A History in Letters: German Migrants in America

Created on

Translation by:

Eleanor Cooke

Eleanor Cooke

Article in en

In the 19th and 20th centuries, millions of Germans crossed the Atlantic Ocean to start a life in the New World. According to various censuses, over 43 million American citizens have German roots. However, very little is known about their ancestors’ stories. Historians are now working with citizens to develop a better understanding of these people’s everyday lives. This article is the first in our new series, “Terrains Communs” (Common Ground).

Here’s a tip for when you next spend time in New York: get up early, head to the Battery at the southern tip of Manhattan Island and get on a ferry to Ellis Island.

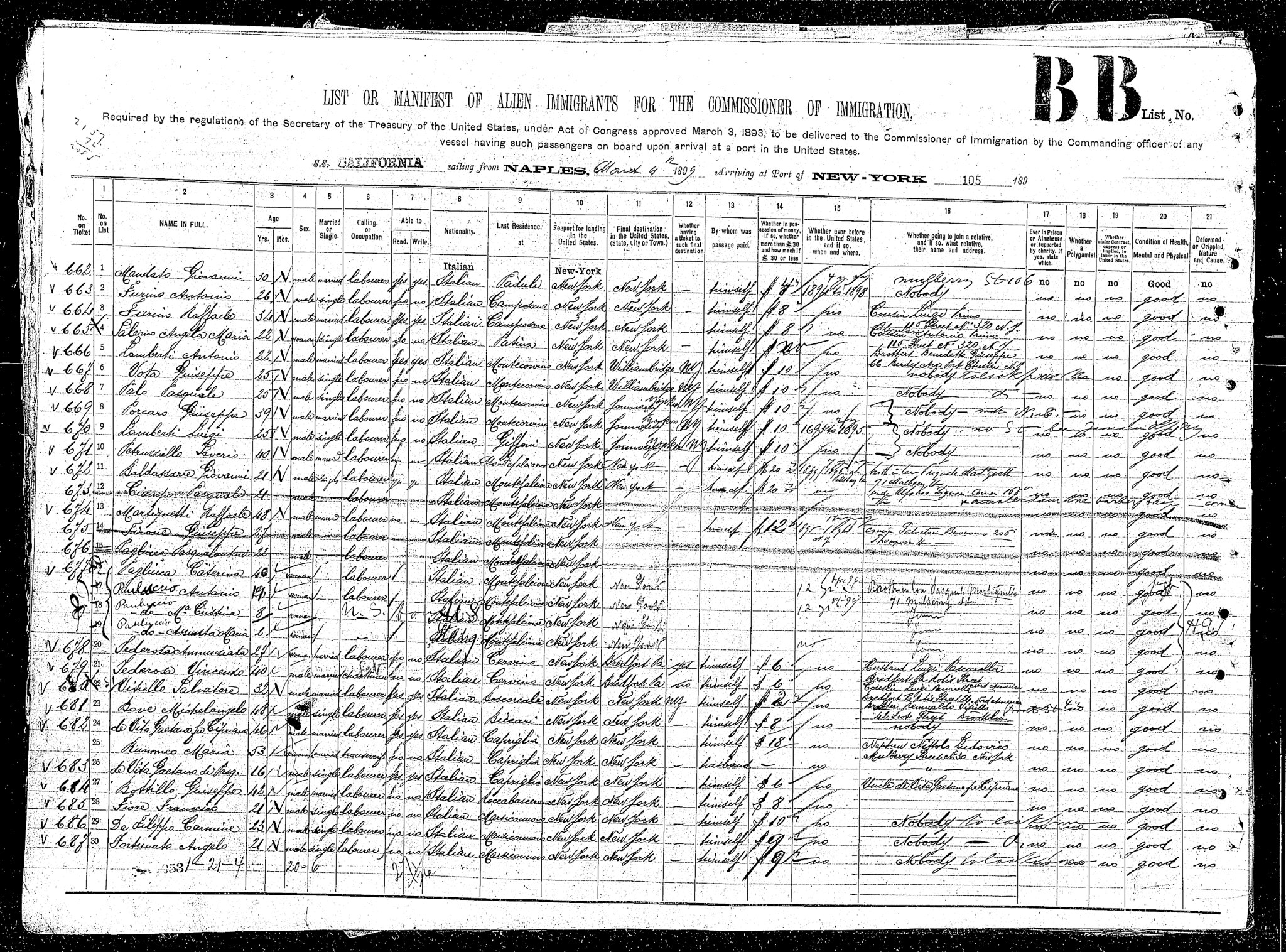

From 1892 to 1954, this island played host to one of the United States federal government’s main immigration centres. Over 14 million people first stepped down onto US soil on this very island. Getting to this island was the start of the American Dream.

Ellis Island is now a museum, quite unlike any other... Every day, dozens of American families scour its registers and other documents from its archives. What do they hope to find? Traces of their ancestors, who often arrived with only a small bundle of possessions to their name.

Treasured Letters

People of all ages, genders, ethnicities and nationalities travelled across the Atlantic to experience a new way of life - the American Dream. With many men and women travelling alone to make a new life for themselves, seeking out an economic climate that offered better opportunities for themselves and their families, migrants often wanted to maintain a close bond with the loved ones they had left behind in Europe.

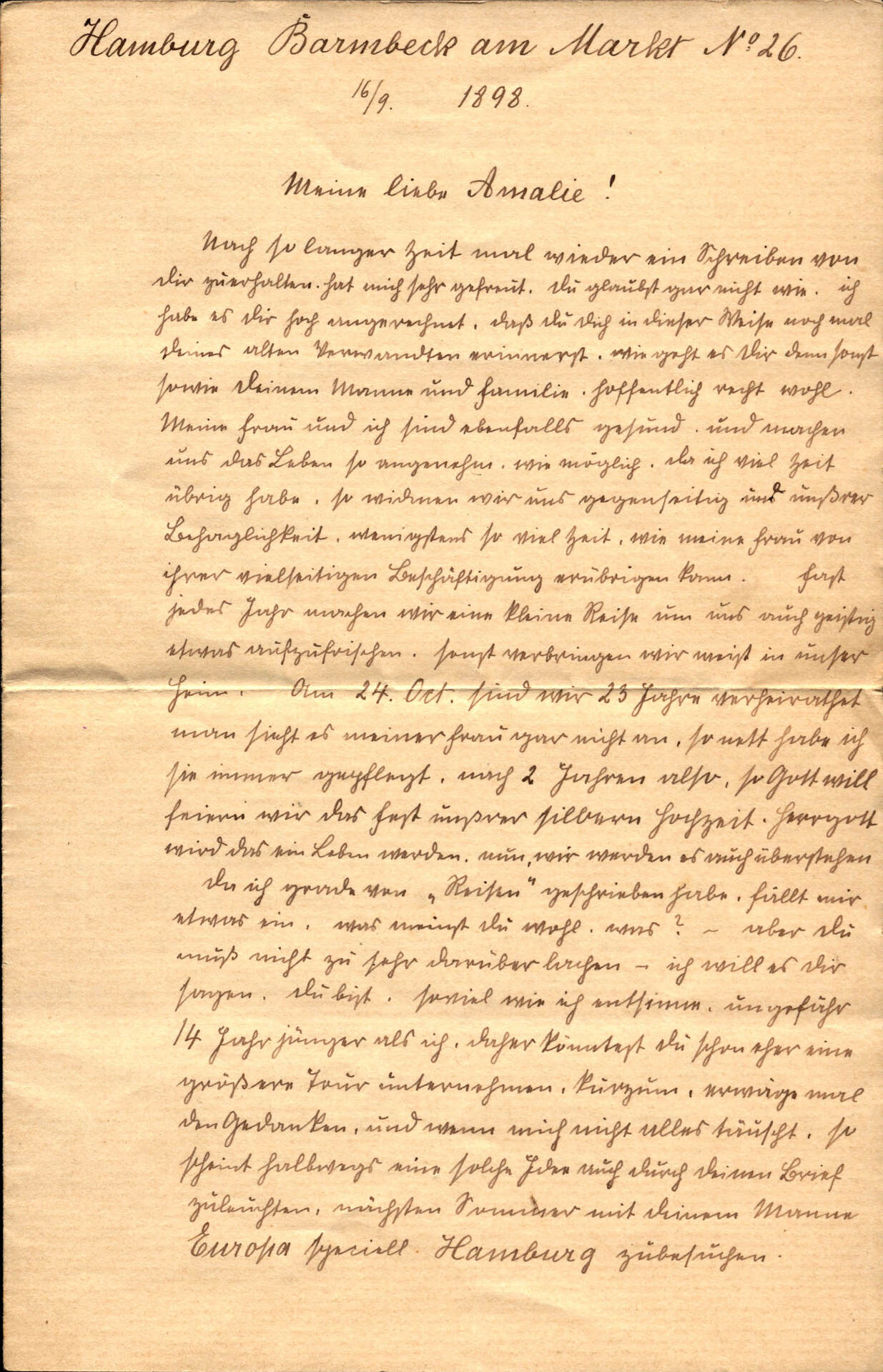

Literacy was on the rise in the 19th century, which meant that letter writing was no longer exclusive to the elite. This meant that some families were able to write to one another over many years. The letters that remain from this correspondence are treasured by the writer’s children or grandchildren.

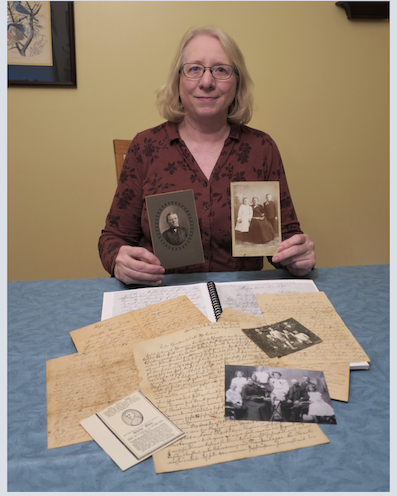

These letters are a goldmine of information, explains Jana Keck, a doctor at the German Historical Institute working on the COESO pilot study Growing Migrant Knowledge: Contemporary and Historical Perspectives.

This research project involves the study and digitisation of 3,000 letters exchanged between German immigrants in the United States and their family and friends in Europe, which shed new light on the lives of migrants in the United States.

These letters, which come from the personal archives of American families, have been transcribed, translated and published.

They provide a better understanding of daily life in this specific context, for those living in the US and those who stayed behind in Germany.

“These letters are extremely precious to us as [they allow us] to learn more about the lives of people in Germany and the lives of those who emigrated,” adds Jana Keck. These documents often show how emigrants perceived their new lives, but they also include economic information such as the price of livestock or eggs.

Far from the Gatsby-esque success stories of European emigrants who made their fortune across the Atlantic, these letters reveal how ordinary people felt living outside their home country, separated from their families and culture, keen to be kept informed of marriages, births and deaths.

Sunday Historians

What makes this citizen science project unique is its participatory approach. On both sides of the Atlantic, Americans and Germans have contributed letters from their personal archives, helped to decipher their contents, and been trained to digitise or translate them. The transcription of these letters was simplified by the open-source software Transkribus.

In Germany, participants were mainly teachers and history students who saw the project as a “hobby” according to Jana Keck. However, some Americans joined the project for reasons much closer to their hearts.

“They are proud to own letters of such historical importance!” says the researcher.

“At first, they didn't think that their grandmothers or grandfathers could be called real heroes, as they didn't do anything special in their lifetime. We disagree! In fact, those who were brave enough to cross the Atlantic, facing an uncertain future, fully deserve their place in our history books!”

The people exploring their own historical background can be compared to what the French historian Philippe Ariès called “Sunday Historians”. Men and women who are passionate about the past can contribute to historical research, without being professional historians.

Delving into the Past

These epistolary archives also give new insights on how societies have evolved over the years. These letters mention the key political events of the 19th century. They tell us that German-speaking people who emigrated to the United States developed a ‘German identity’ even though Germany was not yet an officially unified country, with most Germans primarily identifying by the region they came from [editor’s note: Germany became a country with the same status as France or the United Kingdom in 1870, after the Franco-Prussian War]. Some were abolitionists at the time of the American Civil War, while some were already showing signs of anti-Semitism.

A significant number of the letters studied in this research project were exchanged between women. Some of them were also written by children, to help them to practise their writing. These letters were carefully and studiously written as at that time, paper, ink and stamps were still very expensive. Writing to an aunt or uncle in the United States became an evening task for children in German families.

“Writing really became a family activity,” explains the historian.

This correspondence also provides us with unique accounts written by female migrants. “Towards the end of the century [editor’s note: the 19th], many women emigrated because they could not find work in Germany, and they found work in cities, as servants, for example. But they already had their own apartments and were quite independent” … unlike their sisters and cousins who stayed behind in Europe.

On the whole, these letters show that the women who stayed in Germany were less progressive when it came to women’s rights but, according to Jana Keck, they “were fascinated” by women’s independence in America. “They didn't talk about it publicly, but hearing from their sisters who left the country, who were making their own money and were truly independent, must have had a strong impact on these women.”

Their correspondence also reveals another key aspect: the act of migrating, leaving home, crossing oceans has an irreversible effect. The German community, unlike other immigrant groups, integrated very quickly into American culture. Their surnames were Americanised. Their family ties and their friendships became strained or fizzled out. The children of migrants did not speak German. And so, the letters stopped.

Germany Reconsiders the Issue of Dual Citizenship

This project, a pilot study in COESO, is set to continue. More research into epistolary correspondence is planned in the United States. In Germany, the focus will be on providing training in schools on how to use digital tools.

These transatlantic genealogical research projects have not yet revealed all their secrets. They aim to respond to an almost visceral need in many Americans. The most obvious example of this is the trend for DNA testing, which make it possible to trace back your roots for a reasonable price, with just a few drops of saliva.

If Americans have held onto family documents and other original papers, they can even apply for citizenship in their ancestors’ country of origin. Italy, Poland, Spain, the Czech Republic, Norway, and Slovakia have all put in place naturalisation schemes for applicants that can prove the origin of their ancestors (birth certificates, baptism or marriage records).

There are even specialised companies such as Luxcitizenship, founded by Daniel Atz, an American-Luxemburger, which can be called upon to manage these applications.

What about Americans who wish to become German citizens? A new law on naturalisation and citizenship is set to be examined in spring 2023 at the Bundestag, or German parliament. This change could simplify access to dual citizenship by shaping the law to a new reality: Germany no longer deals primarily with emigration, but with immigration. At the present time, only Jewish emigrants whose nationality was revoked by the Nazi regime before the Second World War can obtain a German passport while retaining their American citizenship.

—

This project was organised in collaboration with the COESO research project (Collaborative Engagement on Societal Issues), combining social sciences and participatory research. Coordinated by [the École des Hautes Études en Sciences Sociales, orSchool of Advanced Studies in the Social Sciences] (https://www.ehess.fr/fr), COESO is funded by the research programme Horizon 2020. The content of this article may not under any circumstances be considered as reflecting the position of the European Commission, which may not be held responsible for the information it contains.

Image: Poster for the Cunard Line, 1875. © George H. Fergus, Chicago,1874 (original copyright) — U.S. Library of Congress

Translated from D’une lettre à l’autre, des égo-histoires d’exils by Eleanor Cooke .