The ghosts of Hungarian nationalism

Published on

Translation by:

rachel thomas

rachel thomas

In Romania, the Magyar, or ethnic Hungarians, are once more cultivating a strong sense of nationalism. And they are not alone.

On January 10th the Romanian Minister for Culture, Mona Musca, banned any further showing of the Hungarian docu-film ‘Trianon’ in Romania on the basis that it was chauvinistic. Although the film has since been ‘legalised’, fears that its take on Hungarian history would provoke irredentism in Transylvania, a strongly Magyar area of Romania, are proof of the ongoing friction in the region.

On January 10th the Romanian Minister for Culture, Mona Musca, banned any further showing of the Hungarian docu-film ‘Trianon’ in Romania on the basis that it was chauvinistic. Although the film has since been ‘legalised’, fears that its take on Hungarian history would provoke irredentism in Transylvania, a strongly Magyar area of Romania, are proof of the ongoing friction in the region.

An uncomfortable portrayal

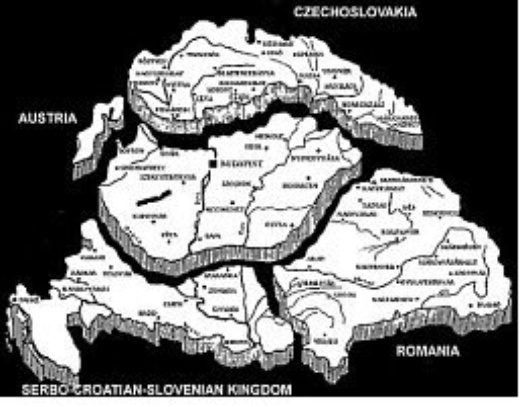

‘Trianon’, directed by Gábor Koltay and inspired by the works of the Hungarian historian Erno Raffay, depicts the lives of those Hungarians left outside the borders of modern Hungary following the Treaty of Trianon, which was ratified on June 4th 1920 in the French palace of the same name. The treaty, which aimed to create a lasting peace between the victors of the First World War and Hungary, forced the latter to concede Croatia to Yugoslavia, Transylvania to Romania, and Slovakia to Czechoslovakia.

Today, there are nearly 1.5 million Magyar living in Transylvania and, last December, a referendum was held in Budapest on whether Hungarian citizenship should be offered to these and other ethnic Hungarians living outside the borders. The proposition, put forward by the conservatives, was naturally opposed by Hungary’s neighbouring governments and in the end failed due to low voter turnout.

The nationalist priest

Laszlo Tokes, a Romanian priest of Hungarian origin, expressed his surprise at the ban prohibiting the screening of the Hungarian director’s film. The priest, whose harassment for his anti-communist discourse was the spark that fired the Timisoara Revolution of December 1989, recalled, in an interview with the newspaper Evenimentil Zilei on January 14th, how ‘Trianon’ had been screened in cinemas all over Romania as late as the end of last year, in spite of the electoral campaign at the time. “No one had at that point banned the film in Transylvania, where every party was dependent on the Hungarian people’s vote” affirms Tokes, who was one of the people interviewed by Koltay for his documentary. Tokes, who is known for his nationalist and autonomist sentiments, stresses, “In the film I spoke of the injustice of the Treaty of Trianon, which took away two thirds of Hungarian territory. The Hungarians are indigenous to Transylvania and should never be considered a minority.” He goes on, “The Hungarians are still suffering from the consequences of the Treaty of Trianon. In the last 15 years the number of Magyar in Transylvania has dropped by about 200,000 people. If things continues at this speed, it will be an ethnic catastrophe”. Tokes has, however, expressed the hope that the European Union could give Hungarians the right to survive because, “In a Europe without borders we cannot ask for territory, but we do want to have the right to determine our own autonomy.”

But it isn’t just the Magyar

What, if anything, does he mean by autonomy? Another Transylvanian ethnic minority, the Szeklers (Secui in Romanian), are also of Hungarian origin and have placed a claim to autonomy on the grounds of ethnicity to both the Budapest and Bucharest governments. This was contested by the Romanian president Basescu, who on February 17th ruled that no minority would be any more autonomous than the other while he remained in office. The Szeklers want recognition of their own identity and have called for territorial autonomy but the Romanian government is more disposed to giving them administrative autonomy within a process of decentralisation. In such a struggle for territory as this, particularly taking into account the country’s recent past which has been characterised by deep conflict, Romania has earned itself model status regarding how the rights of minorities are respected. With 17 ethnic minorities, all of which are represented in the Bucharest Parliament, the country has come out on top with the motto of celebrating variety and difference. After the fall of the communist regime in 1989, all the national minorities have had their rights recognised but, up until now, never defended. In places where the ethnic minority constitutes a majority at a local level, the use of the native language in education, law and administration or in its institutions is often also bilingual. Transylvanian cities the street names, signs in the area and in its institutions are written in Hungarian, German and Romanian.

In spite of these efforts there are still problems regarding social integration – particularly of the Roma - and there are still protests by minorities. The greatest and, in certain aspects, the most worrying of these problems concerns the Hungarian minority in Transylvania. The most worrying because there are fears that Hungary will seek to reclaim the territory it lost after the First World War, as it did in alliance with the Nazi and Fascist regimes in the 1930s.

Translated from L’Ungheria e i fantasmi del revanscismo