The Case of the Missing Foreskin

Published on

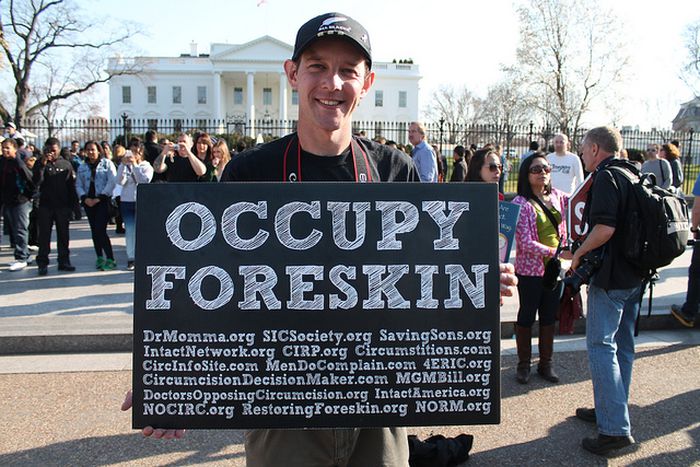

Earlier this year Norway's health minister sparked a nationwide squabble by proposing that infant circumcision should be freely available on national health providers. It's not the first such controversy: just two years ago Germany witnessed a similar debate, while protests regularly flare up around the whole of Europe. But just why is circumcision so controversial?

Riotous public debates are often sparked by little things, but it seems surprising that a shred of skin no longer than a few centimetres can prove to be so controversial. But if you ask Ferhad*, male circumcision shouldn’t be a topic of public debate at all.“To be honest, it is not something you would remember. It is more like one day you wake up and it is gone.” Born in Sweden to Kurdish-Iranian parents, he was circumcised at the age of four, in accordance with the Muslim custom. When he was younger, he never thought about his missing foreskin. As he rightly observes, “if you are circumcised, you don’t dwell on it all the time, simply because you don’t know anything else.” However, Ferhad is frequently reminded that being circumcised is not the norm in Europe. It starts with casual comparisons in the changing stall after sports classes in school, but in extreme cases, the case of the missing foreskin can lead you straight into a legal court.

In April this year, the Norwegian conservative government of Erna Solberg presented a white paper proposing to make male circumcision available on the national health service. While the team behind Bent Høie, the Norwegian health minister, argued that performing the surgery at public hospitals would make the procedure safer, their proposal provoked a public outcry. As early as 2012, Dr. Anne Lindboe, Norway’s children’s rights ombudsman, had repeatedly ask for a ban of circumcision, classifying it as an unnecessary practice that disregarded a child’s right to bodily integrity. No parent, Lindboe argued, should be allowed to make unilateral and irrevocable decisions about the looks of their child’s body. What seemed like a small cut for a man suddenly split an allegedly secular model society into opposing camps. In June, the Norwegian parliament accepted a bill to protect the right of religious parents to have their sons circumcised by either a surgeon or a “circumciser” from their religious community.

In April this year, the Norwegian conservative government of Erna Solberg presented a white paper proposing to make male circumcision available on the national health service. While the team behind Bent Høie, the Norwegian health minister, argued that performing the surgery at public hospitals would make the procedure safer, their proposal provoked a public outcry. As early as 2012, Dr. Anne Lindboe, Norway’s children’s rights ombudsman, had repeatedly ask for a ban of circumcision, classifying it as an unnecessary practice that disregarded a child’s right to bodily integrity. No parent, Lindboe argued, should be allowed to make unilateral and irrevocable decisions about the looks of their child’s body. What seemed like a small cut for a man suddenly split an allegedly secular model society into opposing camps. In June, the Norwegian parliament accepted a bill to protect the right of religious parents to have their sons circumcised by either a surgeon or a “circumciser” from their religious community.

Religious practice or bodily harm?

Although Jonathan’s* father isn’t particularly Jewish, he still had his son circumcised eight days after his birth. “My Dad thought it would be weird for me and my brother if we saw we were different to him, so he went through with the procedure.” But Jonathan, who was born in England, soon realised that he looked different than other boys: “I remember discussing it in the toilet at kindergarten when I was three. I saw the other kids had a foreskin and tried to tell them that thing was weird and probably shouldn’t be there!” Twenty years later, Jonathan is not entirely sure about the moral implications of ritual circumcision. Although he has never met anyone who regretted being circumcised, it now seems wrong to him as a matter of principle. “If circumcision is considered an important part of a certain culture, than a guy should decide for himself and opt in, getting circumcised as an adult, rather than opting in on behalf of his children.”

In June 2012, Germany witnessed a debate similar to Norway’s after a court ruling in Cologne equated male circumcision with bodily harm. This led to a lot of hospitals around the country ceasing to perform the procedure, whose legal status was suddenly deemed to be “uncertain”. With a sizeable Turkish and Kurdish population of approximately four million, which routinely performs ritual circumcision on all boys, this was no minor disturbance. Although the court in Cologne did not ban the practice altogether, it still ruled that a child’s right to bodily integrity should override religious and parental stipulations. After heated discussions about the necessity of a foreskin in the 21st century, the German Ethics Council stepped in and called for universal legal standards, thereby rejecting the claim that male circumcision is a harmful practice. In December 2012, the German parliament hastily approved a law that ensured that male circumcision stayed legal, if performed by a trained doctor or circumciser, who is allowed to make the cut up until six months after the birth of a boy.

In June 2012, Germany witnessed a debate similar to Norway’s after a court ruling in Cologne equated male circumcision with bodily harm. This led to a lot of hospitals around the country ceasing to perform the procedure, whose legal status was suddenly deemed to be “uncertain”. With a sizeable Turkish and Kurdish population of approximately four million, which routinely performs ritual circumcision on all boys, this was no minor disturbance. Although the court in Cologne did not ban the practice altogether, it still ruled that a child’s right to bodily integrity should override religious and parental stipulations. After heated discussions about the necessity of a foreskin in the 21st century, the German Ethics Council stepped in and called for universal legal standards, thereby rejecting the claim that male circumcision is a harmful practice. In December 2012, the German parliament hastily approved a law that ensured that male circumcision stayed legal, if performed by a trained doctor or circumciser, who is allowed to make the cut up until six months after the birth of a boy.

A minor surgical procedure that remains exotic nonetheless

Most of the time, male circumcision isn’t given that much attention in Europe, where female genital mutilation (FGM) – sometimes wrongly termed “female circumcision” – is a far more prevalent preoccupation. But the two practices should in no case be confused. FGM is just what its name suggests: a gruesome act of violence against women which is outlawed in all European countries and rightly so. Male circumcision, however, is an entirely different story. If carried out correctly, it is only a minor surgical procedure, which rarely has any negative effects on a boy’s physical or mental well-being. According to the World Health Organisation (WHO) report Male Circumcision: Global Trends and Determinants of Prevalence, Safety and Acceptability, around 30% of all males were estimated to be circumcised in 2007, of which 69% were Muslim and 0.8% Jewish. The remaining 13% belong to neither of the two religions, but were circumcised because the practice was encouraged up until the 1970s in America, Canada, the UK and Australia, for the sake of disease prevention and hygiene.

Most of the time, male circumcision isn’t given that much attention in Europe, where female genital mutilation (FGM) – sometimes wrongly termed “female circumcision” – is a far more prevalent preoccupation. But the two practices should in no case be confused. FGM is just what its name suggests: a gruesome act of violence against women which is outlawed in all European countries and rightly so. Male circumcision, however, is an entirely different story. If carried out correctly, it is only a minor surgical procedure, which rarely has any negative effects on a boy’s physical or mental well-being. According to the World Health Organisation (WHO) report Male Circumcision: Global Trends and Determinants of Prevalence, Safety and Acceptability, around 30% of all males were estimated to be circumcised in 2007, of which 69% were Muslim and 0.8% Jewish. The remaining 13% belong to neither of the two religions, but were circumcised because the practice was encouraged up until the 1970s in America, Canada, the UK and Australia, for the sake of disease prevention and hygiene.

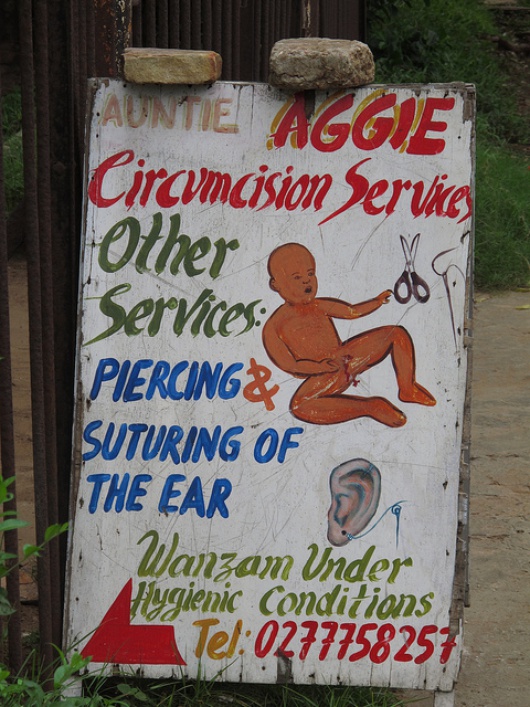

In Europe male circumcision never really caught on. With the exception of Bosnia and Herzegovina, Serbia, Montenegro, Kosovo, Macedonia and Albania, circumcision rates in European countries mostly lie well below 10%, according to WHO estimates. But with a growing influx of immigrants from Muslim countries, these figures might have to be revised within a few decades. “If you ask me, circumcision is seen as way too exotic in Europe,” says Ferhad, whose only concern with his missing foreskin is that “sometimes girls don’t really know what to do.” But he is far from being alone with that. Other than for religious reasons, circumcision can help to tackle medical conditions like chronic urinary tract infections or pathological phimosis. The latter is a condition in which the foreskin cannot be fully retracted, which can be extremely painful and result in all kinds of complications.

The perks of having no foreskin

In the UK, where circumcision is not available on the National Health Service (NHS), around 6% of all men are reported to be circumcised for non-religious reasons. Paul* was diagnosed with phimosis when he was 12: “I remember the surgery. It was very painful and I couldn’t walk properly for a month. They put stitches around it and I had to take warm baths for the pain.” After a few months, the physical aftermath of the surgery had abated, but a few small psychological effects remained: “I knew being circumcised was unusual in the UK, so I was worried that girls might think me strange. But I still liked being circumcised because before you would have to peel the foreskin back and clean underneath, which was gross.”

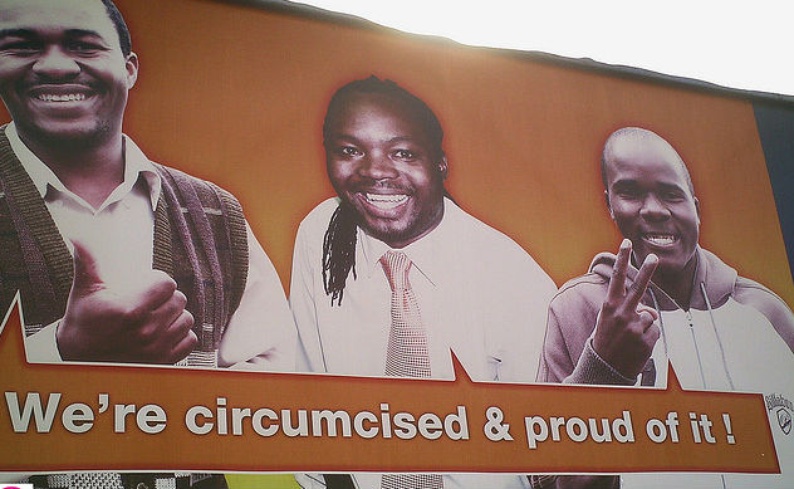

In recent years, the WHO has taken the circumcision debate one step further. According to some medical studies, circumcised men are at a lower risk of contracting HIV and other sexually transmitted diseases. This is why the WHO, together with UNAIDS, have repeatedly called for male circumcision to be included in comprehensive HIV prevention programmes in sub-Saharan Africa. While in some countries, like Ethiopia and Madagascar, male circumcision is already a widespread practice, figures are now rising in other African countries. In Europe, where circumcision is not pushed as an AIDS prevention scheme, no remarkable changes have been detected over the last 50 years, whereas circumcision rates in the US, Canada and the UK have been slowly falling. The main reasons for this could be more recent medical studies which were less conclusive about the health benefits generally credited to circumcision, as well as many national health services not covering the cost of the surgery any more.

In recent years, the WHO has taken the circumcision debate one step further. According to some medical studies, circumcised men are at a lower risk of contracting HIV and other sexually transmitted diseases. This is why the WHO, together with UNAIDS, have repeatedly called for male circumcision to be included in comprehensive HIV prevention programmes in sub-Saharan Africa. While in some countries, like Ethiopia and Madagascar, male circumcision is already a widespread practice, figures are now rising in other African countries. In Europe, where circumcision is not pushed as an AIDS prevention scheme, no remarkable changes have been detected over the last 50 years, whereas circumcision rates in the US, Canada and the UK have been slowly falling. The main reasons for this could be more recent medical studies which were less conclusive about the health benefits generally credited to circumcision, as well as many national health services not covering the cost of the surgery any more.

If you ask Paul, he wouldn’t think twice about being circumcised again: “In my opinion, the foreskin is a glitch in evolution that can be solved with a simple operation. If I had a boy, I would want him to be circumcised because I really think it’s worth it.” Jonathan, on the other hand, wouldn’t want to make the decision: “If I had a little boy I would probably not want him to be circumcised because it’s his foreskin and he should decide if he keeps it or not.” Ferhad, however, can’t imagine having a kid and not having him circumcised, even though he’s not a practising Muslim: “When I was in high school, the boys would talk about a lot of disgusting things that I couldn’t relate to”, Ferhad explains. “I think that had to do with me being circumcised, which is why I am quite happy to have turned out this way”, he adds with a laugh. Maybe something to bear in mind? After all, it is only a small cut for a man.

* All names changed by the author.

This article was first published in the October issue of Europe&Me. All rights lie with the author and Europe&Me.