The future is death metal-inspired art in Kosovo

Published on

Contemporary art is just one bright face of the Kosovo prism, from which the works of the likes of 29-year-old visual artist Artan Balaj refract

A few days before independence was unilaterally declared in Kosovo on 17 February, the ‘Exception/ contemporary art scene from Pristina’ exhibition was cancelled in Belgrade after an ‘organised group of Serb nationalists attacked Kontekst gallery,’ according to an official press release.

Sweden’s Malmö Art Academy was one of the first to lend their support in an ensuing petition to the Belgrade authorities. During the short-lived opening, Getty Images captured ‘a visitor walking by a work by Artan Balaj' - one of eleven young ethnic Kosovar Albanian artists participating, who works with 'multimedia' - everything from paper, acrylic, canvas, felts, ink, pastel, collage to photography.

KKK

The three red letters on the acrylic on canvas are a famous acronym of the white racist secret organisations of the US. But Krijuesit Kontemporan te Kosoves ('contemporary artists of Kosovo') is Balaj’s response to how the visual art scene in Kosovo shifted its deadlock and opened up to everyone. ‘From the seventies up until a couple of years after the war, the visual artists association in Kosovo were like an elite clan,' says the goateed, shaven-headed artist. It was curator Mehmet Behluli, a lecturer at the academy of fine arts in Pristina, who allowed students to enter works in a ‘portraits’ exhibition at the National Gallery in 2000. 'It was a scandal back then,’ remembers the 29-year-old, whose paintings and photography take their titles from songs by bands including Pink Floyd ('the best band in the world!' Balaj grins), Type O Negative and Aerosmith.

The three red letters on the acrylic on canvas are a famous acronym of the white racist secret organisations of the US. But Krijuesit Kontemporan te Kosoves ('contemporary artists of Kosovo') is Balaj’s response to how the visual art scene in Kosovo shifted its deadlock and opened up to everyone. ‘From the seventies up until a couple of years after the war, the visual artists association in Kosovo were like an elite clan,' says the goateed, shaven-headed artist. It was curator Mehmet Behluli, a lecturer at the academy of fine arts in Pristina, who allowed students to enter works in a ‘portraits’ exhibition at the National Gallery in 2000. 'It was a scandal back then,’ remembers the 29-year-old, whose paintings and photography take their titles from songs by bands including Pink Floyd ('the best band in the world!' Balaj grins), Type O Negative and Aerosmith.

'From the seventies up until a couple of years after the war, the visual artists association in Kosovo were like an elite clan'

‘Visual art in Kosovo in the last two decades is far more advanced compared to literature for example, and is distinguished with the contemporary trends,' judges Fahredin Shehu, 36, an author, poet and calligrapher in Pristina. Balaj, whose father worked as a painter in the National Theatre, came to attention in 2005 when he was named 'distinguished young artist' at the international biennale of contemporary arts in Arad, Romania in 2005. ‘He took on a local art critic who stated that no one is an artist until they are forty or fifty,’ American video artist Colette Copeland blogged at the time. ‘Balaj proved the critic wrong. His aggressive mark making metaphorically reference his experiences in war-torn Kosovo.’

War and Pink Floyd

Couple war with metal, and you nail Balaj's influences on the head. By fifteen he was playing in the first Albanian death metal band Demogorgon (‘Devil’), which he says 'was not only about the devil but politics.' The six-piece’s concerts took place in private house parties and the Theatre Dodona as ‘there was no other place to play.’ As Albanians started to lose their jobs, their children were 'kicked out from secondary school,' Balaj continues. 'We walked illegally five or six kilometres to the other part of Pristina to study in private houses, avoiding the police who would beat us.’

Whilst one million Kosovars fled then-dictator Slobodan Milosevic's regime to refugees camps in Macedonia, Balaj ‘ran away’ from military service in Croatia, finding refuge in Poland, where his KFOR translator mother comes from. ‘I didn’t want to leave Kosovo. I was fifteen, I had a big group of friends into heavy metal.’ He found the eighteen months that he spent later living in Stuttgart 'difficult' because 'I was Albanian,' he says in German. ‘And it’s still very complicated to live even here in Kosovo,’ he tells me in November 2007, in a Kosovo which is still a UN-administered province of Serbia after international forces took over after the 1999 war. ‘It doesn’t matter if you are a good artist or not,' he says, as we drink macchiatos in our first meeting at Traffic Café, a dark urban hangout in the centre of the city. 'People who want to buy my art can’t.’

Baby contemporary steps

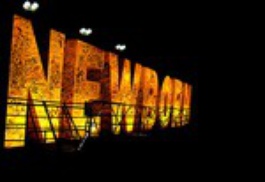

‘His tendency to climb into the level of spiritual (dark, goth) symbolism is a reflection of the revolt that he is still shaping,' says Shehu. 'A tiny minority of these artists may really shake the cemented limits of the past generations.’ With a new Kosovo in transition, it looks like Balaj has the canvas. On the historical night of independence, he was in the Illyrian Room bar, down town in the capital. 'We were waiting for prime minister Hashim Thaci to say the words that everybody was waiting for. 'It felt like a dream. Nobody can describe that feeling, ‘it's impossible. Everything is brand new.’ Like ‘NEW BORN’, the three-metre high yellow sculpture of big letters made out of metal sheets, which was unveiled outside a central shopping centre on independence day. Creator Fisnik Ismajli, director of advertising agency Ogilvy-Kosovo, is a friend of his.

With an impending appearance in the Biennale in Puglia slotted for May, Balaj is currently working on a documentary to be released this summer about the independence of Kosovo by Spanish film director Diego Hurtado De Mendoza, produced by Italian production company Fabrica Cinema. ‘Everything is starting from the beginning, so one step at a time,’ says the man who gives a 'special thanks' to 'heavy metal, punk, alternative, hippie and trans movements' in his 'Others' exhibition catalogue - what he is convinced is part of the subculture in Kosovo today. In the meanwhile, he fumbles through his diary, his hands adorned with big rings, to avoid misquoting American video artist pioneer, Bill Viola: art has to be part of everyday life, it just has to be.

With an impending appearance in the Biennale in Puglia slotted for May, Balaj is currently working on a documentary to be released this summer about the independence of Kosovo by Spanish film director Diego Hurtado De Mendoza, produced by Italian production company Fabrica Cinema. ‘Everything is starting from the beginning, so one step at a time,’ says the man who gives a 'special thanks' to 'heavy metal, punk, alternative, hippie and trans movements' in his 'Others' exhibition catalogue - what he is convinced is part of the subculture in Kosovo today. In the meanwhile, he fumbles through his diary, his hands adorned with big rings, to avoid misquoting American video artist pioneer, Bill Viola: art has to be part of everyday life, it just has to be.

Many thanks to Vera, Paulina Sypniewska and Flora Loshi