The times are a chang(el)ing

Published on

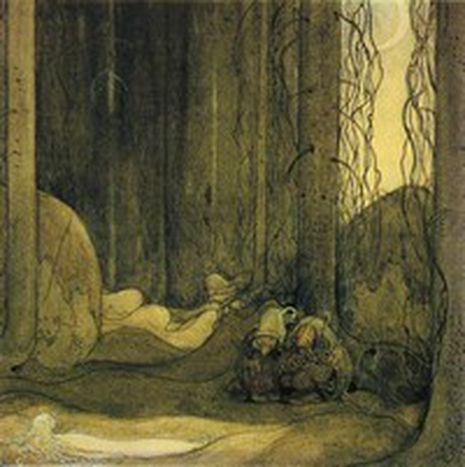

For centuries, stories of changelings have circulated in Europe. What could explain the similarity of these tales of human babies being snatched, and being replaced by changelings – elven babies with unquenchable appetites?

Once upon a time, in what was then the town of Breslau, there lived a nobleman. Every summer he had a crop of hay that he forced his subjects to harvest. One year, there was a young mother among the workers who had barely recovered from giving birth. While she went to help with the haymaking, she left her child alone in the grass. After working for a while, she returned to nurse him. She stared, and screamed in horror. The child sucked milk so greedily and screamed in such an inhuman fashion that she knew it could not be her child. At length, she went to the nobleman to ask his advice. He told her "Woman if this is not your child, take it out to the meadow where you left your previous child and beat it hard with a switch." When she did so, the child screamed loudly, and, at that, the Devil came, bringing back her stolen child.

Tall tales

This story was recorded by the Brothers Grimm, but variations on it appear around Europe. While many of the details change, the structure always remains the same. The story starts when a young mother is called away to work. As she is working, fairies come and switch her baby with an elven child. This new child displays a fiendish hunger. In a Norwegian version of the story, the changeling “ate so much that the people at Lindheim have been living from hand to mouth, generation after generation, on his account."

The mother, exhausted, seeks help from someone in the community. In three of the Grimms' tales, the advice comes from ordinary people, but often the advice comes from feudal lords or priests. However, the advice is always the same - reveal the child for the impostor that it is: either by hurting it or making it laugh.

The 16th Century German religious reformer Martin Luther suggested the former route. In his writing he argued that a changeling was a child of the devil without a human soul. Luther had few reservations about putting such children to death. A more humane method to reveal the elf is given by a story from Scotland, in which a neighbour instructs the mother to boil water in eggshells. When she does this strange request, the baby bursts out laughing, and is revealed as an impostor. The elves then come and retrieve the child – though it is only in the later sanitised versions of the story that the original baby is returned…

Taller tales

What could explain how this story has travelled all over Europe? The explanation lies in what we think folklore is supposed to be about. Some claim that folklore is a proto-science, a means of explaining events that fall outside our control, but for which we have no satisfying rationale. In such a reading, the myth of the changeling would explain disabled children. How could two healthy adults produce a disabled child? Simple – it was the elves that stole the baby.

If one was to believe such a functionalist explanation, then the legend of the changeling could also justify what one does with such a baby. In all the stories the mother seeks the consul of the community, who suggest that she beats the child, or in several English varieties of the story, put it into boiling water. Such an explanation would mean that the story of the changeling justifies the infanticide that could be the unfortunate consequence of the increased demands made on a family by a disabled child.

But such an explanation doesn’t really convince –it doesn’t explain any of the details of the story (why try to make the baby laugh), nor does it explain why the babies are always snatched by the elves whilst the mothers are working.

Watching the baby, looking out for the mother

Another explanation suggests that these cautionary tales of babies snatched just after birth help to justify shielding mothers from heavy work immediately after childbirth. In the Grimms' tale "The Changeling in the Thuringian Forest," the exchange of infants occurs when the mother leaves her baby alone in the house while she fetches wood. At the end of the tale, once the changeling has been drive away, the nobleman who dispatched the woman to gather wood resolves to never again force a woman who had recently given birth to work. The fear of changelings led to babies needing to be constantly watched. In the early twentieth century Greeks refused to leave their children during their first eight days, for a fear of witchcraft, while in the nineteenth century Germans placed a right shirt sleeve, a left stocking and black cumin in the cradle as protection.

Watching out

These arguments are ultimately unsatisfying because they assume that these stories play only a functional role in society. In such explanations, the advent of science and the end of agricultural society would also bring about the end of such stories.

A glance at the magazines of today tells you otherwise. There are stories of alien abducting children and of babies being mixed up in crowded hospital nurseries. Like the stories we have heard, these modern day changelings speak of a common horror – producing something from yourself that you do not recognise. Changelings are still amongst us, and the universality of the concerns to which the stories speak suggests that they will be around for some time to come.