The people want their money back

Published on

Criticism of the British rebate from EU coffers is growing, but Euroscepticism in the aftermath of the No to the constitution is manifesting itself increasingly in national greed across the continent.

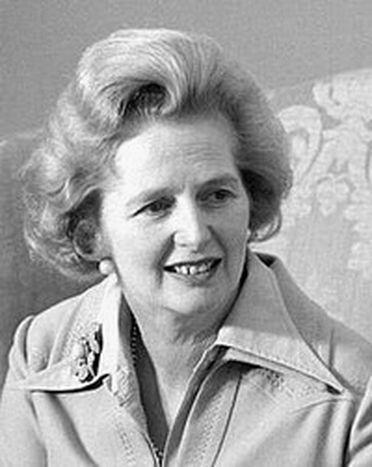

“I want my money back.” With those legendary words, spoken at the EU summit of 1984 in Fontainebleau, Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher put British Euroscepticism into words more aptly than anyone else before. According to the Iron Lady, the UK was getting proportionally less out of the European Budget than it paid in and she wanted compensation.

Valid reasons

At the time, Britain was one of the poorer states of the then European Community (EC), with a GNP per capita 10% lower than the Community average. Moreover, as one of the biggest importers of agricultural products from non-EC countries, the UK incurred massive customs duties which, in turn, helped finance the Common Agricultural Policy (CAP). Since the CAP subsidises European agriculture, the fact that Britain was paying heavily (both directly and indirectly) into a fund from which it received the least led to a sense of injustice, which Thatcher capitalised on.

For Thatcher, the logical solution was that the CAP should be overhauled and that Britain should get something in return. This calculating approach didn’t go down too well with the other member states, for whom the CAP, as the only subject on which the EC had successfully agreed a common policy, was a symbol of what the EC had achieved. But in order to stop talks from disintegrating Britain was granted its rebate, which still stands today.

Time to move on

Against the backdrop of the debate over the next budget, which attempts to limit spending in each of the EU policy areas, France and other nations have taken a firm stance against the British rebate…again. Britain is equally stubborn in its desire to hold on to its special arrangement, which currently saves it over £3 billion a year, and had even threatened to veto the whole budget if it is not kept in place. As in Thatcher’s time, Britain is still not getting as much back from the CAP as it puts in and so Blair is unwilling to budge on what is not only an economic but a politically important tool.

However, the context in which the rebate was originally agreed on has significantly changed over the years in Britain’s favour. The Brits are much better off than they were 20 years ago: since 1984 fifteen more countries have joined the EU of which many are poorer than the UK, which currently has the highest income in the EU and is ranked third in purchasing power. The British argument therefore seems less reasonable, leading the EU Commission President Jose Manuel Barroso to join in with calls for the rebate to come to an end.

Nationalist resurgence

But it is not only the UK which is trying to defend its interests and avoid paying up. As evident during the summit of European leaders on June 16-17, it seems that the public’s opposition to the proposed constitution has made political leaders strong defenders of national interests in an attempt to win confidence. French President Chirac, for example, shot down Blair’s proposal to give up the rebate in return for a reform of the CAP, knowing such reform could anger French farmers who greatly benefit from this policy. Likewise, the Dutch, many of whom (according to Motivation) voted Nee to the constitution on the basis that the Netherlands’ contribution was too high, pushed for a reduction in their EU payments.

So the constitution has stirred up a debate on the future of the EU, but in quite a different way to expected. For now, disagreement centres on the conflicting interests of the different economies within the EU; between countries with a vast agricultural sector and those that are based on trade. As always, money seems to be the subject that draws people’s attention and they want it back.