Tourist joys and locals' struggles in Malaga

Published on

Cross-posted from DaivaRepeckaite.com - feel free to comment the post there! Malaga, in South Spain, on the Mediterranean cost, turns out to be a particularly attractive place to settle for all kinds of people, especially Germans looking for a nice place to retire. But, according to my friend there, people from all over Spain say they would choose it as a place to live.

It was the first city I visited in Spain, and I think I know now why Spain appeals to so many people in my life. Malaga has it all: the sea and mountains, cultural life and comfortable, walkable city spaces.

I set out to explore it with a local, my friend Jose. The story of Malaga starts my first real Spanish tapas:

Tapas are ubiquitous in Spain – in many places they come with a drink

by default. The one you see above is called ‘Russian salad’. It is the

way of presenting the food, not the content, that makes them

unmistakably Spanish. But if you want an example of food globalisation,

here it is: this mix is called ‘Russian salad’ in Mediterranean

countries, ‘white salad’ in Lithuanian and ‘Olivier’s salad’ (because

invented by a French cook) in Russia.

Tapas are ubiquitous in Spain – in many places they come with a drink

by default. The one you see above is called ‘Russian salad’. It is the

way of presenting the food, not the content, that makes them

unmistakably Spanish. But if you want an example of food globalisation,

here it is: this mix is called ‘Russian salad’ in Mediterranean

countries, ‘white salad’ in Lithuanian and ‘Olivier’s salad’ (because

invented by a French cook) in Russia.

Next, I learn that creative locals have given names to coffee-to-milk ratios in their beloved cafe con leche. You can order a ‘half’, a ‘shade’ and a ‘cloud’ – this is specific to Granada and sounds funny everywhere else.

Cafes in Malaga also take pride in offering very fresh boquerones (a kind of small fish), which you eat with lemon. The gastronomic journey continues in a Cuban restaurant, which offers tapas with strange names and the best mojitos I’ve ever had.

Malaga matches most people’s impression of Spain so exactly that you may think you are in a movie. Many people sit outside enjoying a coffee and discussing something as loud as you would expect Mediterranean people to speak. Much of the town closes for siesta. A road sweeper, who looks like young Woody Allen, slowly, with a cigarette between his teeth, prepares the street for the joys of the evening. A salesperson at a second-hand shop winks when saying hello. Pleople like saying hello to each other, and it is a good idea to memorise everyone, because you never know whom you will need one day.

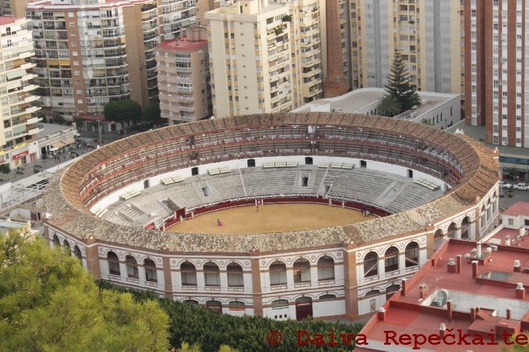

And yes, people are really practicing for corrida in this photo:

Locals believe there is not much to see in Malaga, and most tourists

actually visit many different cities in South Spain, staying for only a

couple of days in each. In Malaga, it’s mostly the sea and the sights

that attract travellers.

Locals believe there is not much to see in Malaga, and most tourists

actually visit many different cities in South Spain, staying for only a

couple of days in each. In Malaga, it’s mostly the sea and the sights

that attract travellers.

Of course, every northern eye rejoices at the sight of oranges hanging from the trees – very sour though, I tried

As we explore various neighbourhoods, Jose repeatedly mentions: this one used to be dangerous. Why did so many places ‘upscaled’ in the recent years? More involvement of local authorities was crucial. Better infrastructure, more police and many renovations appeared to be quite effective. At the local level, political parties are more practically oriented, leaving behind the usual squabble of national politics. In the past years Malaga’s standard of living has improved, and the airport is being continuously upgraded to bring in more tourists. Even if they stop by on the way to Granada. With upcoming elections, the local government does its best to show off. Even lighting up this building in the expected winner’s colours (my friend says it’s not typical and immediately connects it to the elections this weekend)…

Some other points worth noting are Malaga Contemporary Art Centre

and the Picasso museum. The former had an exhibition of mega-large

photos of the surface of Mars, edited by a German artist. While some of

them were interesting, there was too much white space between them, thus

failing to create an impression of being surrounded by this Martian

surface, which, it seems, was the purpose. Yet the permanent exhibition

is much more interesting, including several abstract paintings and a

slow-motion video interpretation of Delacroix, where Liberty trips,

falls down and is beaten up by the men who follow her. The museum’s shop

sells the most creative souvenirs you can think of. We also visited

archeological ruins belonging to the university. The building also

hosted an exhibition of art students. The Picasso museum is home to some

relatively unknown works and is capitalising on the fact that the

renowned artist lived in Malaga for some time.

Some other points worth noting are Malaga Contemporary Art Centre

and the Picasso museum. The former had an exhibition of mega-large

photos of the surface of Mars, edited by a German artist. While some of

them were interesting, there was too much white space between them, thus

failing to create an impression of being surrounded by this Martian

surface, which, it seems, was the purpose. Yet the permanent exhibition

is much more interesting, including several abstract paintings and a

slow-motion video interpretation of Delacroix, where Liberty trips,

falls down and is beaten up by the men who follow her. The museum’s shop

sells the most creative souvenirs you can think of. We also visited

archeological ruins belonging to the university. The building also

hosted an exhibition of art students. The Picasso museum is home to some

relatively unknown works and is capitalising on the fact that the

renowned artist lived in Malaga for some time.

With all the nature, culture and easy access to Spain’s other cities, you can’t wonder why many people want to live or at least retire here. But the picture is rosy only for tourists and the privileged. With unemployment rate of 23%, and youth unemployment at 48%, Spain is tense and prepared for a social explosion. As I munch on a huge patata asada (roasted potato with corn, cheese and vegetable filling), I listen to young Spanish graduates and students active in youth voluntary work discuss their ideas for the nearest future. Trapped among multiple unpaid internships, unable to afford living in another city, young people in Spain are extremely dependent on their families. They are creative, skilled and enthusiastic, and they know there is a demand for their work, but nobody seems to care. The market is unable to mediate between these people and those who would benefit from their skills and engagement. There is a need for quality press, and there are many unemployed journalists. There is a need for social work, and there are many people who would be willing to do it, if only they could make at least a minimal living. No wonder why many young people have enthusiastically joined the so-called indignados, who are fed up with cosmetical reforms and want a system change. But before change comes, the youth increasingly looks beyond national borders for solutions. Medium-skilled and unskilled workers these days choose Brazil. Many Latin Americans leave for their countries. Highly educated Spaniards’s eyes are increasingly fixed on Brussels. Even if jobs are scarse, various learning, internship and paid volunteering opportunities mitigate the frustrating situation.

Yet others take difficult test to join the ranks of public servants, even though, as everywhere, public sector cuts are strangling its workers. The police sounds as an attractive option. Time will show how the newly recruited officers will feel when they have to deal with their friends in the indignados movement.

The situation in Spain, albeit not as extreme, somehow reminds me of Egypt. With the country’s dependence on tourism and shipping, the population is urbanised, ‘traditional’ lifestyles are not sustainable anymore, but the modern consumerist paradise that young people see on TV and the internet is nowhere near them. There are many fake jobs, which are basically unnecessary paper shuffling, just to keep more population employed. There is no interest whatsoever to take advantage of modern technologies when labour is so cheap.

It is far from true that, as stereotypes suggest, Spanish workers are lazy. They work more hours than their French, Swedish or German counterparts – those who have jobs, that is. Again, the situation prompts people to look at the in-built system features: how is it that some people are struggling to make meaningful use of their skills to no avail, while others are exhausted from huge workloads? This is the side of Spanish reality that is hidden from all the romantic images, something that tourists don’t see. And the continuous reproduction of the stereotype of lazy Southern Europeans directly translates into everyday realities: these countries are seen by many as suited for romantic dreams, admiration and retirement, but not for working together or investment.

It is expected that the right-wing will sweep the elections, bringing more budget cuts and nobody knows what. But for most people reshuffling in seats among the main political parties is not the change they want. How do they work for the change – wait for the next post