The revolutionary pencils of Khalid Albaih

Published on

Translation by:

Maria-Christina DoulamiBorn in 1980, Khalid Albaih is widely regarded as the pencil of the Arab Spring. Not particularly happy to be labelled that way, he told us about his fight for a better future, without sparing some criticism regarding Charlie Hebdo.

For months, he attempted to publish his cartoons on various publications. Nothing. Then came the Arab Spring and those who were then talented with a pen, now became painters ready to redecorate the walls of cities, from Cairo's Tahrir Square to Beirut. He is Khalid Albaih, a cartoonist with a special background: of Sudanese origin and born in Romania, he grew up in Belgium and then moved to Doha, Qatar.

One day, the editor of a newspaper explicitly told him, "this is not our style." And he was literally thrown out of the office. It was at that time that Khalid began publishing his work online. His oeuvre can be found on the Facebook page Khartoon!, a play on words between the capital of Sudan, Khartoum, and the English term cartoon.

"True luck? Being online"

And then? Then he became the voice, or rather the pencil, of the Arab Spring. “Well, it is not exactly like that – he says – we were many. It was the newspapers who bestowed this nickname. In fact we were in hundreds, drawing during the revolutions. And many have done an outstanding job. I, simply, have been lucky because the attention was focused mainly on me.” It was a coincidence, repeats Khalid, “even before the Arab Spring began, we were all online.” And it is in this way, he continues, that they started collaborating. All (or almost) together.

And then? Then he became the voice, or rather the pencil, of the Arab Spring. “Well, it is not exactly like that – he says – we were many. It was the newspapers who bestowed this nickname. In fact we were in hundreds, drawing during the revolutions. And many have done an outstanding job. I, simply, have been lucky because the attention was focused mainly on me.” It was a coincidence, repeats Khalid, “even before the Arab Spring began, we were all online.” And it is in this way, he continues, that they started collaborating. All (or almost) together.

The objective? The change that Khalid, armed with his pencil, has already struggled for some time. It's almost a natural course for someone like him, who grew up on bread, art but, above all, politics, which is "the reason for which I was never allowed to have my own real house," continues Khalid, the son of a former Sudanese ambassador to Romania, and raised during a mission at the behest of the military government in 1989.

"When I was studying in Doha, in my class there were boys of ten / fifteen different nationalities. All there for various reasons: not by their choice and, in some cases, due to the difficult political situation of their country. And so we grew up together, curious to learn the languages and cultures of others. This is one thing that has taught me to question my point of view and to not believe that my choices are necessarily the best. "

Inspiring Khalid, especially from an artistic point of view, was Naji al-Ali, one of the world's best known Palestinian cartoonists, killed in London in 1987 by a murderer who remains unknown. “One thing that demonstrates, once again, is how powerful cartoons can be. I grew up reading those comics, fascinated by how deep, dark, interesting they were. Able to make you understand how the Palestinian situation was (and is) painful.”

Inspiring Khalid, especially from an artistic point of view, was Naji al-Ali, one of the world's best known Palestinian cartoonists, killed in London in 1987 by a murderer who remains unknown. “One thing that demonstrates, once again, is how powerful cartoons can be. I grew up reading those comics, fascinated by how deep, dark, interesting they were. Able to make you understand how the Palestinian situation was (and is) painful.”

And then came 7 January. Came the blood, came the victims and the Kalashnikovs exploding in the editorial offices of the French weekly Charlie Hebdo. In that moment, everyone turned to Khalid. And he found himself responding, having to enlighten about a newspaper, that in all honest he did not know so well. "We are not used to witnessing these kinds of things, this vulgarity - he explains – Our TVs are victims of censorship as are our books. Simply, I repeat, we are not used to this. In my work, you will never find something of this sort. And even when I try to go beyond this, I do it very carefully because the people are not used to it.” Yes, he says, he knew Charlie Hebdo but he never managed to read it because he did not share its editorial line.

"Charlie Hebdo? I never understood it"

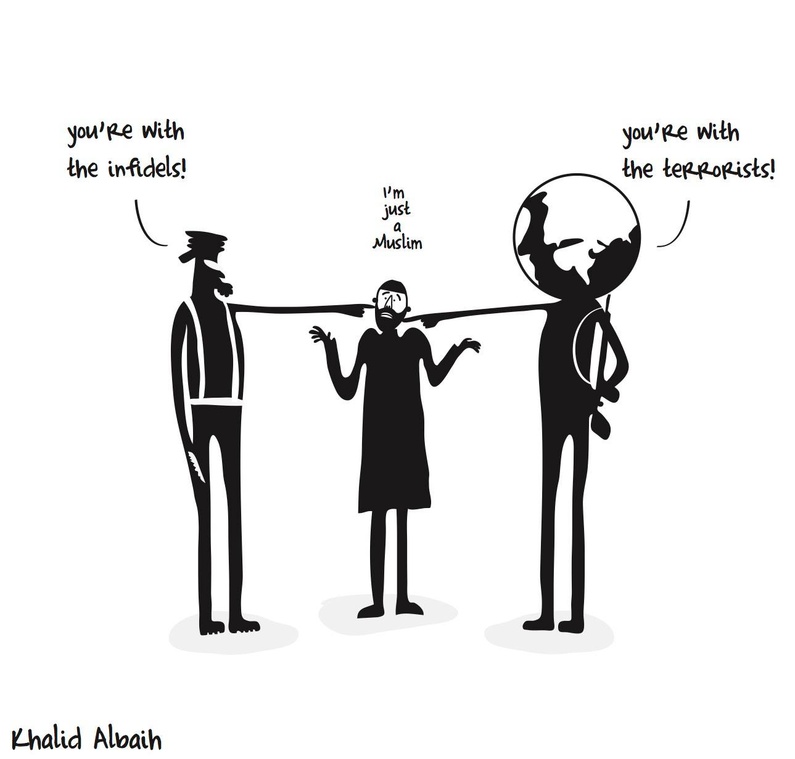

Yet, continues Khalid, on the situation of Charlie Hebdo he has no doubt: "I do not know about you – he tells me – but I still do not understand what the purpose of these people was. Of course I am against violence and I think that no one deserves to be killed, especially if they're doing their job.” The real problem, according to Khalid, is not the representation of the prophet Muhammad. “They were not the first and certainly will not be the last either. It is simply that their cartoons, for us Muslims, were and remain offensive. I think we are very 'selfish', as cartoonists we say 'this is my opinion and I do not care what you think'.” Especially in a country like France, continues Khalid, where about six million Muslims live.

Yet, continues Khalid, on the situation of Charlie Hebdo he has no doubt: "I do not know about you – he tells me – but I still do not understand what the purpose of these people was. Of course I am against violence and I think that no one deserves to be killed, especially if they're doing their job.” The real problem, according to Khalid, is not the representation of the prophet Muhammad. “They were not the first and certainly will not be the last either. It is simply that their cartoons, for us Muslims, were and remain offensive. I think we are very 'selfish', as cartoonists we say 'this is my opinion and I do not care what you think'.” Especially in a country like France, continues Khalid, where about six million Muslims live.

And with the 14 January cover, he continues, Charlie Hebdo cartoonists have done nothing other than to prove that which he once again calls "selfishness". “They could have done wonderful things. They really could embarrass those who believe in violence and terrorism. I'll tell you more, they could even call an Arab cartoonist to illustrate their front page. To speak of unity, perhaps. But they limit themselves in doing the same thing. What did they want to do? Demonstrate the ability to do anything in the name of freedom of expression? Well, no problem. For me, this is called 'selfishness'. "

Translated from Le matite rivoluzionarie di Khalid Albaih