'The Constitution in Verse': Brussels 'city poets' slam EU

Published on

Translation by:

Sarah Truesdale'So the European Union doesn’t have a political constitution? Let’s at least give it a poetic one!' 50 authors have spent months putting the finishing touches to new articles in the form of alternative and critical citizens’ verse. Close-up on an initiative from Brussels which began in January 2008

In discussions which have nothing to do with politicians, reply in verse. Peter Vermeersch, poet and professor of political science at Belgium’s university of Leuven and David Van Reybrouck, both members of the Brussels poetry collective, are passionate about the relationship between politics and linguistics. After the failure of the project which would have launched the European constitution in 2004, they had the idea of a collective adventure where writing and poetry could allow citizens to ‘reconquer Europe’. They could even rewrite the constitution - in the form of verse.

27

They searched for other authors from diverse backgrounds. The original idea was to bring together 27 contributors, one per member state, but it didn’t take long for them to decide to call upon authors outside the EU. Afghani, Turkish, even Zimbabwean authors, and authors of the Shahrazad Stories for Life association - a European project which allows authors throughout the world who have been deprived of their freedom of expression to write again - have joined the team, which is a mixture of both experienced and novice writers.

Afghani, Turkish, even Zimbabwean authors have joined the team, which is a mixture of both experienced and novice writers

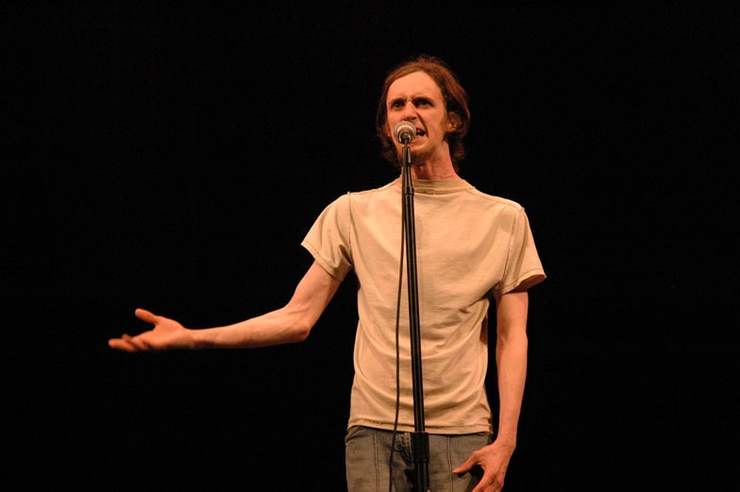

Alongside Seamus Heaney, an Irish writer who won the Nobel prize for literature in 1995, you can also find ‘new voices’ like 20-year-old Bulgarian Ekaterina Karabasheva. Some members are journalists, others translators, writers, professors or even playwrights and slammers. Like Manza, originally from Morocco but who lives in Brussels, who is one of the four making up the collective for the 2008-2009 period. He wrote article 2, and here is an extract, a rather modest translation from the French:

‘Let it move, let it cry, let it dance, let it sing, let it campaign, let it challenge, let it live, let it declare, let it pollinate, let it illuminate on sleepless nights where nothing is lost and everything is gained, taking shape as if by pure fact, dense envies.’

‘Collective dreams and doubts’

These authors share the belief that poetry can play an important role in society and beyond. It’s about re-energising European democracy. ‘What poetry can bring is imagination, imagination well and truly,’ says Peter Vermeersch. ‘The European union must listen to poets and authors more, who are ambassadors of society,’ says Romani co-author Hedina Tahirovic Sijercic, a former journalist in eighties Serbia before she immigrated to Canada and then Germany. ‘Politicians must read more of the work of poets and writers, who are truly ambassadors of the people.’ ‘If poetry can’t change everything in a depoliticised world, it can at least allow us to bring back important political subjects which are at the heart of public debate,’ adds José Ovejero, from Spain.

These authors share the belief that poetry can play an important role in society and beyond. It’s about re-energising European democracy. ‘What poetry can bring is imagination, imagination well and truly,’ says Peter Vermeersch. ‘The European union must listen to poets and authors more, who are ambassadors of society,’ says Romani co-author Hedina Tahirovic Sijercic, a former journalist in eighties Serbia before she immigrated to Canada and then Germany. ‘Politicians must read more of the work of poets and writers, who are truly ambassadors of the people.’ ‘If poetry can’t change everything in a depoliticised world, it can at least allow us to bring back important political subjects which are at the heart of public debate,’ adds José Ovejero, from Spain.

This constitution is like all others: it is composed of a preamble (‘Let us not dip our brushes in an inkwell of indecencies’), principles, then fundamental rights, declarations, fundamental politics, the European anthem and final clauses. Then there are serious articles on immigration or democracy, or crazy pieces like the ‘law of foolishness’ or even the ‘law of fairytales’. Funny, serious and melancholic, they illustrate the ideal citizen and form a cultural appeal for a closer and more citizen-friendly Europe.

The Constitution in Verse, Publication Passa Porte, 2009

Translated from La constitution européenne, on peut aussi la « slamer »