The Best Weapon to Fight Terror? A Constitution

Published on

After the Madrid bombings, the European Union pledged greater co-operation between its police and intelligence services. Will this renewed commitment infringe upon or bolster Europe's democratic principles?

In the light of the recent terrorist attacks in Spain, security has become a priority for European Union member states. In what can be considered a revival of political conscience, the day after Madrid's deadly blasts people took to the streets where, according to some estimates, a quarter of the country's population stood united against terrorism. But with growing demand for more security comes concern over whether anti-terrorism policies can be reconciled with the fundamental tenets of freedom and justice.

In the light of the recent terrorist attacks in Spain, security has become a priority for European Union member states. In what can be considered a revival of political conscience, the day after Madrid's deadly blasts people took to the streets where, according to some estimates, a quarter of the country's population stood united against terrorism. But with growing demand for more security comes concern over whether anti-terrorism policies can be reconciled with the fundamental tenets of freedom and justice.

A united response

Based on their public response to terrorism, we can assume Europeans support the EU’s shared democratic purpose. But beyond this façade scepticism prevails. Public opinion polls show that a majority of Europe's citizens still do not identify with the EU. This deficit in “Euro-patriotism” is problematic when contrasted to the body's quest for a common security strategy. Effective security can only be provided with common agreements between countries on what needs to be protected. Today, problems facing the EU are as diverse as the security policies of each of its member states. Although critics argue that traditional nation states no longer exist, they still do when it comes to security and intelligence gathering. These deep-rooted national practices are hampering chances for greater co-operation between national intelligence services.

New and old Europe: One policy

But the more countries involved, the slower the policy-making process will be. It is also not clear whether, despite working together, the policy preferences of new member states match those of “old Europe.” Already some countries are pushing for “differentiated integration” or, as the British dismissively call it, “multi-speed Europe,” and it remains uncertain if a two-speed Europe can effectively fight terrorism and organised crime.

Whether the post-communist states will work effectively against crime is debatable. Their interests have been to maintain good economic ties with their eastern neighbours. But now this interest could be jeopardised. Hence, their reluctance to impose tighter border controls with their traditional trading partners is understandable. Concerns about the implications of an enlarged Europe are manifold. Europol has warned that Accession States will offer opportunities for transit of resources and destinations for criminal goods and services. Major investments by illegal funds are predicted and criminal organisations are likely to relocate their activities to these countries. Discussions amongst EU states are common when policies need to be defined. More than the geo-political issues of enlargement, the greatest challenge will be to find a shared understanding of the terrorist threats facing Europe. With the spectre of the failed humanitarian missions in the former Yugoslavia in the 1990s, it is obvious that European co-operation still has a long way to go. International politics torn by disagreement are no foundation to form a new partnership. However, working together against a common threat should convince European leaders of the benefits of joint action. This is certainly not the time for opting out.

Security and Democracy

It is only recently that Europe's governments agreed to co-operate on intelligence matters. Looking at how international crime has been tackled in the past, trust (or the lack of it) amongst intelligence agencies will be a lasting issue. Will the EU effectively fight terrorism and improve security by implementing basic measures like strengthening border patrols in new EU states? Studies show that with its current police force Poland would not be able to implement the Schengen agreement that regulates the circulation of people across Europe.

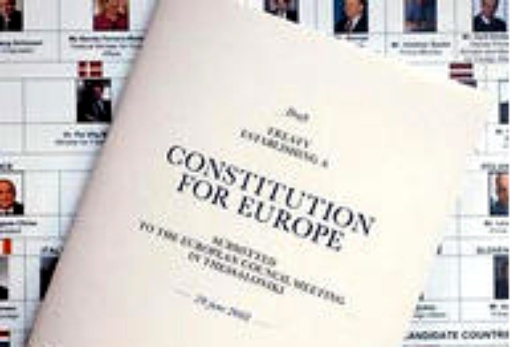

Greater co-operation will only be possible if backed by shared democratic values. Therefore, inscribing these values in a European Constitution would be an effective first step in putting together a common security policy. Whether current politics and the new order of international relations will foster a common European security policy remains uncertain.

Defining common values

Although better co-operation is desirable, human rights groups have expressed their concern about the effects of stricter security on civil liberties. The European public should not forget the small print when signing up to a contract on increased protection. An “ever closer union” between the peoples of Europe might not be a utopian idea after all. Last year huge numbers of people demonstrated against the war in Iraq in London and across Europe. Proof of such political activism defies common associations with Britons as “couch potatoes” and a-political. However, Europeans need to move from their responsive approach to political culture to a more proactive stance. Negative press on European integration has not helped the

cause. Stirring up patriotic sentiment seems a common method of British tabloid papers. The challenge is to reform Europe and European citizenship constructively. Only in this way can Europeans feel secure in their identity and fight new insecurities. Public mobilisation through the media can help that cause. Support for European integration has been lukewarm in prospective member states. Europe needs to counter this scepticism by building a union based on solidarity and stability. There is hope that the draft of the future European Constitution can reinforce European solidarity in its pursuit of a common destiny.