Tourism amid Terrorism: A mini-break in Istanbul

Published on

In a year of devastating terrorist attacks, Istanbul stands out as possibly the most dangerous city in Europe. Over 140 people were killed in five major attacks; not to mention the attempted coup d’état by Turkey’s armed forces. But that hasn't stopped some tourists from trying to explore the ancient city.

I’m not a thrillseeker. I booked my flights in early July, just before the coup. Istanbul had long been on my bucket list, and although the UK had advised against all travel to Turkey’s border with Syria, Istanbul lies over 1,000km to the west. It wasn’t until the night before my arrival, sat in the antiseptic surroundings of Qatar's Doha Airport, that I heard the terrible news that suicide bomber and car bomb had targeted police outside Beşiktaş’ Vodafone Arena stadium, killing 44 people.

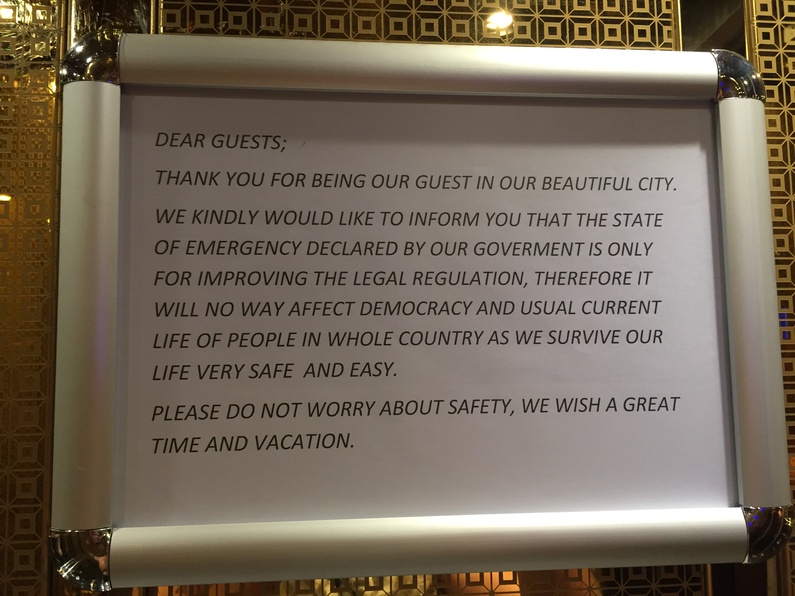

Beşiktaş is one of Turkey’s biggest football clubs, and the attack on 10 December was the equivalent of bombing Old Trafford or the Stade de France. Yet, touching down in Istanbul, it was not immediately obvious an attack had occurred. I had no problem getting through the sleepy Sabiha Gökçen Airport; the first person to discuss what had happened was the hotel receptionist who, while clearly shaken, said I should not be put off visiting the city and declared that she’d go to a football match that very evening. A notice in the hotel elevators informed me that the state of emergency, which had been in place since July’s coup, "will no way affect democracy and the usual current life [sic] of people."

The receptionist was right: Istanbul that day was gleaming in the winter sun. Everything was open, with the streets full of shoppers and the Galata Bridge lined with fishermen. The notice in the hotel lift, however, was less accurate. Armed police were posted at every bazaar; bags were checked at every museum. And, as I realized while wandering through the deserted Sultanahmet tourist district that evening, I was one of few tourists left in the city. I passed empty restaurant after empty restaurant on my way to dinner before I eventually settled on a friendly-looking place, the few patrons of which were almost all relatives of the owner.

The receptionist was right: Istanbul that day was gleaming in the winter sun. Everything was open, with the streets full of shoppers and the Galata Bridge lined with fishermen. The notice in the hotel lift, however, was less accurate. Armed police were posted at every bazaar; bags were checked at every museum. And, as I realized while wandering through the deserted Sultanahmet tourist district that evening, I was one of few tourists left in the city. I passed empty restaurant after empty restaurant on my way to dinner before I eventually settled on a friendly-looking place, the few patrons of which were almost all relatives of the owner.

According to the Turkish Ministry of Culture and Tourism, 10 million fewer tourists arrived in Turkey in the 11 months up to November 2016 then in the previous year – a drop of almost a third. They’ve been scared off by ISIS, the coup, and the TAK (the Kurdish group behind the Vodafone Arena attacks), who have warned foreigners to stay away. The empty restaurant I ate in was reflective of an economic tragedy for a country where 5% of the economy and 8% of all jobs are dependent on tourism, according to the World Tourism Council. In fact, the only country to register a significant increase in tourism to Turkey during the same period was Saudi Arabia.

Istanbul’s cosmopolitanism is enshrined in its very geography; you can get on a ferry in Europe and 10 minutes later arrive in Asia. It’s the same historically: for 916 years the Hagia Sophia was a church, then a mosque, and is now a museum. Yet 10 years of authoritarian rule under Recep Tayyip Erdogan has made Istanbul an anomaly in Turkey. As Turkey reorients towards Russia and the Middle East – with a $20 billion Turkish-Gulf investment fund announced in January – Islamists are being emboldened. Funding for the government’s Religious Affairs Directorate was quadrupled in 2015, and on the 30 December 84,000 mosques broadcasted sermons declaring New Year celebrations "illegitimate."

Ortaköy, the suburb in which the Reina nightclub was located, is a relic of that youthful, cosmopolitan and now "illegitimate" Istanbul. When I visited I saw a typical university suburb – beanie clad students, alcohol in abundance, and a TV reporter interviewing passers-by on healthy eating. What I didn’t see were the mass sackings of these students’ professors – every dean in the country was suspended after the coup – or the closure of more than 160 news outlets. Unlike sudden terrorist attacks, the erosion of Istanbul’s diverse culture isn’t immediately obvious to a foreigner on a four-day trip.

Ortaköy, the suburb in which the Reina nightclub was located, is a relic of that youthful, cosmopolitan and now "illegitimate" Istanbul. When I visited I saw a typical university suburb – beanie clad students, alcohol in abundance, and a TV reporter interviewing passers-by on healthy eating. What I didn’t see were the mass sackings of these students’ professors – every dean in the country was suspended after the coup – or the closure of more than 160 news outlets. Unlike sudden terrorist attacks, the erosion of Istanbul’s diverse culture isn’t immediately obvious to a foreigner on a four-day trip.

I have great memories of the Istanbul, from sipping spiced Turkish coffee to snow falling on the Blue Mosque. I won’t miss the corrosive and exhausting tension that Istanbul’s residents must live with year-round. The continuing war in Syria and the breakdown of the peace process with the Kurds won’t make the city any safer, and the Turkish parliament is close to giving Erdogan even greater presidential powers. I fear for places like Ortaköy, and can’t avoid the feeling that the city I saw is slipping from existence.