The Greek case: the EU, referenda and democracy

Published on

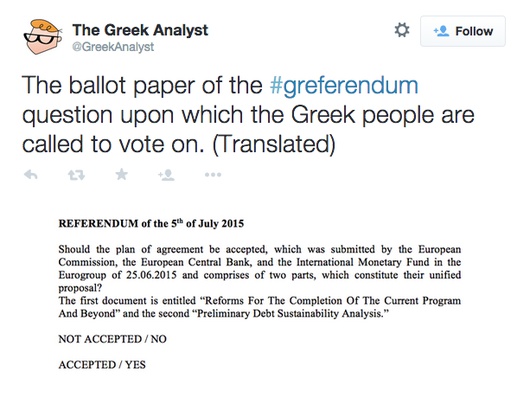

On July the 5th, the Greek people will answer an as yet undefined question regarding the country’s debt crisis and whether it should agree to a fresh round of austerity. Yet, with the European Central Bank (ECB) deciding to limit its emergency lending, vital for Greek Banks’ liquidity, is this referendum a democratic sham?

Alexis Tsipras’ Syriza-led government, elected on an anti-austerity platform, has played a terrible hand not too badly. After it became clear that the pro-austerity EU members, such as Germany and Finland, wouldn’t accept the latest deal on the table, Tsipras called a referendum.

The question to be posed, summed up perfectly by Channel 4 Economics Editor Paul Mason, is, “will you sign up to the economically illiterate, forever indebted plan offered by the IMF/EU or give us a democratic mandate to resist it, even if they crash our banks.”

(update: a reported translation of the question that will be posed in the referendum)

Either way, there will be pain for Greek citizens, self-inflicted or not. Others aren’t convinced of the democratic credibility of this vote, especially when the question isn’t clear.

Either way, there will be pain for Greek citizens, self-inflicted or not. Others aren’t convinced of the democratic credibility of this vote, especially when the question isn’t clear.

The conservative business paper Naftemporiki writes: “The vote on an agreement that has not yet been concluded and which entails dozens of tax measures and other complicated issues, the details of which we don't know and can't understand can't be formulated in one clear question. … To enable the citizens to assume responsibility, the government - and above all the rest of the political world - should explain responsibly and honestly what the consequences of a Yes or No vote will be.”

The likelihood is that, however the referendum question is framed, Greek citizens are shaping up to vote against the creditors’ proposals, even if it could mean an eventual exit from the Eurozone.

It would be an extraordinary turn of events, which some commentators have dubbed a ‘Sarajevo moment’. Over the history of the European Union, even when national referenda have led to a ‘no’ vote, from the ratification of various treaties to joining the single currency, the European project has gone on. This could be first referendum result to go truly against the grain.

Yet how are referenda in general viewed across Europe, when the EU is concerned?

Though Poland hasn’t had any referenda related to the EU since its accession in 2004, our Polish editor Katarzyna Piasecka explains the view from Warsaw: “Young Poles are enthusiastic about referenda as a democratic way of taking social and political decisions, but older generations, remembering the communist era, remain distrustful about their credibility. In Poland, referenda are quite common, organised on regular basis and often demanded by society.”

As for Deutschland, our German editor Katha Kloss explains: “Since the experiences of the Weimar Republic the German Grundgesetz (sort of our constitution) doesn’t allow nationwide referenda, except for geographical issues such as pooling federal member states together or apart. Instead of the ‘wisdom of crowds’ we prefer to speak about so called Schwarmdemenz – the dementia of crowds, a popular term nowadays referring to active participation on social media. The Germans have never been asked for their opinion directly on the EU case. But voices are getting stronger in favour of more direct participation here too. This is why Germans will follow the Greek referendum on 5th of July with fear and admiration.”

In France, the last referendum took place in 2005 and concerned the treaty establishing a new constitution for Europe. 54,67% or 15,449,508 people, voted “no.”

In France, the last referendum took place in 2005 and concerned the treaty establishing a new constitution for Europe. 54,67% or 15,449,508 people, voted “no.”

Our French editor Matthieu Amaré elaborates on why the “no” vote was ultimately pointless: “Asking the population about an issue is not a problem, on the contrary it embodies the idea of democracy, and I’m cool with it. Nevertheless, there is always a context and a way to phrase the question. Let’s take the context first. In 2005, the referendum allowed parties to campaign for the “yes” or “no” vote. In the end, it’s a political matter and people are answering the question, not because it will affect us in some way, but because they support the opinion of their candidates.

“Secondly, the question: Seriously, did anyone read it carefully? It’s more complicated than the cash surplus of an offshore company selling bananas in the South of Jersey. Ratification, treaty, constitution… too many technocratic words for an anti-establishment answer. But the government did not care. Two years after the No vote, they decided to not listen and put all the measures into a treaty, signed in Lisbon. Does this ring a bell?”

Since 1936, Spain has had 6 national referendums. The last one saw a “yes” vote in 2005 to decide if the country wanted to adopt the European Constitution. Regarding Greece, our Spanish editor Ainhoa Muguerza notes, “A referendum is a sign of democratic health and an exercise of freedom of speech for citizens. However, there are some aspects, especially when it concerns an economic situation that unfortunately you need to have technical and specialist knowledge to make one choice or another.”

As for the UK, there have been local referenda but only two votes have covered the entire country. While there will be a vote on the UK’s membership of the EU in 2017, on the whole, it is votes in Parliament that tend to decide things, perhaps heeding former Tory Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher’s view that referenda are "a device of dictators and demagogues."

This cynicism might be justified by the example of the most recent referendum (2011) in Italy, which packaged together a range of issues from "nuclear energy to public ownership of water, as well as a law that legitimised certain delays for politicians to appear at a court hearing. In Italy, referenda can only take place to repeal a law and these laws were ultimately repealed," explains our Italian editor Lorenzo Bellini. "Since 1995, several referenda have taken place, but they didn't reach the quorum of 50% (except the 2011 one)."

For Tsipras and Syriza, a referendum is the only card they have left to play - despite the technical nature of the issue and the inevitability of a negative outcome for the Greek people, however the vote swings. Onto the 5th of July we go.