The lowdown: five queer artists in Europe

Published on

Being a queer artist is easy. Having an impact is harder; making a community more accessible to others. From Hungary, where an amendment to the constitution explicitly limited marriage as only possibly being between a man and a woman in March, to Bosnia and Herzegovina, queer artists are changing mentalities. Kati, Mel, Tonci, Andrea and Dorothee explain their stories

Mel, Bosnia

'In Bosnia, the term ‘queer art’ is always misunderstood,' says Melisa Ljubovich, 23. 'It is not specified in the artistic scene, and desperately needs to become more commonly used. Queer art isn’t that free in Bosnia, it’s progressing. The LGBT community knows the meaning of the term, but they stick closely to ‘art’ and don’t question the issue. I come from a family with an artistic tradition. I’ve always been involved in art projects, movements and colonies. I never specified my art as queer before reading about the theory and culture. Eventually the people I get to know who call themselves queer artists are no longer that queer. They start to act like old academic shitty people.'

'In Bosnia, the term ‘queer art’ is always misunderstood,' says Melisa Ljubovich, 23. 'It is not specified in the artistic scene, and desperately needs to become more commonly used. Queer art isn’t that free in Bosnia, it’s progressing. The LGBT community knows the meaning of the term, but they stick closely to ‘art’ and don’t question the issue. I come from a family with an artistic tradition. I’ve always been involved in art projects, movements and colonies. I never specified my art as queer before reading about the theory and culture. Eventually the people I get to know who call themselves queer artists are no longer that queer. They start to act like old academic shitty people.'

Mel lives her queer life to the full capacity, and is teaching young people to be queer artists, even travelling to Vienna to do so. 'Croatia and Serbia are quite advanced at promoting queer art and events, but Macedonia has more transparent queer artists.'

Andrea, Italy

Andrea, Italy

Defining Andrea Giuliano as an artist is presumptuous; he says he feels the urge to express himself in different ways: a picture rather than a statement, a performance as opposed to a party. 'As for ‘queer’, I just had a lot of poison inside me,' says the 32-year-old, who lives in Budapest. 'I was too tired of keeping it in, so I spit it out. I have always had a fascination for points of views – what’s ‘normal’ for me might be out of this world for someone else.'

Andrea is working on a homoerotic trilogy, but most of his pictures don’t deal with the queer/ gay element/ factor - whatever it is. An artist can be a queer one even without having a clue about it, says Andrea. He is also part of some activities of KLIT, a queer feminist space, sex shop and library project in Budapest. “The LGBTQIA community is just one of the many parts of society being victimised by an absurd ‘modern’ witch-hunt” he says. “A reaction against all the discrimination and violence is inevitable and badly needed. Queer art is a way to bewitch, entertain and inform”

Tonci, Croatia

'I never attended art school,' says Tonci Kranjčević Batalić. 'I find the language of arts an easy form to talk about issues. Art allows total freedom in approaching a subject, it doesn't have to be politically correct. Compared to the science or legal system, I would even say it's queer in itself.' As a lad, Tonci was terrified when he perceived that romance in TV films would end up in marriage. This was presented as the only option in life for everyone, and he was relieved when he came out.

'I never attended art school,' says Tonci Kranjčević Batalić. 'I find the language of arts an easy form to talk about issues. Art allows total freedom in approaching a subject, it doesn't have to be politically correct. Compared to the science or legal system, I would even say it's queer in itself.' As a lad, Tonci was terrified when he perceived that romance in TV films would end up in marriage. This was presented as the only option in life for everyone, and he was relieved when he came out.

'Being a ‘queer artist’ is about being critical,' he says. 'An artist can be queer without knowing it. It's not necessary to insist on the label. I aim to highlight the practices of everyday life of the gay community, and to question the dominant system from this position. I would call it ‘learning from faggotry’, as it offers a model for a different society based on common values, negotiated between individuals who make that society.'

Dorothee, Germany

In Germany queer art projects are plentiful but not in the mainstream, says Dorothee Zombronner, who has been promoting the genre in her country since she was a 22-year-old fine arts student. 'The first pictures of my ‘strange girls’ series illustrated the gap between the unaccomplished expectations of young men and women equivocated by advertising. I didn’t dare to call my art ‘queer’, even though I was working with these topics long before. I met an artist who called herself a queer artist because she loves women. Does the title depend on the art you make or on your sexuality? I'm a feminist; am I queer? Is my work feminist art because I am a woman? When I perform or tell people about my work in Germany, I get asked ‘You are so crazy! Why?’, or, as a friend of mine who called herself 'tolerant and open' said once to someone else in my presence: 'Dorothee always does strange things'.'

Dorothee has been asked if she has cancer because she makes her clothes from skin-coloured tights, with hair on uncommon places in forms that look genitals or beauty patches. Some galleries thought her work was ‘too bawdy to be exhibited’.

Dorothee has been asked if she has cancer because she makes her clothes from skin-coloured tights, with hair on uncommon places in forms that look genitals or beauty patches. Some galleries thought her work was ‘too bawdy to be exhibited’.

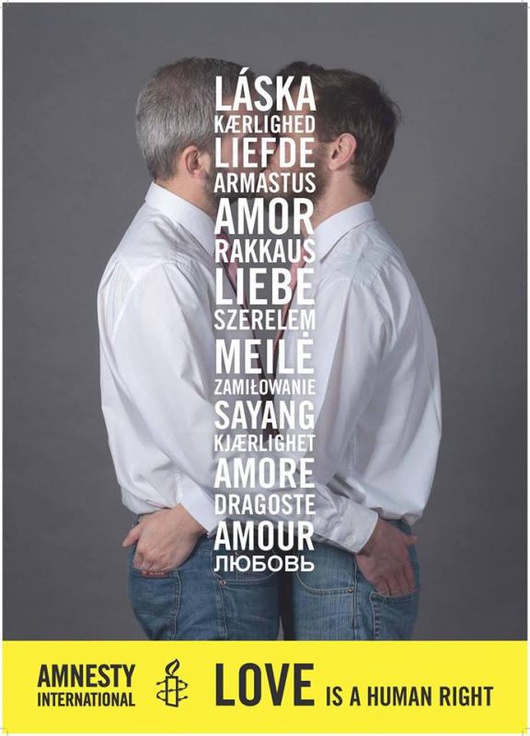

Kati, Budapest

'As a child I was interested in art, graphics and photography, but ended up a married biologist with three kids,' says Kati Holland. 'After my divorce, I finally came out to myself (about four years ago). I was going through an intense period of transition and self-exploration. The Buda drawing school is very tolerant and gave me the confidence to make the posters for my graphic design final exams. They show LGBTQ people kissing; the letters of the acronym are presented in the posters.'

'As a child I was interested in art, graphics and photography, but ended up a married biologist with three kids,' says Kati Holland. 'After my divorce, I finally came out to myself (about four years ago). I was going through an intense period of transition and self-exploration. The Buda drawing school is very tolerant and gave me the confidence to make the posters for my graphic design final exams. They show LGBTQ people kissing; the letters of the acronym are presented in the posters.'

The activist and queer artist grew up learning about taoism, yin and yang. She realised that the binary gender categorisation was an artificial, social construct. Hungarian society has a frightening homophobic layer, but people only think in heteronormative stereotypes and in the binary gender, she says. She didn’t fit the stereotypical expectation of a female. 'I felt I was a mixture of masculine and feminine, a humanist as opposed to a feminist. Accepting both masculinity and femininity is the way forward. I don’t accept patriarchy - but I don’t want to replace it with matriarchy.'