The Italian-French border: Land of fake news from the far-right

Published on

Translation by:

Annick Eisele

Annick Eisele

In France as well as in Italy, the far-right spreads false information to strengthen its local anchor. Incorrect statistics, racist newspaper articles and the propagation of fake news are uncovered in the second part of our investigation: Extreme Borders.

In his cabinet, the mayor takes his eyes off the big window which separates him from his office. His face seems relaxed, and the reflection of the blue sky can be seen in his blue eyes. His posture is assured and his suits is tailored. A confidence that is particularly typical of Gaetano Scullino since he has been elected in May 2019 as mayor of Vintimiglia, the first Italian town after the French border. A victory he owes to the support of the lists of La Lega and of the Fratelli d’Italia, two parties of the sovereign right. This support enabled the new mayor to defeat the centre-left incumbent mayor in the first round and to make a major come-back after losing the job in 2012, charged for complicity and conspiracy with a mafia organisation. A "big mistake" according to Gaetano Scullino, who was acquitted in 2016 in the final court of appeal.

If Vintimiglia is a commercial and touristic town according to the mayor, it's also the town where migrants who have been caught in the Alpes-Maritimes and denied entry by the French border police are brought to. The Italian-French border has been particularly busy since the beginning of the migration crisis in 2015. That year, more than a million people landed in Europe via the Mediterranean Sea. A number that has been decreasing considerably these past four years according to the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) which recorded 823,926 landing in Europe via the Mediterranean Sea during the last four years combined.

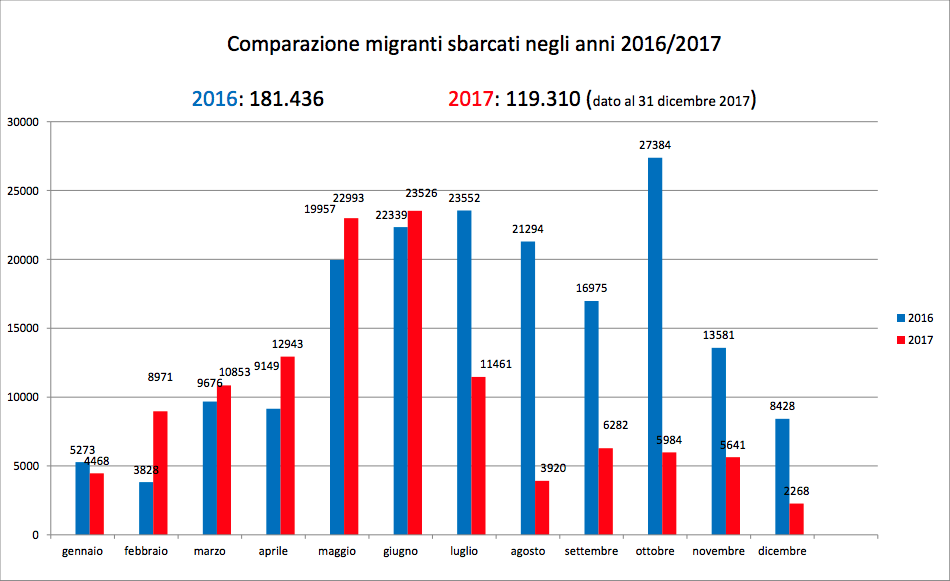

There's a similar trend in Italy, where the Minister of the Home Affairs has already recorded in a 34,24 % decrease in arrivals on its land in 2017 compared to 2016. According to Gaetano Scullino, this trend is largely linked to the policy of Matteo Salvini, Minister of Home Affairs from 2018 to 2019. On the other side of the border, the Rassemblement National (far-right party) candidate Philippe Vardon shared that vision on the day of the inauguration of his committee room in Nice in January 2020. A month before the first round of the French local elections, the candidate was claiming that "Salvini had reduced the number of migrants in Italy by 85% and the number of casualties in the Mediterranean See by half."

Let the figures do the talking

The numbers of migrants had been reduced well before Matteo Salvini was appointed Minister of Home Affairs in June 2018. The decrease began in August 2017, according the official document of the Italian Department of Home Affairs.

That trend is mostly due to the decisions of the previous government. "The number of landings on the Italian coast shrank during the summer of 2017, after the government of Gentiloni had concluded an agreement with the Libyan militia," explains Daniela Trucco, a researcher in political science and member of the Organisation for Migration in the Alpes-Maritimes. She refers to the agreement concluded in Rome between Italy and Libya in February 2017, to fight against illegal trafficking of migrants in the Mediterranean Sea. Simultaneously, the incumbent Minister of Home Affairs Marco Minniti established a code of practice in July 2017 for the NGO who plays an active role in sea rescue operations to restrain their action. One measure of the code was to complicate the departure of the boats for landings to decrease gradually.

For the researcher, the real impact of Salvini's policy touches on the legal status of the entrants. "There are people who had already been integrated within the Italian reception system and who have been excluded from it. The first result of Salvani's policy was to create illegality." Before 2018, Italy was offering a protection to people who didn't meet the criteria stated in the Geneva Convention, but who, according to the SPRAR (Protection System for Asylum Seekers and Refugees) were in danger in their home country. 25% of asylum seekers benefited from this protection in 2017. This option was eliminated by Salvini's decree, which reduced the ways to obtain protection in Italy and allowed expulsions to be increased.

That abrogation left 25% of asylum seekers without protection in 2017.

"With the arrival of the migrants, Vintimiglia was an occupied town."

This is a political line the mayor of Vintimiglia, who wishes to preserve the touristic and commercial image of his town, agrees with. He comments: "We're 30,000 people and we cannot pay the price of several migrants in town, both in terms of credibility and of safety." He adds: "With the arrival of the migrants, Vintimiglia was an occupied town. Lybians, Tunisians, Moroccans and Syrians have a different mentality."

If Gaetano Scullino now considers that there are "no migrants in town anymore," the number of people who are being turned away at the border with Menton is still high. "Today, we counted 45 people, including someone under-aged," said Adèle, member of Kesha Niya, an organisation at the border which had been exposing three years of regular police violence. According to their observations, between 500 and 2,000 people are turned away each month. For the young woman, it would be more accurate to talk of an "invisibilisation" rather than of a disappearance of the migrants in Vintimiglia. After the numerous dismantling of migrants camps, the Red Cross camp,Campo Roya, is since April 2018 "the only place where those people can find help, in a six-kilometer radius around town," adds Daniela Trucco.

The re-information of the far right

On the French side, disinformation is also one of the methods used by the far-right to discredit people who are in favour of welcoming the migrants (see Episode 1 of the series). Very active on social networks during the campaign, the Rassemblement National (far-right party) candidate for Menton Olivier Bettati shared in July 2017 on his Twitter account a fake news published by the weekly publication Valeurs actuelles reporting the imprisonment in Grasse of the "migrants smuggler" Cédric Herrou in 2017. The farmer was actually in custody before being released - a nuance which must have escaped Olivier Bettati. Another vexing element for Bettati, still in July 2017, is "a proof of fake applications for asylum" according to him, who hasn't hesitate to call the farmer of "the last link of a smugglers mafia which accumulates huge wealth thanks to a Europe which is wide open." The fake documents were only certificates that the organisation Roya Citoyenne was preparing to help the migrants with their applications for asylum.

Find out more: Migrant Crisis: Liberty, Equality, Offence of Solidarity

To support his words, the candidate for the local elections has gone to Breil-sur-Roya to film "100 migrants who were about to take the train for free with the smuggler Cédric Herrou." To reiterate the facts, on the 16th of June 2017, around 80 migrants took the train to go to the Nice Prefecture to ask for asylum. Train tickets were paid by the town, a decision "not approved by everyone", comments the Mayor of Breil-sur-Roya, André Ipert.

"Poor creature just passing by and looking for white women"

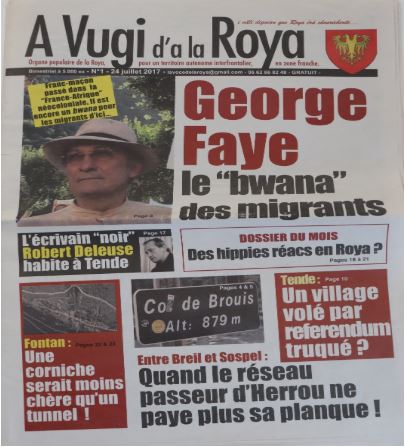

Alongside the online spread of fake news, the libellous newspaper A Vugi d’a la Roya ("The Voice of la Roya"), which Cafébabel got hold of, was circulating in the Roya Valley. A newspaper written by no other than the fascist activist Rodolphe Crevelle (see Episode 1 of the series), who had been convicted several times for "hate speach". The newspaper which prints 5,000 copies was attacking the refugees and their helpers. An "highly polemic paper with ad hominem attacks and offensive remarks," according to the public prosecutor who has launched an inquiry after the publication of the first issue.

It's true to say that Crevelle wasn't very subtle. In one of his articles, the far-right activist gave a long speech about the migrants. "The poor creatures are only passing by looking for modernity, easy life and white women, who are obviously the main stimuli for an immigration for the festivities like the tragic consequence of wars, dictatorships and poverty that have left no trace on these strapping lads who still full of sap, super connected, and who have crossed the oceans as can be done at this age when you have a Marylin Monroe in your head and masturbate four times a day while streaming."

If A Vugi is really on the far-right, it has no official relations to the Rassemblement National, and the boundary between these different players can be blurred as shows the support of Défendre la Roya far-right association with ties to the RN, propelled by Olivier Bettati.

A few days before the local elections, the far-right still instrumentalises the migrants. On the 2th of March, Philippe Vardon wrote a tweet about the migration crisis in Lesbos: "Check out this poor refugees, running away from war and poverty by throwing Molotov cocktails at the Greek border while shouting "Allah Ackbar" about a video spread by far-right supporters. The video, which doesn't show any Molotov cocktail, was taken by a migrant when clashes have started at the Turk border and when the police officers charged migrants with tear gas in reitiration to them throwing stones at them. "Massive immigration only leads to chaos," commented Philippe Scemama, Philippe Vardon co-candidate for the local elections.

In a survey before the first round of the elections, the RN candidate was credited with 13% of vote intentions against 49% for the incumbent Mayor Christian Estrosi. Influencing public opinion with unverified information is still controversial with the Alpes-Maritimes constituents. In Vintimiglia, Gaetano Scullino didn't need to make his campaign about migration. "A town where right parties have been in power more often and longer than the left," analyses Daniela Trucco, who claims that the impact of the election of the Mayor supported by the Lega to the management of the migrants at the border was minimal, as "the reception system was already functioning well at the time of the elections."

This article is the second one of the three-part series: Extreme Borders. Through his investigation at the Italian-French border in collaboration with the EHESS, journalist Safouane Abdessalem discovers the electoral strategies of the far-right in the 2020 local elections. Overt and covert ties with nationalist activists, publication of fake news about migration, proceedings against local charities, to what length is the far-right prepared to go to attract votes? Discover it in the next episode of this series.

Cover photo: Former border point in Menton © Safouane Abdessalem

Translated from Frontière franco-italienne : terre des fake news de l'extrême droite