Time to look at customs

Published on

Translation by:

sarah parker

sarah parker

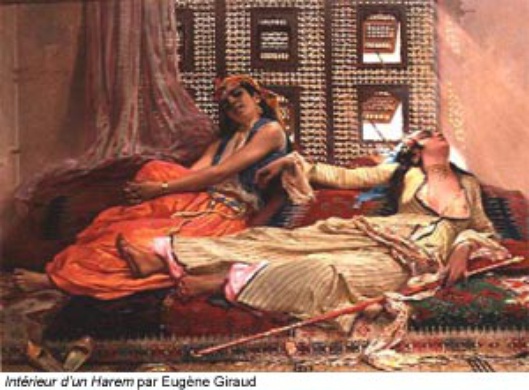

In Turkey, women have won numerous rights which have stunned the Muslim world. Despite this, Muslim traditions are often stronger than the simple right to life and respect

As regards women’s rights, even though Turkey is in many ways ahead of other Muslim countries, in reality, morals have not really changed that much. Legally, Turkish women have many rights: Women in Turkey gained the right to vote (1930) and the right to stand in elections (1934) before some European countries. The most recent laws grant women the right to begin divorce proceedings and, since 2001, they no longer have to have their husband’s permission to go to work. In January 2002, Turkish women became equal with men in legal terms.

As regards women’s rights, even though Turkey is in many ways ahead of other Muslim countries, in reality, morals have not really changed that much. Legally, Turkish women have many rights: Women in Turkey gained the right to vote (1930) and the right to stand in elections (1934) before some European countries. The most recent laws grant women the right to begin divorce proceedings and, since 2001, they no longer have to have their husband’s permission to go to work. In January 2002, Turkish women became equal with men in legal terms.

Therefore it seems that Turkish women enjoy a certain amount of freedom. But is this really the case in every day life? Studies published on the situation of Turkish women unanimously said “no”. After several decades of reform, customs and religious practices still dominate the lives of the majority of Turkish women. For example, results of a study of 1000 women from east and south-east Turkey, carried out by the Women for Women’s Human Rights (WWHR) movement, show that Turkish women do not have total freedom to choose a career and that a patriarchal system still dominates. Half of Turkey’s population lives in rural areas and women working in the agricultural sector are often not even paid. According to the 1993 census in Turkey, 32% of women were still illiterate. Moreover, even though women theoretically have the right to divorce their husbands, few do, despite suffering from verbal or physical abuse. More than half claim their husbands would kill them if they committed adultery. According to a study by Ankara University, a third of Turkish women think victims of domestic violence deserve it.

Some men simply do not wish to cooperate

Of course laws exist, but “attitudes do not change over night” according to Kirsty Hughes, from the London School of Economics’ European Faculty. “Many laws, granted because of pressure from feminist groups, are very recent and women do not know about them”, explains Sermin Utku Bilgen from the Mor Cati Foundation. He continues “The laws must be enforced and, along with this, information campaigns are crucial. Several feminist groups try to inform women about their rights. Once enlightened, they can think about things more clearly because, in the end, it is the women who will decide”.

Sermin is certain that the media has really helped women’s cause. “When the feminist movement began, towards the end of the 1980s, newspapers were writing about it all the time.” This helped women to understand that abuse can be not only physical but also verbal, psychological and economic. “They also understood that women could be raped even within a relationship. Before, it was a taboo subject. During fundraising events, there was mockery from all parts, like ‘oh, you are saving women but why not the men who are abused too?’” But it must be acknowledged that despite increased awareness, women are not always supported. “When a woman goes to the police station for example, very often the police do not really try to help them. If some are not themselves aware of the current laws, others, simply because they are men, do not really want to cooperate with the victim.”

Fortunately, a growing number of women are becoming police officers, members of parliament or quite simply employed. Feminist movements agree that the problems are gradually improving. “We must continue to inform women and find creative solutions,” Sermin does not mind repeating. “But those must be adapted for different groups in society, because the problems are different from one area to the next. A campaign to encourage young girls to go to school, which has been compulsory since 1994, is being launched in Turkey at the moment. The problem is that the message is not reaching women living in rural areas, where many are illiterate (62% of women have never been to school or they left very early), or do not speak Turkish. In some families, we see that they are not interested in sending their daughters to school because it would be too much hassle just get there” explains the feminist activist. “In other families, it is the father who refuses. It is often very difficult to counter men’s ignorance and their sense of honour.”

Translated from Du temps pour rivaliser avec les coutumes