The future’s a bitter pill to swallow in Prague

Published on

Translation by:

jessica adler

jessica adler

The audacious design of the new National Library in Prague unleashes intense debate

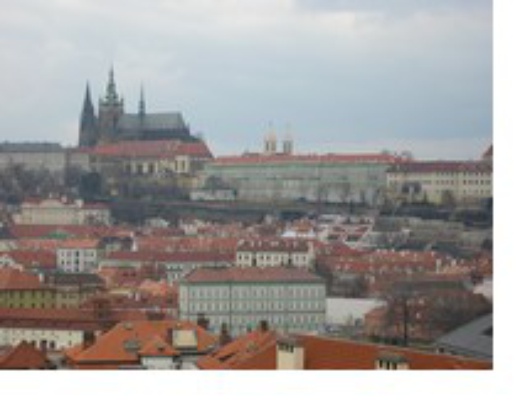

For some, it’s a giant, futuristic machine. Others see it as a sea creature, sinuous and crowned with a brightly-coloured shell. Jan Kaplicky, its designer, prefers to call the controversial project that is the new Czech National Library 'the eye over Prague', and he defends it as the 'antidote to the conservatism that impregnates the country’s architecture.'

'The authorities sometimes don’t treat with respect anything built after 1900. They’re worried about a small cornice in any apartment of which there are millions here, in Budapest, in Vienna and God knows where else,' he declared recently to Radio Prague. 'They’re obsessed with being Czech,' he added in the same interview.

'The authorities sometimes don’t treat with respect anything built after 1900. They’re worried about a small cornice in any apartment of which there are millions here, in Budapest, in Vienna and God knows where else,' he declared recently to Radio Prague. 'They’re obsessed with being Czech,' he added in the same interview.

A pyrrhic victory?

Kaplicky went into exile in London in 1968, faced with the prospect of 'not being able to exhibit, design or do anything else' under the communist regime, following the entry of Soviet tanks into Prague. Now, after gaining a significant international reputation, he is a sort of prodigal son in his country. His model of the National Library, which must be built by 2011, was awarded the highly sought-after commission over the 355 entries from architects from all over the world.

However, some high-profile critics, such as the director of the Czech National Gallery, Milan Knížák, have already voiced their opposition to the project. Many Czech citizens have yet to be convinced by the library’s spectacular, futuristic silhouette, to the extent that there are doubts about whether it will, in fact, end up being built.

The winning project plans to introduce surprising innovations such as a modern automated withdrawal system for the 350, 000 volumes that will be available. The books will be hidden away in an underground store and a central lift will take them, in under five minutes, into the hands of the person who has requested them. Most of the 50 metre-height of the building will provide a spacious feel which, according to Kaplicky, will encourage people not just to read but also to choose the library as a meeting point.

The winning project plans to introduce surprising innovations such as a modern automated withdrawal system for the 350, 000 volumes that will be available. The books will be hidden away in an underground store and a central lift will take them, in under five minutes, into the hands of the person who has requested them. Most of the 50 metre-height of the building will provide a spacious feel which, according to Kaplicky, will encourage people not just to read but also to choose the library as a meeting point.

A spectacular but impractical building

When asked about the project, Ondrej Zemanek, of the studio of Vlado Milunic and architect of the famous Dancing House in Prague, smiles and takes a deep breath. 'Everyone asks me that. I don’t like the project, but as an architect, that’s not an argument.' This young man, trained at the Bauhaus University in Weimar, is surrounded by dozens of ultramodern architect’s models placed on tables, hung from walls and even nailed to the ceiling. He doesn’t seem like the kind of person who would be scared off by the colours and shapes of Kaplicky’s project.

When asked about the project, Ondrej Zemanek, of the studio of Vlado Milunic and architect of the famous Dancing House in Prague, smiles and takes a deep breath. 'Everyone asks me that. I don’t like the project, but as an architect, that’s not an argument.' This young man, trained at the Bauhaus University in Weimar, is surrounded by dozens of ultramodern architect’s models placed on tables, hung from walls and even nailed to the ceiling. He doesn’t seem like the kind of person who would be scared off by the colours and shapes of Kaplicky’s project.

With the creation of the curved Dancing House, Zemanek’s boss, Milunic, who also entered the competition for the National Library commission, began an architectural revolution in his country. The double-towered building, evocative of a pair of dancers, appears to move sensually towards the shores of the river Moldava. Zemanek recalls how 'the first time Milunic went to the factory to order the pieces for the Dancing House, they threw him out rather rudely' because they didn’t know how to make them.

With the creation of the curved Dancing House, Zemanek’s boss, Milunic, who also entered the competition for the National Library commission, began an architectural revolution in his country. The double-towered building, evocative of a pair of dancers, appears to move sensually towards the shores of the river Moldava. Zemanek recalls how 'the first time Milunic went to the factory to order the pieces for the Dancing House, they threw him out rather rudely' because they didn’t know how to make them.

On the subject of the Czech National Library, which will be three times higher than neighbouring buildings, Zemanek argues that it doesn’t have enough of a 'relationship with its surroundings', and that it will not be characterised by its functionality. 'It won’t have good public transport links and, before leaving home, the reader will have to think about which century the book he’s looking for comes from', since part of the Library’s collection will remain in the Clementinum, a splendid former Jesuit college where the Library is currently housed.

The Olympics: regeneration?

In spite of his views on the project, Zemanek agrees with Kaplicky’s view that the Czech Republic is a conservative country when it comes to architecture. Perhaps it is the result of the desire for stability following the upheaval that accompanied the end of communism, but Zemanek doesn’t understand this phenomenon. He doesn’t think it’s logical, when at the same time people are obsessed with anything new, from fashion to the latest mobile phones.

'Architecture should go hand in hand with the culture, society and technology of the time,' he argues, maintaining that it is absurd to build the kind of buildings that were built in the past. Vladka Rosolova, who works as an architect in Pilsen agrees, saying that 'people don’t know how to deal with new architecture' because they are used to a different kind of landscape.

In this context, Prague’s recent bid to host the 2016 Olympics is seen as the stimulus that will help to regenerate the city. Zemanek and Rosolova, however, are critical. 'I don’t think we’re prepared,' they have said, concerned that the infrastructure for the event will be built hastily and, as a result, badly. 'The Games should be something different, special, typical of the Czech Republic; something the whole world will remember.' This, they conclude, will take some time.

Translated from A Praga se le atraganta el futuro