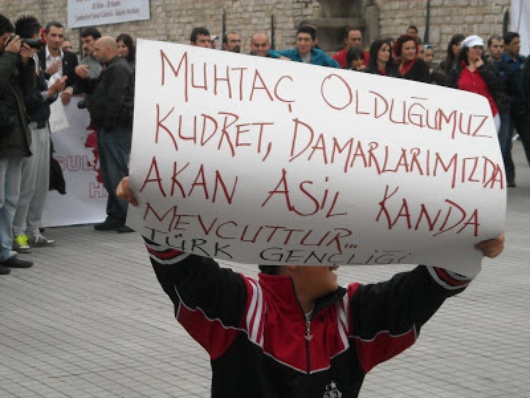

A child holds up a very manly “The strength we need is in the noble blood that runs through our veins… ” If someone ever manages to convey Turkish pride in a series of manly grunts, they will become our next President.

A child holds up a very manly “The strength we need is in the noble blood that runs through our veins… ” If someone ever manages to convey Turkish pride in a series of manly grunts, they will become our next President.

With all this Turkish trumpeteering, a new wall was erected between those who assimilated and those who refused. Being a Turk meant being integrated into the republic ; all ethnicities were welcome as long as their own culture stayed at home. But this “publicly Turkish, privately something else” policy hit a snag with the issue of Kurdishness.

The Kurds are Turkey’s largest minority, making up 20 percent of the population and about 72 percent of all the press we get in the West. Between a different language, a distinct culture and a war waged against the Turkish government since 1984 by the separatist Kurdistan Workers’Party (PKK), Kurds have consistently underachieved at assimilating.

Yet even that wall has been showing cracks : over the past year the government has been pushing a democratic initiative to enfranchise the Kurds. Even the biggest obstacle, the PKK, has been a part of the initiative and just last week Kurds were out on the streets celebrating Kurdishness over 34 PKK members returning to Turkey and submitting to authorities as a symbolic gesture of rapprochement.

But many Turkish people were not pleased…

Turks standing next to a sign that reads “Traitors will not be forgiven on this soil watered with the blood of our martyrs, ” which is disapproval of either of the government’s policy of reconciliation or its horrifying agricultural policy.

Turks standing next to a sign that reads “Traitors will not be forgiven on this soil watered with the blood of our martyrs, ” which is disapproval of either of the government’s policy of reconciliation or its horrifying agricultural policy.

As Turkish democracy matures, it becomes more comfortable with cosmopolitanism, though some will always resist. Like Chief of General Staff Ilker Basbug’s Republic Day warning, “the Turkish Armed Forces will rise as a steel wall against any attempt to compromise the Turkish Republic’s indivisibility and its national unity. ”

He can’t help it, he just has too much noble blood in him.