The Great Turkish Trek

Published on

Every culture starts its stories in a different way. In Iran, they start with “Yeki bood, yeki nabood” ("There once was, there once was not...”). The Scots say “In the days of auld lang syne.” In this story, I begin with the Greek “Μια φορά κι έναν καιρό” - "Once, in another time..."

Once, in another time, when air travel was still unaffordable for the average migrant family, convoys of Western European Turks traveled like migratory birds each summer in baking, packed cars towards the motherland. Or rather, the stepmotherland - after all, some had lived in Europe their whole lives. Within a period of six weeks (the summer vacation of most public schools), they visited their relatives and ancestral villages, conducted epic shopping sprees, and sometimes even managed to squeeze in a beach vacation, depending on their budget. Over the decades, these annual journeys have become a true subculture among Turkish migrants in Western Europe.

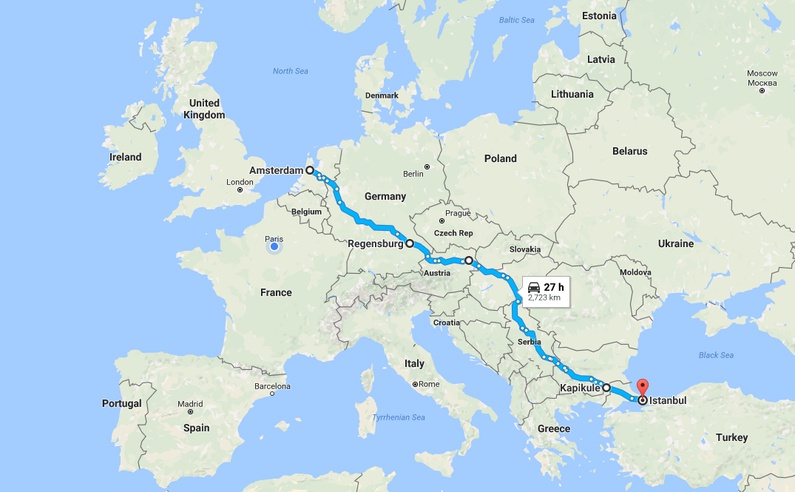

A universe of received knowledge, based solely on observations and experience gathered by hundreds of thousands of people, forms the cement of this culture. My uncle, for example, knew the entire route from the Netherlands to Turkey by heart. Not once did we ever catch him glancing at a map. He recognized meadows in Germany, knew exactly which Austrian parking lots offered the most stunning views of the Alps, and carefully guarded the secret of which gas stations had the cleanest toilets. He even claimed to know certain customs officials personally, although none of them ever seemed to greet him back.

I myself often took the role of navigator as my father would drive. The road map folded on my lap, I closely followed our progress on the autobahns and mountain passes. I notified my dad of distances, upcoming gas stations and (if I knew them) historical anecdotes about the region. In the back of the van, my mother and sister killed time eating chips, breaking records on the GameBoy, or catching up on sleep.

Back home, always in the first week of September, we’d visit friends and exchange fresh anecdotes about this year’s trip. He who had the most captivating story would first patiently listen to everyone else, meekly sip his tea and nod with feigned admiration; waiting with the patience of a card player who knows he has a winning hand. Then, nonchalantly, he would throw his awe-inspiring story onto the table, leaving his rivals dazed and impressed.

Trials and tribulations

The history of the Great Turkish Trek can be divided into two periods: before and after the war in Yugoslavia. After the outbreak of the war, we could no longer use Tito’s famous highway of “Brotherhood and Unity” (autoput bratstvo i jedinstvo). After all, both the ideology and the highway itself now laid in ruins. The alternative was to drive through Hungary and Romania, down to Bulgaria. A few adventurous souls still ventured into Serbia. In any case, the trip always began with a predictable and smooth ride on the Autobahns through the Ruhrgebiet towards Regensburg. We often spent our first night around Vienna, and Hungary would loom as the first post-Communist country. Indeed, before Hungary became an EU member, the Hungarian-Romanian border was often the first real test.

The history of the Great Turkish Trek can be divided into two periods: before and after the war in Yugoslavia. After the outbreak of the war, we could no longer use Tito’s famous highway of “Brotherhood and Unity” (autoput bratstvo i jedinstvo). After all, both the ideology and the highway itself now laid in ruins. The alternative was to drive through Hungary and Romania, down to Bulgaria. A few adventurous souls still ventured into Serbia. In any case, the trip always began with a predictable and smooth ride on the Autobahns through the Ruhrgebiet towards Regensburg. We often spent our first night around Vienna, and Hungary would loom as the first post-Communist country. Indeed, before Hungary became an EU member, the Hungarian-Romanian border was often the first real test.

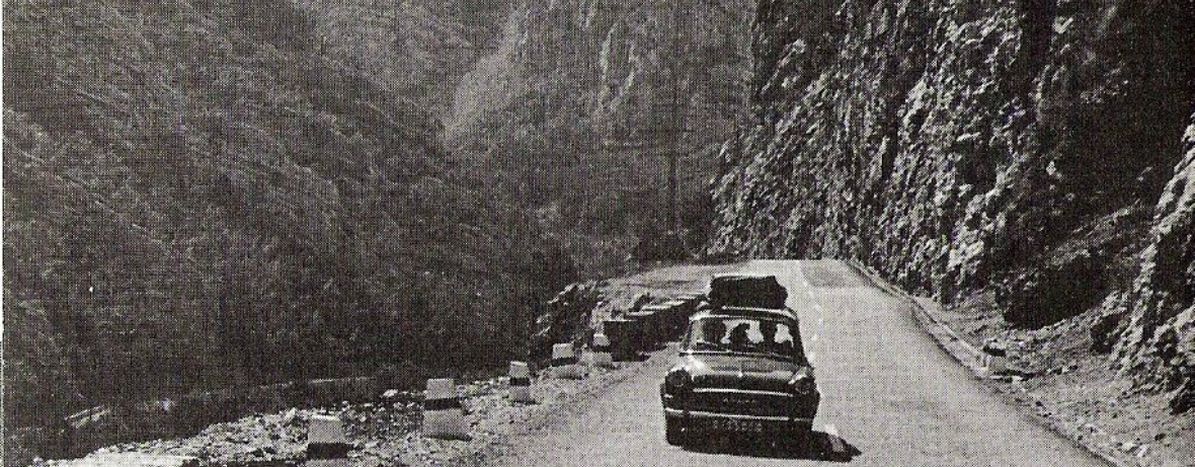

Our camper van trudged on unperturbedly on the shabby Romanian roads, along fearsome ravines without guardrails and through picturesque valleys. This idyllic landscape was often marred by Romanian police officers and their extortionate checkpoints. “The Bulgarian cops are all mobsters,” they would cry out in chorus, before showing us a radar device that was clearly preset at 200 km/h – a speed our overloaded camper van had no hope of reaching.

“Wieso zwei Hundert, Kollega?” my father asked, presuming that the cop would speak basic German. The chubby Transylvanian police officer now began to cackle in Romanian and wave his handcuffs, at which my father lost his temper and angrily got out of the car. What frightened me was that my mother begged my dad: “Honey, please stay calm.” (I already imagined four tattered bodies laid all twisted over each other, while my dad with his bloodied shirt drove away from the crime scene. “Honey, what happened?” ... “Oh nothing, sweetie…”) Fortunately we Turks did not have to leave a trail of destruction in the Balkans again. Dad had simply refused to pay the thinly veiled bribe and threatened to contact the Dutch consulate and hire a lawyer in the first town.

Encounters

The last mile is the longest. Bulgaria was a country where we could neither read the road signs, nor understand the implicit traffic rules. Oncoming cars would flash their lights, and the drivers would tap on the dashboard. Later we learned this was form of solidarity: a signal that further on, the police were extorting unsuspecting motorists. At the first Bulgarian traffic checkpoint, another chubby and mustached gentleman would point northward and exclaim: “The Romanian officers are all mobsters!”

The last mile is the longest. Bulgaria was a country where we could neither read the road signs, nor understand the implicit traffic rules. Oncoming cars would flash their lights, and the drivers would tap on the dashboard. Later we learned this was form of solidarity: a signal that further on, the police were extorting unsuspecting motorists. At the first Bulgarian traffic checkpoint, another chubby and mustached gentleman would point northward and exclaim: “The Romanian officers are all mobsters!”

As we did not read the Cyrillic alphabet, we had to slow down for the road signs so I could look in my notebook and assemble the correct letter combinations. With some long names of towns like Стара Загора (Stara Zagora) or Велико Търново (Veliko Tarnovo), we would almost come to a standstill. The borders were always stressful. I remember a portly Bulgarian border cop, peaked cap on the crown of his head, and old sweat stains under his armpits. He opened the trunk of the car in front of us and rummaged around, took out a can of Coca-Cola and poured its contents in his gullet in one go, slamming the trunk back down again and walking on without batting an eyelid.

We undoubtedly had our most interesting experiences in the former Yugoslavia. Its reputation had been good among Turks: the roads were better, state officials more reliable, the alphabet legible, and well, the Yugoslavs had kind of still remained a little Ottoman, right? But even during the war, Dad became seized with a quietly maniacal urge to drive through Serbia. Even far from the front, one could feel the consequences of the war.

Stopping for gas in Eastern Serbia in 1996, I once saw a boy tap on the window and point to a pack of soggy cookies that had been melting on the dashboard for days. I stared at his emaciated chest and protruding ribs, before I finally realized this hungry kid was scrounging for food. In perfectly Dutch fashion, I took exactly one cookie from the pack and handed it to him. He wolfed it down and came back, clearly not satisfied. My father saw the whole scene and told me to give him the whole pack of biscuits. The desperate expression on his face was something I had never seen before, and it still haunts me.

Criminal

As far as I know, I have never knowingly broken a law, with one exception. The first summer after my eighteenth birthday, I thought I could impress my cousins in Istanbul by smuggling marijuana to Turkey. After all, it was decriminalized in the Netherlands, and in my teenage years I had bragged to them each summer about it.

As far as I know, I have never knowingly broken a law, with one exception. The first summer after my eighteenth birthday, I thought I could impress my cousins in Istanbul by smuggling marijuana to Turkey. After all, it was decriminalized in the Netherlands, and in my teenage years I had bragged to them each summer about it.

So, in June 1999, a few days before the annual departure, I bought a few grams of Purple Haze at our local coffee shop. At home I brooded about how to best hide the stuff on the long trip to Turkey. I remembered a documentary that showed how Colombian cartels smuggled their drugs across international borders by hiding it in big packs of coffee, so the dogs could not detect the stuff. Eureka! This was a unique opportunity to get rid of my reputation as the library nerd. Now, I would cruise down the Bosporus boulevards in shiny convertibles, half-naked women massaging my neck and calling me ‘Escobar’. So I bought two packs of instant coffee, emptied both into a plastic bag and buried the weed bag deep inside. I tied it down and placed it at the bottom of my suitcase, with my underwear right on top.

Thanks to the open EU borders, throughout the trip I never worried about the law: by 2000, there were no real passport checks, let alone luggage controls. Upon arrival at the Bulgarian-Turkish border, I snickered. The Bulgarians never checked outgoing cars, and the Turks would obviously welcome their brethren with open arms. At the break of dawn, we stopped at an unshaven, sleepy Turkish customs official in a rickety booth. The man stamped our passports languidly and barked: “Go park your car over there.” My dad froze. After having undergone all the insults and corruption in Romania and Bulgaria, this lack of courtesy, of all places in his homeland, was the final straw.

“No,” he snapped, “you ought to say, ‘Would you please your car over there, Sir?’” The officer turned his head so slowly towards us, I noticed only later that his jaw had dropped in surprise.

“What. Did. You. Say? You telling me how to do my job? Park your car there, and fast! We are going to give you a thorough search.”

At this point I was having an out-of-body experience. Of all people in the world, did my father really have to provoke this guy? I wasn’t afraid of the Turkish police: they would probably confiscate the weed, perhaps scare me a bit, and finally let me go with a warning. But if Dad found out his goody-two-shoes son had smuggled enough weed to be stoned through much of the holiday, his wrath would have been epic. Two Turkish customs officers, clearly annoyed at having to work so early in the morning, walked up and ordered us to take out and open all the bags in the car. Knees trembling, biting my lip, I stood there while the officers pointed at my bag and inquired about its contents. I whimpered: “Underpants, sir.” They looked at each other and grinned. “Need that much underwear for your holiday?”

“Sometimes I wet the bed, sir,” I improvised. He burst out laughing and nodded jovially: “Fine, put it all back and have a good trip.”

Upon arrival in Istanbul, I opened the bag and found out that all my clothes reeked of weed. Otherwise, I don’t remember much of that holiday.