The Tunisian bloggers: Revolution 2.0?

Published on

Translation by:

Sophia BengtssonIn 2011, the world celebrated the Tunisian revolution 2.0. If the bloggers were the heroes, the internet was their weapon of choice. Three years later, in the midst of cyber threats and the return of the traditional political parties, social media has turned out to be a double-edged sword even for those who were at the forefront of the mobilization. Long live the bloggers?

I meet Lina Ben Mhenni at the Grand Café du Theatre in Tunis. She arrives catching her breath. As she takes her seat, she signals to her body guard to give us some privacy. She has come straight from the university where she teaches. I start to speak, but she looks in the other direction, across the road, at the hundreds of people passing by, the lines of taxis along the street.

Three years ago, in 2011, this was the setting of the Tunisian cyber-revolution; a first in the history of revolutions. Even as one of the most famous bloggers in the country, Lina says it’s all a myth. “People were dying in the streets, not online”, she says- seemingly tired of incessantly explaining the same thing over and over. The barbed wire that still runs alongside the street adds some weight to her words.

A Tunisian girl

Lina was a guest on French television in 2011. Tariq Ramadan, a well-known Arabic intellectual, accused her and other bloggers of not being real spokesmen for the people, and of being paid by American organizations.

“Personally, I don’t know anybody who has received money for starting a blog. Money for what? How much does it take to start a blog?”, Lina says dryly, recalling the TV show.

Her own story isn’t far from a Tarantino movie: in 2007 she started her first blog, a Tunisian girl on a laptop “bought in a regular Carrefour”. Initially she admits it was “a blog for futile questions”. But with the censorship under Ben Alì and the nomination for the Nobel Peace Prize, suddenly Lina became one of the most important faces of the “revolution”.

Today, with one dictator gone and a new constitution, Lina lives with constant police protection. “Before the revolution I was in a kind of prison, but at least it was a bigger one. Today I suffer from massive defamation campaigns and death threats on facebook. I wouldn’t survive without police protection”, she explains, gazing at her body guard with a mix of sarcasm and resignation.

Today, with one dictator gone and a new constitution, Lina lives with constant police protection. “Before the revolution I was in a kind of prison, but at least it was a bigger one. Today I suffer from massive defamation campaigns and death threats on facebook. I wouldn’t survive without police protection”, she explains, gazing at her body guard with a mix of sarcasm and resignation.

How did this happen? Weren’t the bloggers at the forefront of it all loved by the people of the Tunisian revolution? Wasn’t the internet the weapon of choice for the young generation? “Blogs, social media, the internet… during the revolution they went from being important tools to becoming double-edged swords,” Lina admits, before delivering her judgement: “three years ago I thought that everybody wanted to improve our country, but I was an idealist.” With a temperature of barely 15 degrees, the rain is falling over Tunis. The weather, just like the picture of the fragmented cyber community that Lina is painting, clashes with the expectations of the West.

The battlefield

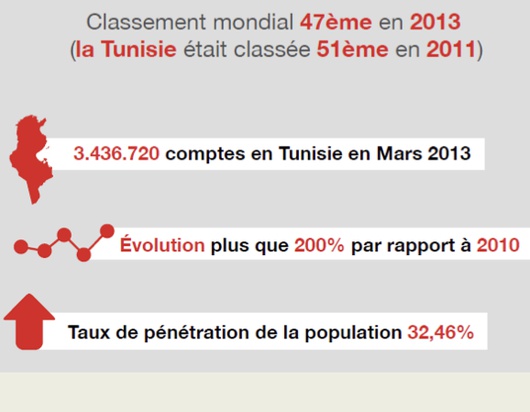

In relation to national population, Tunisia has the largest number of Facebook profiles of any country in Africa and the Arab world. In 2011, 50% of Tunisian internet-users had a Facebook account. Today, the amount of Zuckerberg-followers has reached 3,4 million and the number suggests that Tunisia has been thoroughly permeated by social media. (see infographic)

largest number of Facebook profiles of any country in Africa and the Arab world. In 2011, 50% of Tunisian internet-users had a Facebook account. Today, the amount of Zuckerberg-followers has reached 3,4 million and the number suggests that Tunisia has been thoroughly permeated by social media. (see infographic)

Perhaps this was one of the reasons that Abdel Karim, 37, founded the Social Media Club of Tunis in 2013. His objective? To make young people aware of how these platforms can be used for politics (60% of Tunisian facebook users are between 24 and 34 years old). Abdel comes from Zaghouan (50 km south of the capital), where pre-2011 involvement in politics amounted to “applauding whichever official was on duty, on behalf of Ben Alì”. Having lived in Tunis since 2002, he speaks Arabic and French, but also understands Italian: the TV antenna at his home picks up RAI 1. I meet him together with Henda, 30, who comes from the Ariana-quarter in the far north of the capital. They both call themselves bloggers and activists and are holding a lecture on web radio in the basement of the Tunisian Internet Agency (ATI). Ten people are following the lecture. The sun is shining through the windows facing the courtyard.

The shadows of the palm trees grow long on the other side of the window. Abdelkarim takes out his sticker covered laptop and puts it on the table. The restraurant is practically deserted.

The shadows of the palm trees grow long on the other side of the window. Abdelkarim takes out his sticker covered laptop and puts it on the table. The restraurant is practically deserted.

“The bloggers? They are free radicals, every man for himself”, he says, “but the Ennahda party is now recruiting young people to monitor social media and to conduct political campaigning online: it’s become a battlefield”.

It seems that social networks, spearheaded by Facebook, represent the new Wild West of politics, where Islamists, communists and anarchists fight it out. I ask about the role of bloggers during the revolution and Henda tells me straight out that “the bloggers had a limited role in the course of the upheaval”- she rarely uses the word revolution. According to her “there was a general tendency in the media to try and downplay the role of other active social movements in Tunisia; organized groups that were not always peaceful and were not satisfied with what was achieved.”

So, what was the role of the bloggers?

“Every revolution needs a face” Henda confesses cynically. As I ask Abdelkarim about the allegations made by Tariq Ramadan, a car passes the window with a police escort and his gaze follows it as he smiles ambiguously. When he answers me, his smile is gone.

“Five famous Tunisian bloggers were trained by an American Think Tank”- he pauses before continuing- “after all, who could have refused? To get rid of Ben Alì we had to make a deal with the devil!”

It’s hard to disagree with him. Ten years ago, long before “blogger” acquired a political connotation, “the regime trained people to supervise the internet and participate in forums”, Henda explains. At that time, the internet was used almost exclusively for private matters. Then, everything changed, with the arrival of a “political web”, the revolution 2.0 and a new government. And yet, talking to these activists you wonder if things really did change. In a way it is as though Ben Alì and the Tunisian revolution are both “dead”. And it seems that even the bloggers aren't doing so well.

This article is part of the Euromed Reporter project, conducted in partnership with I WATCH and Search For Commong Ground and supported by the Foundation Anna Lindh.

Translated from I blogger di Tunisi: "Non chiamatela rivoluzione 2.0"