The undertaker of the Calais Jungle

Published on

Over the last few weeks, the demolition of the Calais Jungle has been extensively covered by media outlets. What is seldom mentioned is that Europe will be confronted with the headstones of those who died in a strange land for years to come. We met Brahim Fares, the funeral director of Bab El Jenna; the only Muslim funeral parlour in close proximity to the Calais Jungle.

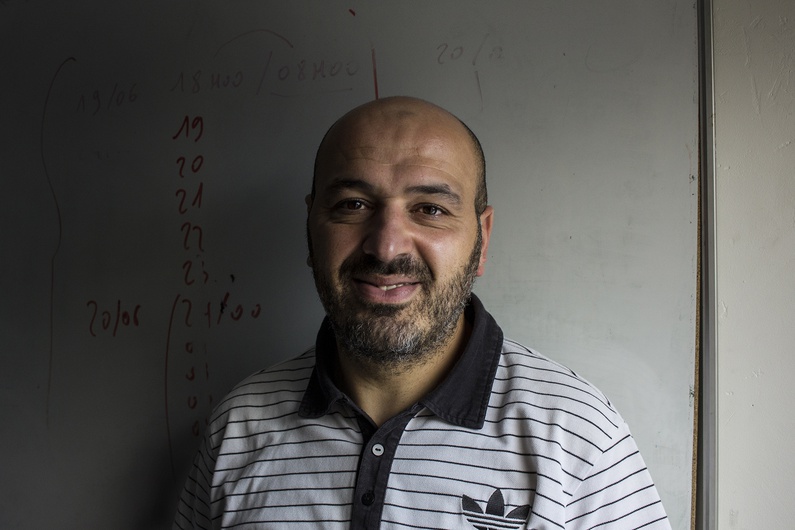

The headquarters of Bab El Jenna are essentially an extension of Brahim Fares' house. Tucked away in a small cul-de-sac in Grande-Synthe, the contrast between the modesty of the premises and the huge scale of his work is striking. Being the only funeral director within about 120km of Calais equipped to perform Muslim burials, Brahim’s duties certainly carry weight. With a warm smile and a handshake, he sat us down in his office to begin the conversation.

Brahim had already been managing a security company for 15 years when he decided to open Bab El Jenna. He was concerned with the lack of funeral parlours that accommodate Islamic burials and decided it was time to take action. "As a Muslim, it is my duty to grant my brothers and sisters a proper burial," he added with a whisper of positivity. At first, Brahim covered all the costs of the burials. This meant paying for administrative costs, the coffin, the plot, the digging of the grave, the headstone, and of course the transport. Naturally this became too much of a burden to carry, especially when he started working with refugees two years later.

"One hand cannot clap itself"

The organisations that initially took care of refugee burials - such as Oumma Fourchette, Charity Refugees France and the Secours Catholique - approached Brahim three years ago. Before that, they worked with other funeral parlours in the area, even if they were not Muslim. Taking on all the responsibilities themselves proved to be demanding: the organisations had to take care of all the paperwork, find an imam for the bathing rituals, find another person to help with the burial, and contact the mosques to accommodate the pre-burial prayers. Now that they have found Brahim, they have a shoulder to lean on.

The organisations that initially took care of refugee burials - such as Oumma Fourchette, Charity Refugees France and the Secours Catholique - approached Brahim three years ago. Before that, they worked with other funeral parlours in the area, even if they were not Muslim. Taking on all the responsibilities themselves proved to be demanding: the organisations had to take care of all the paperwork, find an imam for the bathing rituals, find another person to help with the burial, and contact the mosques to accommodate the pre-burial prayers. Now that they have found Brahim, they have a shoulder to lean on.

Without ever questioning the immense workload he was going to inherit, Brahim agreed at the drop of a hat. Just as before, he started out paying for everything. But "more and more refugees were dying, and that’s when I realised that one hand cannot clap itself; it simply became too expensive." Brahim and the organisations decided that they would work together, using their network of active donators to fund proper Muslim burials for refugees along with repatriation requests.

Despite their collaboration, Brahim still chooses to take on most administrative costs. Rather than paying the usual cost of about 2200 EUR for a traditional burial, going through Bab El Jenna means paying only 1600 EUR. The same goes for the repatriation of some refugees, rather than paying 4000 EUR, Bab El Jenna cuts it down to 3000 EUR. Repatriation requests make up about 30% of the refugee cases that Brahim has worked with. Brahim smiles, raises his shoulders almost apologetically and concludes: "You know for us, soil is soil. God is also present here in France. He is everywhere."

"A perilous journey... only to find death"

"It breaks my heart to know that [a refugee] made the perilous journey all the way to this strange land, only to find death," Brahim said. The most recent burial he has organised for a refugee was a premature newborn, whose tiny body was recovered from the Calais hospital on 12 October. Before that, Brahim buried the body of Daoud Ibrahim Adam, a 48-year-old Sudanese refugee who had suffered a long illness.

Brahim is there from the moment the death is announced until the end of the funeral, making sure he visits the graves of those who passed before, reminiscing their often short-lived existence. When Daoud passed away, Brahim was contacted by Abou Bakr from Oumma Fourchette. As it was a natural death, they could proceed straight away with organising the burial. It is paramount in Muslim tradition to bury the body as fast as possible after someone dies, Brahim explained: "No one wants to be stuck in God’s waiting room." After filling out the necessary paperwork, he bathed and shrouded the body in white cloth in a room provided for by the hospital.

Brahim is there from the moment the death is announced until the end of the funeral, making sure he visits the graves of those who passed before, reminiscing their often short-lived existence. When Daoud passed away, Brahim was contacted by Abou Bakr from Oumma Fourchette. As it was a natural death, they could proceed straight away with organising the burial. It is paramount in Muslim tradition to bury the body as fast as possible after someone dies, Brahim explained: "No one wants to be stuck in God’s waiting room." After filling out the necessary paperwork, he bathed and shrouded the body in white cloth in a room provided for by the hospital.

Brahim proceeded to explain the bathing and shrouding ritual: "We wash the bodies just as we would wash them if they were alive. Three times the hands, three times the mouth, three times the nose, three times the face... After we bathe the right side of the body, then the left. Then we embalm the body and enshroud it with white cloth, leaving the face exposed."

If a refugee dies due to an accident, which is often the case when taking high risks in crossing motorways to jump on moving lorries, the police must get involved. Then, the body is sent for an autopsy at the IML (Institut Médico-Legale Lille). Only if the body is largely disfigured does Brahim replace the traditional bathing by simply touching a stone to the body.

If a refugee dies due to an accident, which is often the case when taking high risks in crossing motorways to jump on moving lorries, the police must get involved. Then, the body is sent for an autopsy at the IML (Institut Médico-Legale Lille). Only if the body is largely disfigured does Brahim replace the traditional bathing by simply touching a stone to the body.

Brahim then made sure that the grave had been dug, the coffin paid for, and the paperwork completed in order to transport Daoud from the hospital in Dunkirk to the cemetery in Grande-Synthe. With a smaller procession, the pre-burial prayers are usually done in a mosque. However, given that Daoud befriended a large community of Sudanese in the camps and his 'foyer', the prayers had to be done at the cemetery. With no imam around, Brahim assumed the position and took charge of the prayers and invocations before everyone proceeded to cover the coffin with soil. "Everyone takes his turn in covering the body. Each grain of sand is a symbol of one’s faith, and each grain of sand is an offering to God. This is crucial." As his Sudanese family couldn’t be present at the funeral, Brahim and Oumma Fourchette worked tirelessly to photograph and film the funeral so that they could participate, even if only from a distance.

The grave will be kept at the Grande-Synthe cemetery for up to 15 years. To extend this timeframe, Brahim would have to raise more money. In Calais, keeping a grave for an extra 15 years costs 279 EUR, compared to 100 EUR for 30 years in Grande-Synthe, and 500 EUR for 30 years in Tatinghem. As the grave keepers do not maintain the graves, it is up to those close to the deceased to do so. On our last visit to Calais Nord cemetery, a refugee and activist from the Jungle were watering and decorating the graves to honour the dead.

The grave will be kept at the Grande-Synthe cemetery for up to 15 years. To extend this timeframe, Brahim would have to raise more money. In Calais, keeping a grave for an extra 15 years costs 279 EUR, compared to 100 EUR for 30 years in Grande-Synthe, and 500 EUR for 30 years in Tatinghem. As the grave keepers do not maintain the graves, it is up to those close to the deceased to do so. On our last visit to Calais Nord cemetery, a refugee and activist from the Jungle were watering and decorating the graves to honour the dead.

"The one essential thing is to retain your humanity"

"I would have wanted for things to be easier for [the refugees]," says Brahim. "I was speaking to a lady at the town hall who was complaining about the crisis. At once, I told her: 'If you heard one gunshot here you would leave immediately. If anybody heard a gunshot, they would pack up their things. The whole town would leave!' You know, the refugees are not here to have fun. The one essential thing is to retain your humanity."

Besides the emotional strain, preserving the traditions of Islamic burials in France means overcoming obstacles. For instance, it is custom to bury the body without any casket or coffin. But due to the rising water levels in the ground, the French law requires that each body be buried in a coffin. Moreover, Brahim explained that in countries where Islam is the dominant religion, funeral parlours don’t even exist. The burial process is completely free and more a rite of passage than anything.

Then there is the problem of identification. Refugees who are killed in accidents, especially those who try to jump onto moving trucks, are often unidentifiable due to their injuries. Without Brahim and the organisations in the Jungle working to provide a proper funeral, they would be cremated and, due to their dire economic condition, placed in unmarked graves. Cremation is forbidden under Islamic tradition.

Still, Brahim remains hopeful, incessantly working towards granting refugees the proper burials they deserve. He is even thinking of buying a larger office for his funeral parlour in Grande-Synthe. But the struggles persist, and he is currently working on a difficult case. A Sudanese refugee was found dead on September 24 2016 due to a motorway accident, and has yet to be buried. His body is still at the IML in Lille and, because there isn’t enough cooperation from the Sudanese consulate in Paris, he cannot be buried without proper identification (according to French law). He has been in 'God’s waiting room' since 24 September. Brahim shakes his head in disbelief. "Every week I call the police to see if there has been news, but no, nothing."

Still, Brahim remains hopeful, incessantly working towards granting refugees the proper burials they deserve. He is even thinking of buying a larger office for his funeral parlour in Grande-Synthe. But the struggles persist, and he is currently working on a difficult case. A Sudanese refugee was found dead on September 24 2016 due to a motorway accident, and has yet to be buried. His body is still at the IML in Lille and, because there isn’t enough cooperation from the Sudanese consulate in Paris, he cannot be buried without proper identification (according to French law). He has been in 'God’s waiting room' since 24 September. Brahim shakes his head in disbelief. "Every week I call the police to see if there has been news, but no, nothing."