The Story of Coffee

Published on

Since seeing cafes full with people drinking coffee in the middle of the workday I arrived in Bulgaria, I keep suspecting that Bulgarian economy and society are very much kafence-driven. Not only here, though, coffee isn’t just a beverage or commodity. Coffee has influenced societies throughout history, and the impact on Muslims and Christians is revealingly similar.

Coffee (just like Christianity) came to change Europe from the East. From Arabic comes the word qahwah that entered Turkish as kahve, which then gave birth to the European words for coffee: kawa in Polish, koffie in Dutch and kave in Hungarian.

The coffee tree originated in Africa, around present-day Ethiopia. As other contemporary Africans, Ethiopians probably boosted their energy with balls of coffee and animal fat and took time out with wine from coffee-berry pulp. Then, the plant was domesticated and taken to Yemen and until the end of the 17th century Yemen provided almost all the world coffee supply.

Coffee penetrated the Ottoman Empire from conquered Egypt and Hejaz (region of Saudi Arabia) in the early 16th century. The drink, brought by the merchants trading with the Ottomans, officially entered Europe through Venice in 1615. From Venice, then European trading headquarters, coffee and coffeehouses spread to the rest of Italy. London merchant Edwards brought coffee to England in 1652, again from the Ottoman Empire, and in a few years the city consumed more coffee than any other. The Austrians, according to a legend, discovered coffee with the help of interpreter Georg Franz Kolschitzky who taught them how to use several tons of green coffee left by Ottomans nearby Vienna after the 1683 siege. Soon the Viennese actively engaged in drinking coffee and commemorated Kolschitzky with a memorial.

Coffee penetrated the Ottoman Empire from conquered Egypt and Hejaz (region of Saudi Arabia) in the early 16th century. The drink, brought by the merchants trading with the Ottomans, officially entered Europe through Venice in 1615. From Venice, then European trading headquarters, coffee and coffeehouses spread to the rest of Italy. London merchant Edwards brought coffee to England in 1652, again from the Ottoman Empire, and in a few years the city consumed more coffee than any other. The Austrians, according to a legend, discovered coffee with the help of interpreter Georg Franz Kolschitzky who taught them how to use several tons of green coffee left by Ottomans nearby Vienna after the 1683 siege. Soon the Viennese actively engaged in drinking coffee and commemorated Kolschitzky with a memorial.

Among both Muslims and Christians, coffee was seen as an alternative to alcohol. Muslim societies, prohibited from intoxicants by a number of Qur’ānic verses, appreciated the invigorating effect of coffee beans. Arab warriors believed that aromatic breads from dried and toasted coffee beans, with butter and salt, would help them fight better. In Yemen, the state officials at first promoted drinking coffee or chewing coffee beans as an alternative to chewing stimulating and addictive khat plant, still used, but illegal, today. In Europe, while the new drink was widely seen as a substitute for spirits, drinks stronger than coffee were also consumed in coffeehouses.

Among both Muslims and Christians, coffee was seen as an alternative to alcohol. Muslim societies, prohibited from intoxicants by a number of Qur’ānic verses, appreciated the invigorating effect of coffee beans. Arab warriors believed that aromatic breads from dried and toasted coffee beans, with butter and salt, would help them fight better. In Yemen, the state officials at first promoted drinking coffee or chewing coffee beans as an alternative to chewing stimulating and addictive khat plant, still used, but illegal, today. In Europe, while the new drink was widely seen as a substitute for spirits, drinks stronger than coffee were also consumed in coffeehouses.

As for coffee’s health effects, if was seen interchangeably as a powerful medicine and a harmful substance. At the beginning of the second millennium C.E., Avicenna proclaimed coffee a medicine. Yet once “half the Cairo Medical Association stood up on its hind legs and told the grand vizier that coffee was responsible for all diseases from athlete's foot to zymosis.” In Europe, coffee was often sold next to lemonade by vendors and believed to have a positive health effect. Still, in Germany doctors warned women against coffee as dangerous for bearing children. Clergymen also attacked it, as the drink of infidels. They accepted coffee only when, the legend goes, Pope Clement VIII tried it and became fond of the drink, thus “baptizing” it.

As for coffee’s health effects, if was seen interchangeably as a powerful medicine and a harmful substance. At the beginning of the second millennium C.E., Avicenna proclaimed coffee a medicine. Yet once “half the Cairo Medical Association stood up on its hind legs and told the grand vizier that coffee was responsible for all diseases from athlete's foot to zymosis.” In Europe, coffee was often sold next to lemonade by vendors and believed to have a positive health effect. Still, in Germany doctors warned women against coffee as dangerous for bearing children. Clergymen also attacked it, as the drink of infidels. They accepted coffee only when, the legend goes, Pope Clement VIII tried it and became fond of the drink, thus “baptizing” it.

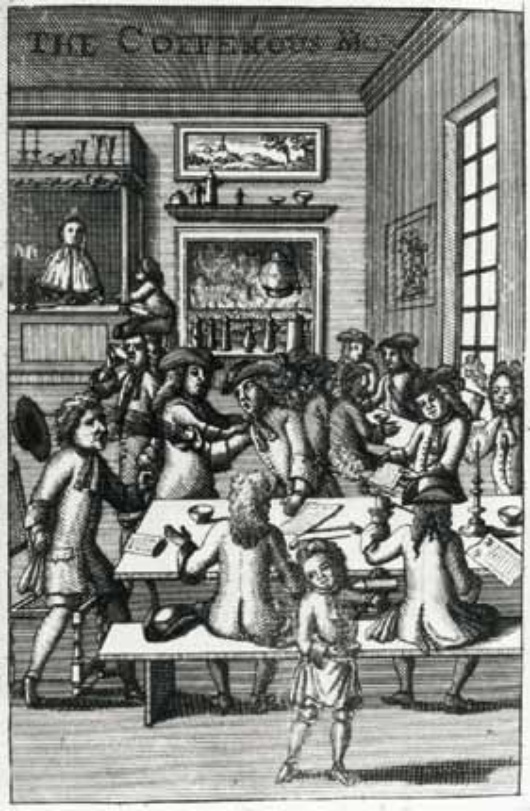

For both Christians and Muslims, a coffeehouse was really the first place of its sort: socialization, business and entertainment altogether for the price of a coffee cup. Lloyd’s, world leading insurance market, started as a London coffeehouse. In fact, most of the old London clubs are descendants of coffeehouses because different layers of the society had their own coffee drinking places. While European coffeehouses were purely secular institutions, Iranian coffeehouses could host sermons and narrations of mullahs or dervishes—but it was acceptable to ignore to them.

Coffeehouses quickly became hubs of political activity. A common question to ask on entering an old English coffeehouse was “Which is the treason table?” Charles II, king of England, eventually banned coffeehouses, but the widespread opposition made him reopen them in a week. Sultan Selim II, Ottoman emperor, prohibited coffee shortly after it was introduced in his land. In both cases the prohibition campaigns on coffee or coffeehouses were brief and “tended to peter out as the initial moral ardor waned or was deflected by bribery,” or simply called off once the tax revenues fell too much.

Coffeehouses quickly became hubs of political activity. A common question to ask on entering an old English coffeehouse was “Which is the treason table?” Charles II, king of England, eventually banned coffeehouses, but the widespread opposition made him reopen them in a week. Sultan Selim II, Ottoman emperor, prohibited coffee shortly after it was introduced in his land. In both cases the prohibition campaigns on coffee or coffeehouses were brief and “tended to peter out as the initial moral ardor waned or was deflected by bribery,” or simply called off once the tax revenues fell too much.

Coffee largely shaped the modern perception of the night as a time not only for rest, but also for activity. The prolific French writer Voltaire is said to have enjoyed 50 coffee cups a day. Only later, in the 1800s, enormous Brazilian harvests of energizing beans turned coffee from an exquisite beverage to an everyday drink.

The history of coffee and coffeehouses has also been a tale of global trade and international relations. For instance, coffee popularity dramatically shrank in England when tea successfully took on the lands of English-dominated Sri Lanka (Ceylon before 1972). Today at least for 25 million farming families in 50 countries the evergreen plant is the major source of income. In 1963, International Coffee Organization was established under the auspices of the United Nations in order to regulate the voluminous coffee market. Still, global deregulation, technological innovations and market tendencies bring instability to the small producers of coffee. That’s why Europeans, as important consumers of coffee, should make sure they get their coffee in the way that’s not harmful for economies, ecologies or societies of the countries-suppliers. And, meanwhile, give a thought to how the drink has shaped their cultures and lives.

Pictures: Ottoman coffee house from Yerasimos, Stephanie, Turkish Style (New York: Vendome Press, n.d.) / The CoffeeHous Mob Ned Ward, The CoffeeHous Mob, frontispiece to Part IV of Vulgus Britannicus, or the British Hudibras (London, 1710), the British Library.