The Hidden Side of TTIP, with Philippe Lamberts

Published on

Translation by:

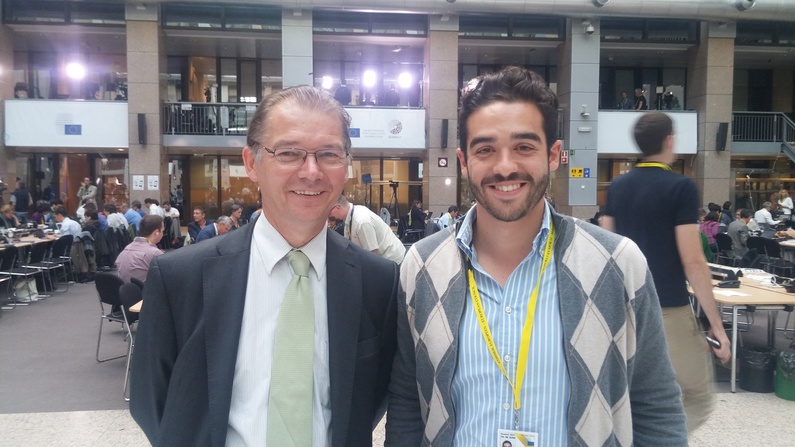

Abigail WatsonPhilippe Lamberts, Co-Chair of the Group of the Greens/European Free Alliance at the European Parliament, is one of the most outspoken critics of TTIP in European politics. But why exactly is this MEP so opposed to an agreement that is meant to represent a step forward for the European Union? We get answers under the neon lights of the European Council.

cafébabel: How would you, personally, define TTIP?

Philippe Lamberts: The Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership, or TTIP, is actually a project that took root several decades ago. Backed by the heads of large American and European businesses, it aims to combine the European and American markets, creating one huge transatlantic market.

As a matter of fact, however, TTIP's objective is more far-reaching than this would suggest. The aim is to harmonise social, environmental, health, tax and democratic standards in response to pressure from businesses. In other words, motivated by the desire to increase their own profit margins, these businesses are urging the Member States to harmonise their standards and reduce them to watered-down versions. It is hardly surprising, therefore, that support for this project mainly comes from businesses driven by a single objective: maximising their short-term profits.

cafébabel: But a great many people see TTIP as a brilliant opportunity for the European Union. Don't you agree?

Philippe Lamberts: At any rate, I strongly oppose the project as it stands today, because the treaty's architectural framework is designed to establish a large market wherein the standards put in place by democracy will be all but sold off in an auction engineered by the multinationals, who will always be able to hold the signatory states to ransom over investment and employment.

We are all well aware of the United States' key demand - to open up the European market to a wide range of products that are currently banned or restricted, such as those sold by American agro-businesses (GMOs, hormone-treated beef, etc.). In fact, the real aim of this treaty is to allow anything and everything based purely on the logic of commercial gain, even if that means weakening our democratic standards and sacrificing social dialogue. It's completely unacceptable!

Can you explain how the Investor-State Dispute Settlement (ISDS) instrument works? And why do some people see it as an attack on democracy?

Philippe Lamberts: Without a doubt, this settlement mechanism for disputes between investors and states, in other words, between businesses and states, is emblematic of the spirit of TTIP. It's a legal measure that enables companies to attack any public authority, from a state to a local municipality. In today's society, such matters can already be resolved at a traditional court. The difference is this: the TTIP framework will establish a special private court, known as an arbitral tribunal, composed of three judges who, more often than not, will be business lawyers. This gives rise to a rather unusual system in that it falls outside the general law system of any state, which is simply absurd considering that a business is answerable to the law, just like any other legal entity, and that it is normal practice for companies to use traditional courts. Another particularly unsettling aspect is the system's one-way structure: only businesses are able to attack a state, not the other way around.

To put it more clearly: this is a system that would make it possible for a business to attack a public authority on the grounds that its potential returns may be affected by a particular measure. It is nothing more, therefore, than a means of ensuring that the right to profit is enshrined as the ultimate right to be held above all others. For example, you still have the right to health, as long as this right does not affect the revenue of Phillip Morris, a cigarette manufacturer.

If encouraging transatlantic trade were indeed the true objective of TTIP, then removing the ISDS clause from the agreement should not pose a problem. The United States and all European countries are constitutional states that have courts; if a company operating in these states believes that its interests have been jeopardised, it can always choose to bring a complaint before the court. But by questioning ISDS, we suddenly seem to have cut to the heart of the issue, going by the reaction of all the pro-TTIP parties. The topic is downright taboo!

cafébabel: In all honesty, do you think it's likely that an agreement will be reached on TTIP in the not-too-distant future?

Philippe Lamberts: My gut tells me that we will win this battle, even if it’s not yet clear how. Either the wave of opposition in Europe and the United States will continue to rise and become so large as to disrupt the talks, or the talks will be concluded but the agreement will give way to the pressure of civil society and will be rejected as soon as it is brought before the public. You see, the complete text will only be made available once the talks are over, before the agreement is ratified.

And actually, the more I debate with pro-TTIP parties, the more I realise that they have no valid argument. They haven't got a leg to stand on. They are just betting on the fact that people won't know enough. Now that the matter is being brought before civil society, people are well aware that this agreement is not to their advantage.

That said, even if we succeed, it is my opinion that the logic of TTIP lives on in a range of measures proposed or already introduced by the European Commission, even if the agreement itself is not in force. It is clear that those in power in Europe today are, for the most part, of a single mindset; a mindset that sees trade and deregulation as the solution to all our problems. We’re at a tipping point, and so it’s important that we win this battle. But this victory alone will not be enough if that single mindset is to be reduced once and for all to what it should be; an intellectual pipe dream that never should have seen the light of day.

Translated from La face cachée du TTIP avec Philippe Lamberts