The hunting ban: humane or undemocratic?

Published on

This week the British High Court will definitively decide whether the fox-hunting ban will be upheld. But more is at stake than foxes

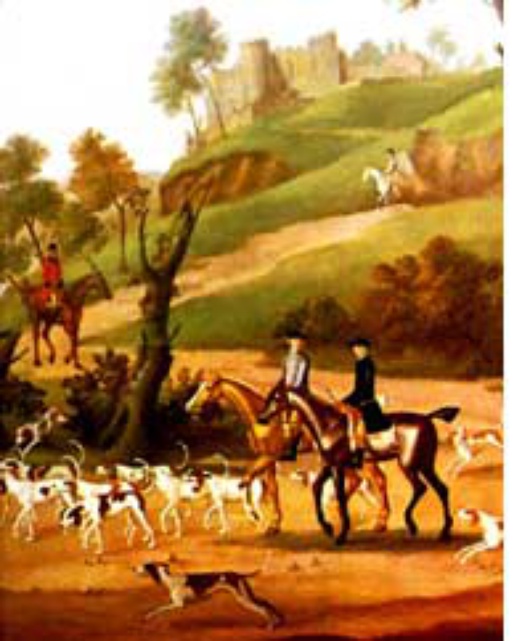

Fox hunting and so called blood ‘sports’ are often justified by those who practice them on the grounds that they are traditions that are woven deep into the fabric of our societies – from the Corrida in Spain, via La Chasse in the Loire valley to the traditional ‘Boxing Day Hunt’ in the UK. Yet to consider such acts ‘sport’ is a clear misnomer as this term connotates a level playing field for the various protagonists. Such practices are ‘rituals’: pre-ordained demonstrations of man’s evolutionary superiority over beast. But moral arguments aside, the manner in which the UK hunting ban was brought in has wider implications for British parliamentary democracy.

Fox hunting and so called blood ‘sports’ are often justified by those who practice them on the grounds that they are traditions that are woven deep into the fabric of our societies – from the Corrida in Spain, via La Chasse in the Loire valley to the traditional ‘Boxing Day Hunt’ in the UK. Yet to consider such acts ‘sport’ is a clear misnomer as this term connotates a level playing field for the various protagonists. Such practices are ‘rituals’: pre-ordained demonstrations of man’s evolutionary superiority over beast. But moral arguments aside, the manner in which the UK hunting ban was brought in has wider implications for British parliamentary democracy.

The Parliament Act

Unlike some European states (for example Sweden), for a bill to become law in the UK it must pass through both the elected lower house, the House of Commons, and the upper legislative house, the House of Lords. This allows the upper house to scrutinise and consider government initiatives prior to them becoming law and, if they so wish, to strike them down. An exception to this rule is when Members of Parliament choose to bypass the Lords by invoking the Parliament Act (passed in 1911 and refined in 1949). However, the Act itself was never approved by the Lords and its consequent 'illegality' is currently the basis of the legal challenge brought by pro-hunt campaigners in order to stop the ban on hunting coming into force. They argue that the 1949 Parliament Act was not correctly legislated and hence it is not law. Last Friday (January 28th) the High Court rejected their complaint and this decision is to be appealed this week, but it is more than likely that the appeal will fail and the ban will come into force in March this year.

In using the Parliament Act to pass the ban, the government has effectively ignored the democratic process and used the weight of its significant parliamentary majority to strong-arm this policy through. Interestingly, since its amendment in 1949 the Act has only been used four times, yet three of these have been since the current government took office in 1997. This is a worrying trend, particularly bearing in mind the motivation behind its use: the UK ban on hunting has been on the agenda for five years now and it must be asked if, with an election looming, it has been made law to show zeal for reform rather than for any great moral reasons. In a democratic process, actions ought to be scrutinised and actions of governments open to censure. Events in Ukraine last December showed democracy in action: the manner in which the hunting ban has been forced through shows that even in apparently more established states, democracy has its limits.