Turkey, at the heart of the Kurdish question

Published on

Translation by:

ruth ahmedzai

ruth ahmedzai

Turkish Prime Minister Erdogan has just called for a political solution to the “Kurdish problem” – essential if negotiations for accession to the EU are to succeed. From Kurdistan, Ulrich Schwerin reports.

The Officer roars out his commands as a parade of soldiers streams through the street, the band churning out a melancholy marching song. Even in Diyarbakr, a Kurdish stronghold in south-eastern Turkey, the Turkish Republic is celebrating the anniversary of its victory in the Greco-Turkish War on August 30, 1922. On the platform where the families of officers and local nobility sit, children are squirming uncomfortably in their seats. A few hundred people are standing at the sides of the road, clapping and waving flags as another unit marches by, but behind the black basalt walls of the old town, life goes on as usual.

Kurds sidelined

“It might be a national holiday, but all the banks and government buildings stay open. It’s the same every year and nobody’s interested in it,” says Mehmet, who is sitting on a shop doorstep, drinking tea. “The army celebrates its victory in the War of Independence and the creation of the Turkish Republic, but for us Kurds it symbolises the end of the dream of our own state.”

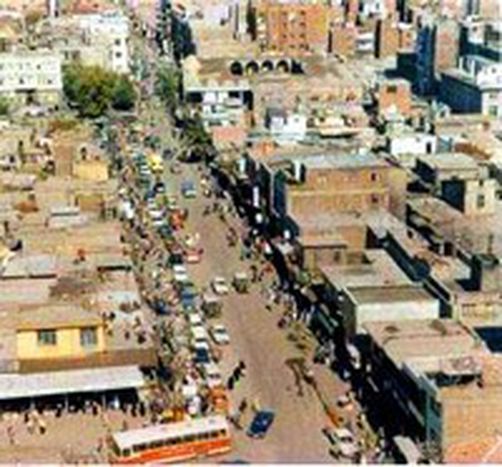

It was with this dream in mind that the Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK) took up arms in 1978. The conflict assumed war-like proportions in the early nineties when the Turkish army began its ‘scorched earth’ policy in response to the guerrilla attacks. It had some success, but led to the annihilation of countless villages whose residents fled to Diyarbakr. The town’s population now exceeds a million.

Erdogan admits problem

“The PKK used to campaign here in the town too, but then people had enough of it so they’ve gone back to the mountains,” says Hassan, owner of a carpet shop in the courtyard of an old caravanserai. “It’s calmed down now, but business is still bad. There aren’t enough tourists coming. The PKK announced a month-long ceasefire last week. I hope it lasts…”

It was after a speech by Turkish Prime Minister Recep Tayyip Erdogan that the PKK reinstated the ceasefire which they had revoked in June 2004. While visiting Diyarbakr, the head of state had said that the Kurdish problem could only be solved by political means. This constituted at once a rejection of the military’s calls for harsher measures in the fight against terrorism and the first admission of the existence of a “Kurdish problem”. Until this point, the government had always considered it a military or economic issue.

Third generation mobile phones

Although Erdogan’s comments were met with objections and protest from nationalists who fear direct negotiations with the PKK, the army remains muted in its reaction. Its restraint suggests the view that bringing the military back into the conflict a month before the start of accession negotiations with the EU would cast the wrong impression, perhaps also the calculated view that an intensification of the struggle would only benefit the PKK. In a military struggle, the PKK sets itself up as the representative and defender of the Kurds, a realisation which led them to re-arm in June 2004, though the movement failed to reclaim its former significance. The renewed ceasefire is above all an expression of their helplessness.

Most Kurds are no longer prepared to support the PKK’s strategy of violence, not least because the government’s efforts at development have begun to bear fruit and the region has changed radically since the start of the conflict. “Fifteen years ago, people only went to shops to buy tea and sugar. Now every town has a supermarket. My first photo was from my first day of school and my dad was the only one in the district to have a camera. Now everyone’s got one,” says Mehmet, pointing to his third generation mobile.

It is widely recognised that further development depends on lasting peace. “Tourism will only increase if it stays calm in the future,” says Hassan, “then more people will come here and buy beautiful Kurdish kilims [rugs], and our business will flourish.”

Translated from Die türkische Kurdenfrage