The 'state of cinema' as declared in a bay by Loch Ness

Published on

Translation by:

Hayley Worsley-Carter‘A pilgrimage’ was the name chosen by actress Tilda Swinton and documentary maker Mark Cousins for their new festival, a unique travelling celebration of cinema. In August, masterpieces of the seventh art were shown across Scotland. Memories of a week spent somewhere between poetry and politics, dream and reality

‘Do you remember that film, Cinema Paradiso?’ Standing with my feet on the sand, facing the North Sea that lines the small seaside resort town of Nairn, north of Aberdeen, I listen to Janet speaking. It’s late and there is a fire burning on the beach. We are drinking cheap port, bought from the reduced rack of a nearby cornershop. The bottle will soon be empty. Our pilgrimage across Scotland, from east to west, from Glencoe to Nairn, has reached its sixth day and will also soon be finished, just like the Port. ‘Do you remember that film, Cinema Paradiso? That moment, when in the cinema, the audience shout, stand, applaud, electrified by what they are seeing on the screen? Well I feel like that is exactly what we have experienced this past week.’

‘Do you remember that film, Cinema Paradiso?’ Standing with my feet on the sand, facing the North Sea that lines the small seaside resort town of Nairn, north of Aberdeen, I listen to Janet speaking. It’s late and there is a fire burning on the beach. We are drinking cheap port, bought from the reduced rack of a nearby cornershop. The bottle will soon be empty. Our pilgrimage across Scotland, from east to west, from Glencoe to Nairn, has reached its sixth day and will also soon be finished, just like the Port. ‘Do you remember that film, Cinema Paradiso? That moment, when in the cinema, the audience shout, stand, applaud, electrified by what they are seeing on the screen? Well I feel like that is exactly what we have experienced this past week.’

A truck called Toutankhamion

I do remember Cinema Paradiso. I also vividly remember, with my toes in the sand, the incredible cinematographic pilgrimage in which I have participated, alongside actress Tilda Swinton and documentary film-maker and cinema critic Mark Cousins. They were two cinephiles mad enough to imagine a travelling film festival, built around a big blue lorry and around forty permanent audience-members from all corners of the globe; Brits, Germans, Canadians, Belgian, French; students, school kids, future police officers, teachers, social workers, producers, cinematographers. All were brought together in this monster on wheels, arriving in tiny villages on a bay by Loch Ness, in the shelter of an immense Glen or in the heart of the Highlands.

I do remember Cinema Paradiso. I also vividly remember, with my toes in the sand, the incredible cinematographic pilgrimage in which I have participated, alongside actress Tilda Swinton and documentary film-maker and cinema critic Mark Cousins. They were two cinephiles mad enough to imagine a travelling film festival, built around a big blue lorry and around forty permanent audience-members from all corners of the globe; Brits, Germans, Canadians, Belgian, French; students, school kids, future police officers, teachers, social workers, producers, cinematographers. All were brought together in this monster on wheels, arriving in tiny villages on a bay by Loch Ness, in the shelter of an immense Glen or in the heart of the Highlands.

For Janet, the others and me, cinema will always be as great as this huge, blue lorry. Each afternoon, the lorry, named Toutankhamion (a play on words concerning the Egyptian pharaoh and the French word ‘camion’, meaning ‘lorry’), unfurls itself in a school car park or by the banks of a lake, in Strontian, Fort Augustus or Dores. A whole other world unfolds before your very eyes. The huge back doors of the Toutankhamion part and soon reveal a cinema complete with screen, projection booth and eighty seats. This ‘screen machine’ was our world for a week, travelling the roads of rural Scotland, surrounded by striking and dramatic countryside.

To each their After Eights

'Film is one of the most accessible art forms. Even its most obscure productions can be understood by an intelligent non-specialist.'

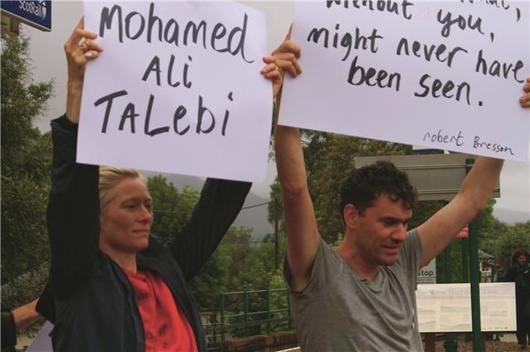

It is with a banner declaring the ‘State of Cinema’, brandished about their shoulders or fixed to two brooms with ragged fibres that, each day and at three daily screenings, Swinton and Cousins welcomed the audience, newcomers and converts, locals and passing tourists, to their pilgrimage in the big blue lorry. Theirs is a show of pure and hard activism incorporated into an unchanging and celebrated irreverence, demonstrated before each screening; a dance around incredulous spectators, a hymn (different each time, from Elvis Presley to Patti Smith right through to Marilyn Manson and on to Personal Jesus by Depeche Mode) and the declaration of the independence of the ‘State of Cinema’. Other things not on the programme but worth mentioning are the barks of Tippy the dog, the After Eight mints handed out by Tilda Swinton before the 9pm showing (at 6pm, it was cakes), Mark Cousins’ black kilt, Kenneth’s whisky and the inspired dance routines with, as an indispensable accessory, not a gilded flag but placards on which were written the names Kurozawa, Cyd Charisse, Jacques Tati, Vicente Minelli, Malcolm MacLaren or Matt Hulse.

Kurozawa, Tati, Bresson

‘Do you remember when we all shouted like crazy people whilst watching The Night of the Hunter?’ My back resting on a dune, I think of Robert Mitchum being shot at by Lilian Gish in the 1955 film and laugh. I remember Cold Fever (1955) and the Japanese man in the film crossing Iceland to pay his last respects to his parents killed in a car accident. I remember Matt Hulse’s ukulele in Follow the Master (1953). I remember Robert Bresson’s magnificent Au Hasard, Balthazar (1966) and the letter sent by his widow to thank Tilda and Mark for rediscovering her husband’s work. I remember James Cagney’s legs in Footlight Parade (1933) and I remember Monsieur Hulot (1953) by Jacques Tati. I remember the wizard’s eyes in The Throne of Blood (1957) by Akira Kurozawa and Tilda Swinton’s tears as the last, puzzling reel of A Canterbury Tale (1944) appeared onscreen. I remember all these films, be them Icelandic, British, Indian or Japanese, providing us with windows over the world.

‘Do you remember when we all shouted like crazy people whilst watching The Night of the Hunter?’ My back resting on a dune, I think of Robert Mitchum being shot at by Lilian Gish in the 1955 film and laugh. I remember Cold Fever (1955) and the Japanese man in the film crossing Iceland to pay his last respects to his parents killed in a car accident. I remember Matt Hulse’s ukulele in Follow the Master (1953). I remember Robert Bresson’s magnificent Au Hasard, Balthazar (1966) and the letter sent by his widow to thank Tilda and Mark for rediscovering her husband’s work. I remember James Cagney’s legs in Footlight Parade (1933) and I remember Monsieur Hulot (1953) by Jacques Tati. I remember the wizard’s eyes in The Throne of Blood (1957) by Akira Kurozawa and Tilda Swinton’s tears as the last, puzzling reel of A Canterbury Tale (1944) appeared onscreen. I remember all these films, be them Icelandic, British, Indian or Japanese, providing us with windows over the world.

I open Mark Cousin’s book, The Story of Film, which I found in a little bookshop in Nairn. ‘Film is one of the most accessible art forms, so even its most obscure productions can be understood by an intelligent non-specialist.’ On the beach, the fire is slowly burning out. There is no more than a drop of Port left in the bottle. Should Janet, the others and me, pop a message inside and send it out to sea? We write simply on a piece of paper: ‘We are the citizens of the State of Cinema. Here are our memories. Join us and make new ones.’

Mark Cousins, The story of film, 2004. Ed. Pavilion.

Translated from « L’Etat du cinéma » déclaré dans une baie du Loch Ness